We have a “last mile” problem in patient communities.

In the first post of this series, I asked for general advice about finding your people — the peers who could give you advice about your health condition and answer even your most secret questions.

Now I’d like to focus on how someone would approach getting advice about a specific procedure: brain surgery to remove a meningioma, the most common type of brain tumor.

I started by looking at the blog of someone I know: Charlie Blotner, who blogs and helps run the Brain Tumor Social Media (#btsm) community on Twitter.

Charlie lists an array of resources, including the National Brain Tumor Society. Clicking through, I found a page listing every known type of brain tumor, including meningiomas. The first-person stories on their site about meningioma are intriguing, but lead nowhere. You never find out what happened to anyone who shares their story — unless the person died from not treating it. Yikes.

I also followed Charlie’s links to other blogs, but I fell into one of the pitfalls of reading people’s personal accounts of illness: It was interesting, but not helpful to me. People blog about what they want to share — a gift to the world, make no mistake — but their stories often aren’t organized in a way that makes it easy for a newly diagnosed patient to find what they need, to answer the questions that keep them up at night.

Questions like:

- What were the main reasons why you chose surgery over other options?

- How did you prepare for brain surgery, both physically and emotionally? What was the scariest part?

- How did you talk with friends and family about your diagnosis? Did it change how they treated you?

- Post-surgery, what helped you get better faster? If you had setbacks, why? If you could do it over again, what would you have skipped or done differently? How long did you really feel like crap?

- Are there any hidden upsides to brain surgery? Besides survival, obviously.

When I asked directly for advice, via email, Charlie advised me to check out Eric Galvez’s blog about his experience with a meningioma. Indeed, it would be a perfect read for another athletic young guy like Eric, a licensed physical therapist and surfer…but how would a newly diagnosed person find his blog if they didn’t have the phone-a-friend network that I do?

Liz Salmi’s blog, The Liz Army, is visually appealing (she is, after all, a graphic designer) and she tags her posts in a very helpful way: Newly Diagnosed; On Treatment; Advocacy; etc. It’s on her site that I started to find the practical tips I was looking for about preparation for and recovery from brain surgery. And I found an answer to one of the toughest questions I was asking: Are there any hidden upsides? Steven Keating, featured along with Liz in The Open Patient, said that when he forgets something he gets to claim, with a laugh, that they must have cut that part out of his brain.

Charlie also pointed me to Samira Rajabi’s philosophical meditations on brain surgery that anyone might benefit from, such as her essay, “Radical Honesty: Surviving Treatment, Recovery and Getting Better.” And if you know anyone who has been diagnosed with a vestibular schwannoma, aka an acoustic neuroma, please point them to her enlightening and useful blog.

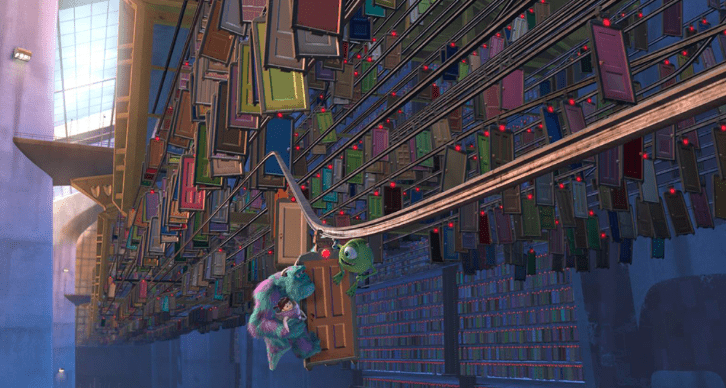

But again, it isn’t efficient to rely on word of mouth to connect the need-knower (someone searching for a peer) with a problem-solver (Eric, Liz, Samira). When I Googled vestibular schwannoma, for example, no patient-written blogs appear on the first 10 pages of results. If you add the word “blog” to the search however, it’s like that scene in Monsters Inc. when a seemingly endless line of doors appear, each one leading into someone’s intimate story.

It’s miraculous. And yet invisible to most people.

Charlie also recommended an old-school list serv focused on oligodendroglioma (say THAT three times fast). I have to quote Charlie in full so you can benefit from their full blast of wisdom and experience:

“I’m a big fan of crowd sourcing information, so I did just that. Even though I read textbook chapters and journal articles to find out more about the best treatment option, center, and doctors, this list serv was my primary source of information. High school me hated biology class, so I needed to talk to people who knew more about the brain and were willing to share.

I found out that MD Anderson had a proton beam radiation machine from the list serv (my first choice of a treatment protocol that fell through when my tumor was too deeply imbedded for what they wanted to do), that I needed to see Dr. Berger at UCSF if I wanted to wake up still talking, and who to avoid based off of who had negative outcomes with particular surgeons after having similar tumors removed from similar areas of the brain.”

If you have searched online for answers to questions like the ones in the list above, how did you do it?

If you have ideas for how to solve the “last mile” problem, please share those, too.

Next case study: One in a million diagnosis

Featured image: Brains, by Neil Conway on Flickr

This is a great post to demonstrate why blogs are often not the best place to find reliable, current and usable information to make informed decisions. This is why ACOR and Smart Patients were/are in the business of fostering communities where verbal communication between peers is key. Blogs are more like a megaphone for a single voice, while online communities, when properly managed, bring multi-tiered responses to what is often highly individual questions.

Yes! But for the person just starting out, not aware yet of communities, not sure they want to join a community — how do we reach and help them?

And a friend just tweeted in reply to my question: “Facebook groups, Facebook groups, Facebook groups.” Meaning, I think: fish where the fish are.

In 2014 I wrote “Save us, Facebook” about how FB should acknowledge its role as a de facto health platform.

Key points from that post:

People rely on trained professionals to diagnose and treat their conditions, but they crowd-source the questions that spur clinicians to operate at the top of their training.

Access to each other supercharges access to information.

I’m not a fan of Facebook as a health platform. The company’s shifting policies on anonymity and privacy controls sow confusion and distrust. Facebook is also not set up to track health data or even to effectively archive discussions.

There are other health community platforms (including ACOR, Smart Patients, Inspire, PatientsLikeMe…) But none of them have Facebook’s reach.

UPDATE:

An experienced FB group user tweeted the following:

“Upsides: can ask questions and have convos, can join groups for different symptoms, MANY people participating (basically crowdsourcing). Downsides: particularly in bigger open groups, misinformation can be rampant– smaller closed groups are better, but harder to find. Also, overall, disease severity and coping mechanisms aren’t representative– people with more severe dz and trouble coping comment more. Other upsides: is suuuper easy to form friendships– just friend them on fb. Also groups for diff life stages (young adult, caregiver, etc.)”

“”Downsides: Also, overall, disease severity and coping mechanisms aren’t representative– people with more severe dz and trouble coping comment more. ”

I have never seen this as a downside but as a totally natural fact of online and IRL communities. People who have less of a disease burden will, in all likelihood, discuss their disease a lot less than those for whom surviving is a constant effort.

FB is the de facto platform. No doubt about it. If you want to have far reach there is nothing else like it. It doesn’t mean you’ll create there the best community possible. It only means there is no competition for its reach.

For some reach is the most important factor. Take for example the remarkable work that Corrie Painter is doing right now to recruit research participants for the first large angiosarcoma research project ever undertaken. A core element of this project is to reach as many people with this highly deadly and rare type of cancer. FB is simply irreplaceable for this purpose.

I have found online brain tumor/nurosurgery support groups to be full of hostility towards MDs, and to be populated by incurious people eager to blame someone for their problems. Doctors are frequently accused of dishonesty (in fact they do not have all the answers). Surgeons are frequently accused of incompetence because it turns out that brain surgery is pretty unpleasant afterwards. I would tend to stay away.

In 1993, when first Dx with “fibromyalgia,” I sent $99 to an outfit in San Francisco that printed out reams of medical journal articles and mailed them to me.

Later I used the Net to research directly, find associations and patient threads to share experiences with various supplements etc., and find highly recommended alternative/integrative physicians, as health plan PCP and specialists only offered a list of Rx not really working for me.

Then social media blossomed, with blogs, groups, FB, Twitter, chats, remote attendance at conferences etc., and crowdsourcing, much easier to discover and share patient experiences, functional MD and biologic dentist resources, and found out what the real underlying causes were for me.

Great to be healthy again, active and vital again, and Rx free!

Wise to fish where the fish are. Learn to fish… Done right, yields loaves and fishes, with benefits to many.

Susannah,

First… I hope you (or the person for whom you are advocating) is strong, comfortable and supported. That whatever is next on your plate, you feel well informed and confident in the choices you are making and the actions you are taking.

Second, I had a very similar experience when I was newly diagnosed. I went online to learn more about what was wrong with me and what I should do. My search results fell into two buckets: scholarly stuff (that I usually had to pay to access and have friends interpret) or personal narratives (that all too often reflected my own state of being, namely newly-diagnosed and scared).

What was missing was a third bucket: the expert stuff…the been-there-done-that narrative of patients with similar diagnoses but further down the path than I was. This was in 2010 and the internet still felt new and not particularly navigable. Seven years later, thanks to you (and Dave, Gilles, Regina, SPM, Larry, Sarah…so many!), the idea of patient engagement and the notion that patients can share not only experience but expertise has been normalized.

Yet…there’s still work to do.

When the stark reality of a scary diagnosis confronts us, where do we turn? Expert patients are still hard to find (at least in my experience) because, once you get “better,” you really want to put the experience behind you and move on. To this day, I refuse the label “patient.” I am ashamed to say that I do not blog on my condition though I could paint a very, very optimistic picture for those newly diagnosed. Why? For me, I still feel guilty and ashamed (that’s hard to write, but true).

So how might we retain/re-engage expert patients (let’s ignore financial incentives for now)? Could we prompt conversations with the questions you ask? Should these conversations be organize by disease-state as well as diagnosis (that would have helped me a LOT)?

Your questions are precious…they are honest, fundamental. I think if I were recruited to serve as a patient expert, your questions, especially the last one, would work.

Wishing you/your loved one strength, courage, clarity and most of all love.

Thank you, Natasha! I did work with a friend to put together those specific questions — and your answers & insight are extremely helpful. My friend is indeed strong & supported, but she and I are curious to know if there is something ELSE she could be doing to prepare.

I wrote out answers to those questions. TL/DR:

1. Giving help is an act of love. Accepting help is an act of trust. Getting sick opened my heart to be more loving and trusting.

2. Like Abby, my husband helped me stick with a rigorous recovery. Keep moving, and count your wins!

3. Keep track of tests, labs, meds etc…because stuff can slip through the cracks.

4. Prepare for the fact that sometimes you might be right.

I’m intrigued by #4 — as in, you might be right… to worry? To go bed early? To drink that extra glass of Champagne?

Ha! Yes to all of the above!!

But what I’m actually referring to is that uncomfortable situation when you might know something or having information that your clinician does not (or does, but disagrees with you). For example, that you’ve already had a CT scan. Or that FNAs are not diagnostic for Hodgkins. Or that the patient is on peritoneal dialysis at home so please double check before sending him down for hemodialysis.

It’s unnerving to discover that even in our vulnerable condition, we sometimes know things that must be must be brought forth.

When I had my craniotomy for a golf ball size meningioma in 2005, there was little to nothing online. When I asked my surgeon about outcomes, he pointed to a photograph of an airplane on his wall and said, “My patient is now flying his airplane.” Lol.

All I knew, going into surgery, was that it was too big for radiation, and that I had to have it out ASAP because of its school-based location, size, and threat to vital structures. I figured I would deal with the aftermath afterwards.

Afterwards, I didn’t blog about my experience because my recovery was so rough. I slept most of the time for several weeks. because my meningioma surgery required access through my ear, I lost hearing on that side and balance nerves. I had zero balance and needed therapy for that. The sudden hearing loss on one side was totally disorienting, and for a long time I could not stand being in a place with any noise at all. I couldn’t drive, I couldn’t think straight, I couldn’t remember anything for many weeks. To this day, I have a memory gap of literally years after surgery, and my short-term memory still is not nearly what it used to be.

However, my recovery was accelerated by going back to college.

Within a year after surgery I was a full-time student. The rigor of writing papers and reading and working projects was a phenomenal help to my recovery. I cannot remember most of what I learned, unfortunately, but my husband would swear that my college experience was the turning point in my brain recovery.

It’s important to note, that I could not have survived at all without my husband’s care and attention. I desperately needed him for many many months after surgery.

The balance therapy exercises were also critical in my physical recovery.

10 years after surgery, I was able to get hearing aids that pick up the sound on the deaf side. I still cannot identify where sounds are coming from, which is a real handicap, I must admit. Plus, I’m still very uncomfortable and noisy situations, and cannot have a conversation with anyone in a loud room. I find myself withdrawing and/or fleeing at the earliest possible moment. The downside of that, is that I really cannot socialize with more than one person at a time. That isolation is probably the worst thing I’ve suffered since surgery.

Thank heaven for my husband one more time. He made enough money at his job so that I did not have to work when I clearly was unable to for many many years.

I still do not work, even though I had a two-year stint as a medical assistant. I could not trust my memory to handle procedures and dosages of medications. I actually was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2015, my daughter was critically ill and died that same year, and so I resigned. I’ve had two mastectomies since then, and by golly I’m still here.

I just can’t work anymore, and at 62, I spend a lot of time fighting to save the affordable care act. I wouldn’t say that life after meniingioma surgery was great, but I’m such a strong person now, and I find many moments of joy.

Abby, you’re awesome. Thank you for the honesty about the challenges you have faced (breast cancer, too? You are stronger than most!) and how you’ve dealt with them. Honoring the importance of sleep is so important, as is the tip to get engaged intellectually, to “work out” your brain while you recover.

Again, thank you!

Thanks for the kind words, Susannah! Yes! Challenging brain engagement and exercise (I neglected to mention) were the keys to recovery for me. I walk vigorously every day (the treadmill is my friend).

All good wishes for you!

Abby…you are a portrait of resilience. Perhaps, that blog…?

Thanks, Natasha! I don’t blog about my illnesses because I’m tired of them, to be honest! I find that getting outside myself is best for me right now. I’m really fired up by our national political disaster, and choose to use my energies to fight those battles now <3

Claire Snyman shared a blog post with great advice about recovery from brain surgery:

“The brain heals in its own time.

This was my biggest lesson in my recovery, as a patient.

Make time your friend and not your enemy.

You cannot force your brain to heal quicker – it will come.. in its own time.

Take small steps, each day…and you will move forwards, even with the steps backwards.”

Thanks, Claire!

Just reading through all these posts now and really great commentary and thoughts! This is a great post Susannah – thanks so much for starting and questioning 🙂

Susy,

This is Lily Welch from PHS. Thanks for sharing this on FB. I have been recently diagnosed with breast cancer which has an enormous support community nationwide. I was inundated and overwhelmed with too much information up front for places to access free meals, support groups, art classes, children’s camps, family therapy, you name it! Unfortunately the more rare cancers and less popular common cancers suffer from offering little to no community support for their sufferers. I have also had thyroid cancer twice which is pretty common, and got basically no information from my doctors about community support.

I know you have a background in health technology and so this is a passion for you but it is a vital way that Americans connect today. I hope that people in your field will develop apps for different diseases and health issues that will list local resources and provide basic education for the stages of care. I have a friend currently working out an idea for this related to obstetrics and postpartum. Please message or call me anytime. I’m so impressed with you along many of our PHS alums helping the world!!

Lily!! So great to hear from you — thanks for commenting and sharing your experience & perspective.

(Note to everyone else: yep, I was called Susy until I found out why I was named Susannah and made the switch).

I agree — the worldwide breast cancer community is an incredible resource. I hope that other conditions can follow their playbook — at least some aspects of it.

All the best to you and your family.

Thanks for the excellent post, great to see! As you asked folks to share, I’ll just add a few questions/points that helped me through my own brain cancer experience in case they are useful for any patients. They are divided into two areas – personal and technical.

Personal:

– Ask family members or friends to accompany you to all appointments as the more ears/eyes/questions, the better. Try to find people who can be your advocate, can take notes, and help with logistics/insurance issues.

– Often your family/friends want to help, they just don’t know how and don’t know how to bring it up. If you want help, just ask them or find one person you trust and ask them to help organize your supporters and tell them what works best for you (i.e. do you want flowers/books/food, them to be with you in appointments, do you want them to help with updating other supporters, making a blog website, etc).

– Don’t fear statistics – everyone is different and you will get through this!

– Post-surgery the brain can take a while to recover, though it is incredibly flexible and full recovery often occurs. Almost all brain surgery patients I’ve talked to have had issues right after surgery (things like trouble talking, writing/spelling, using their limbs properly, headaches, sleep issues, etc). Though over time (sometimes as quickly as after a few weeks or months), these issues get better over time and often disappear.

– Enjoy the rare perspective you’ll have on what is important in life. You will make it through this, and that perspective will stick with you. Plus, think of all the cool things you might get to experience that almost no one else on the planets gets to do – things like:

– Feel someone touch and stimulate your brain if in awake-surgery (doesn’t hurt, quite an amazing sensation!).

– Explore your own skull and tumor through your MRI data. Check out 3D Slicer (https://www.slicer.org) if curious to dive into the data, you can make your own textbook images, and perhaps even 3D print your skull or tumor using http://www.Shapeways.com or another 3D printing site. Put your tumor to a better use by making it into a bottle opener or a Christmas tree ornament to give to friends!

– Be able to participate in research studies that can help save other people’s lives. Share your data/comments/thoughts online to help your supporters understand what you are going through and let other patients learn about your treatment experience.

– If you do proton radiation, you get to sit inside a particle accelerator and hit by the fastest bullets in the world – protons at over 1/3 the speed of light (over 200,000,000 MPH)! This makes you slightly radioactive after (don’t worry, not a dangerous amount for others) and it’s pretty interesting to measure yourself with a Gieger counter. And if the treatment area is near your optical nerve, they can trigger it, which results in a faint blue lightning show that you can see with your eyes closed (amazingly beautiful to see!).

– Enjoy learning from data produced from clinical scans and research studies. For instance, watching your skull heal over time, see how your mental capacity is changing over time (perhaps even getting better than before!). Try out sites like Open Humans if curious about sharing data and using applications to explore your data.

– Have the best excuse for forgetting people’s names.

Technical:

– For brain tumors, surgery is likely the most important variable. Get multiple opinions before making decisions on a surgeon/treatment route, and ideally at different hospitals/institutions. Even if you like the surgeon, always get multiple opinions.

– Find patient communities to talk with about their experiences/treatment paths/contacts and ask for introductions to experts/doctors they recommend. Often hospitals have patient groups that meet every month or more, and lots of online sources like PatientsLikeMe and Facebook groups (I noticed you covered this topic in your previous post, which was also great to read!)

– Ask about clinical trails before surgery to see if any are interesting treatment routes or if any need data pre-surgery. Check https://clinicaltrials.gov

– Before surgery, ask about potential routes for removed tumor tissue in terms of trying to grow the tumor (either in a culture dish or in mice). This can be used for testing treatments on your tumor tissue if it grows.

– Ask the doctor what they would do if in your situation. Ask for reasons why – the downsides and the benefits.

– If you have time, look at completing various research studies. It can help science, and often you can collect the data and participate again post-surgery to compare (which can potentially help you as well, though don’t participate with that expectation). Things like MRI spectroscopy scans, psychological assessment/testing, FMRI scans, etc. Ask your doctor about research studies.

– Ask for your clinical data, even if you don’t use it or even look at it. Best to have it on CDs or other formats in case you switch hospitals or want to explore it yourself.

– When participating in either research studies or clinical trials, have an advocate with you to help read through the paperwork carefully in order to understand risks. Often you can also look to online patient communities and see if others are participating or any early results. Check to see if you can access the data produced in a research study if you participate, and if you aren’t allowed, ask if it could be made available to you.

– Check out some of the recent research papers related to your tumor type. Use Google Scholar to search or find a website that summarizes research/findings for specific conditions. Often doctors/nurses or patient groups can recommend some. For me, http://www.astrocytomaoptions.com was amazing helpful. Ask your supporters if they can help look into this for you.

Thank you! Now I’m a little envious of your description of the cool stuff, like the lightning show.

Another gem of a reply (series of replies, really) on Twitter from Debi Cirasole, answering the questions above:

1. What were the main reasons why you chose surgery over other options?

The prognosis is better, with complete removal of visible tumor

2. How did you prepare for brain surgery, both physically and emotionally? What was the scariest part?

Only 3 weeks to “prepare” & wasn’t sure how to. Looking back, I wish that I had rode some carnival rides & donated my hair (instead of cutting off blood caked remainder in hotel bathroom).

3. How did you talk with friends and family about your diagnosis? Did it change how they treated you?

I didn’t talk to anyone about it initially. My diagnosis was a mess from the beginning; I was lied to & mistreated by my original “care” team. Yes, my relationships changed, but so did I.

4. Post-surgery, what helped you get better faster? If you had setbacks, why? If you could do it over again, what would you have skipped or done differently? How long did you really feel like crap?

Sleep! Sleeping was the answer to everything post crani. My setback was an incision infection, caused by my embarrassment; instead of letting my incision air out, I would bandage & cover it. That was really stupid.

I felt like crap for months… although, I also had multiple other health issues hit at the same time.

5. Are there any hidden upsides to brain surgery? Besides survival, obviously.

Besides survival? No.

I really struggled with the internet when I was newly diagnosed–all of my doctors told me to stay off google, so I did. In hindsight, I really regret that. I did not find the robust online brain tumor community until months after I had surgery and I missed out on a lot of opportunities for asking questions, finding support, and finding people I could relate to when I felt like an alien from outer space among my peers. I made what I would say was a “rookie mistake” when I decided to have surgery–I asked my surgeon if I could finish my first year of graduate school then have surgery and he said yes. I can not discourage this approach enough, the emotional weight and burden of scheduling a craniotomy 3 months in advance was unbearable.

1. What were the main reasons why you chose surgery over other options?

I was not given any other option, except watchful waiting and that was discouraged by my surgeon. I live in a relatively small metropolitan area without a large hospital or academic medical center, so I was referred on to three different doctors before I saw a surgeon in another city who could operate on the part of my brain where the tumor was located. So I knew I had a brain tumor for four months before I saw a surgeon who could do the operation. At that point, I was so scared and confused that I would have agreed to whatever treatment the surgeon suggested.

2. How did you prepare for brain surgery, both physically and emotionally? What was the scariest part?

I wanted to be as physically fit as I possibly could be because I hoped that it might make recovery easier especially if I needed physical therapy afterwards. I ran 5-7 miles every single day during the three months I waited for surgery (this may have also been a superstitious ritual). Emotionally, I did not prepare myself at all. I was so focused on surviving surgery that it never once occurred to me that I was having a tumor removed and that the tumor might not be benign (it was benign). When my doctor discussed the pathology report with me, I was really overwhelmed and it took me a long time to come to terms with what I had just gone through.

3. How did you talk with friends and family about your diagnosis? Did it change how they treated you?

I made a lot of jokes. Everyone took their cues from me and treated my surgery like it was no big deal. It was in fact a big deal and when I wanted to be serious, it was hard to get family to treat things seriously.

4. Post-surgery, what helped you get better faster? If you had setbacks, why? If you could do it over again, what would you have skipped or done differently? How long did you really feel like crap?

I kept moving. When I was in the hospital, I walked laps around the neurosurgery floor–I was there for a long time before and after my second surgery so I tried to make sure I was out of my bed as much as they would allow me to be. I had a lumbar drain so I had to be careful, but it was my experience that the nurses and staff were really happy and accommodating if you wanted to be up and moving around. I did have a cerebral spinal fluid leak out of my incision, needed a second surgery, and a few hospitalizations. I don’t think I would have done anything differently, except maybe take the painkillers I was prescribed. I was intent on not taking them–that was stupid. A little more sleep and downtime would not have been a bad thing. I had my second surgery in June and I took a summer class that started four weeks later. I remember almost nothing from the course, I’m certain I acted like a weirdo, and all I wanted to do was sleep. I probably would not do that again.

I really felt like crap for about six months.

5. Are there any hidden upsides to brain surgery? Besides survival, obviously.

Yes, absolutely. I think I have become a much more sincere person since having surgery. It also catalyzed me to make some big life changes. I finished grad school and decided that I want to go medical school, so I’m in the process of applying now. I don’t think I would have done it if I had never had surgery.

Susan, thank you for this generous response. I read it, then read it again, just to absorb all the wisdom and useful tips.

Hi Susannah,

You are welcome! I have been thinking a lot about your question regarding the last mile. I am not sure if it is because I work in healthcare delivery research or if it is because I was a patient who felt adrift in a sea of either too much or too little information–probably some combination of the two.

I think a very real challenge of overcoming the last mile is getting past extreme stories of survivorship. When I began looking online for support after I was diagnosed, I frequently encountered two extremes–either stories of people who survived and then went on to do super human things like compete in triathlons or ultra-marathons just weeks after surgery or caregivers’ stories about the emotional burden of taking care of someone who was close to the end of life. I am glad those people were able to tell their stories, but I simply could not relate. I needed a support community of other patients (not caregivers–this was key) somewhere in between and it was difficult to find.

I was 28 when I had surgery and wanted to find other young(ish) adults whose main concerns were similar to mine–like fertility after brain tumors; how to gracefully start a new job when you just had brain surgery; when and how to ask for time off that you have not yet accrued to travel out of state for follow up; and other mundane things that I think most people my age worry about, but in the context of having a brain tumor.

I do wonder if providers and systems are complicit in promoting these polarized versions of survivorship that might stop patients like me from seeking out an online support community. Before I had surgery, I remember looking for other brain tumor survivors and one of the first search results was a promotional video of the surgeon who was going to perform my surgery and one of his patients who competed in a triathlon just weeks after surgery. This left me feeling like I had one of two options for how I live after surgery–1) I could do perform some amazing feats of physicality and run some marathons or 2) I could need constant care. When neither of these things happened, I wondered where I belonged in the web of survivorship communities: was I sick enough to need support? or was I using my survivorship well enough to deserve support? These are absurd questions, I see that now, but when all you can find online is the narrative that survivorship means doing something big and great–then you really start to doubt whether you are doing it right.

Susan,

I’ve been turning your words over and over in my mind, admiring the insights you share here. You are describing a toxic and false myth about survivorship of all kinds. And you are describing why we need to spread the word about the power of connecting with peers, who can knock down myths.

Many years ago, when I was conducting my first research studies about peer to peer health advice, a more established, prominent researcher publicly said that people shouldn’t go online for first-person/peer health advice because they will only find stories of poor outcomes, the bad extreme. He said that when a surgery or treatment is successful, people move on and never look back, never post online about their ho-hum experience of recovery and wellness. He was right, in a way, but I think he was also wrong. He was making an observation about the “last mile” problem — we can’t connect to the right peer because we can’t find them — and therefore throwing away the idea of looking online at all (classic baby-with-the-bathwater).

I’m going to keep thinking about this and would welcome other people’s observations and ideas.

I’ve experienced being both the seriously ill patient and the advocate of a seriously ill patient. Having a consistent advocate who takes notes, asks questions, and does research is extremely important. Pain, or even just the knowledge of having a serious illness, makes patients become poor note takers, poor listeners, and poor critical thinkers. To be most effective, patient advocates should get legal access to all the medical records and be present (by phone if in-person not possible) at every healthcare encounter.

I view advocacy as paying it forward, although one patient had the opportunity to pay me back in kind. Advocacy has been very rewarding.

Here is a site that offers mostly nontraditional ways of coping with having a cancer diagnosis: thriversoup.com. The author (my sister, Heidi Bright) has passed the 5 year milestone of no-detectable-cancer, after a few years of fighting stage 4 uterine sarcoma. Having suffered a completely different emotional loss since then, the death of her son due to opioid addiction, she has been finding that these coping methods help in tough situations besides cancer.

Thank you, Roselie, for both of these meaty, wonderful comments. Only we who have experience in this crazy maze of health care can say with equal joy and sadness: congratulations to your sister on her NED milestone and condolences for her son. We have to celebrate AND mourn AND try to move forward in a positive way. Again, thank you.

The motivation for a patient to start a blog does not start with a diabolical idea to become THE GO TO SOURCE for giving tips and advice about a particular condition. The blog usually starts as a space for people to share what is going on with their friends and family so they don’t have to be on the phone all day fielding questions.

Then some of us keep blogging… even after treatment… and we find (by looking at our Google Analytics) that the most popular posts on our site have to do with some of these “how to’s.” Interesting, right?

About two years after my diagnosis I started volunteering with Imerman’s Angels (http://imermanangels.org), a one-on-one cancer support organization, where I served as a cancer peer support person for other people just like me (female, same age, similar diagnosis). After helping over 20 people I eventually realized that everyone had the same two questions:

1. What is brain surgery like? (Because they are afraid.)

2. Will I lose my hair from the chemotherapy? (Short answer–not if you are taking Temodar.)

After a while I stopped volunteering with Imerman’s Angels, so I instead wrote a few blog posts focused on these topics. At this point, I have over 500 blog posts… I really should do some editing, and my early posts make me cringe… but they are part of my evolution. In fact, I recently obtained my complete medical record and it is quite interesting to compare my doctor’s notes to my blog posts from the same time period.

Here… are answers to your questions…

What were the main reasons why you chose surgery over other options?

–Unless the tumor is in an inoperable location, or near something immensely crucial, surgery is the best option for removing the most tumor. Radiation and chemotherapy don’t have as much of an impact as tumor removal.

How did you prepare for brain surgery, both physically and emotionally? What was the scariest part?

This is THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE thing I’ve written about brain surgery: https://thelizarmy.com/2012/04/brain-surgery-the-inside-story/

Other blog posts on this topic:

https://thelizarmy.com/2010/01/were-going-to-take-very-good-care-of-you/

https://thelizarmy.com/2009/01/the-top-5-things-that-are-cool-about-brain-surgery/

https://thelizarmy.com/2009/01/top-5-things-that-suck-about-brain-surgery/

https://thelizarmy.com/2012/09/my-movie-moment-brain-surgery/

How did you talk with friends and family about your diagnosis? Did it change how they treated you?

–I immediately started blogging about it because I was on anti-seizure meds and was not thinking clearly. Seriously… If I had been on Twitter in those days I would have tweeted about it.

The iPhone was released in 2007, and I was diagnosed in 2008. Communications technology has revolutionized how patients experience and talk about “illness.” But you know this.

Post-surgery, what helped you get better faster? If you had setbacks, why? If you could do it over again, what would you have skipped or done differently? How long did you really feel like crap?

–What the doctors tell you to do (e.g., take steroids, pain meds, sleep, don’t work or do anything strenuous for 6 months) is pretty spot-on. I recently ran across an email exchange between myself and my neurosurgeon in which I was asking him if it was OK to go on rollercoasters at Disneyland about three months after brain surgery. He said to live it up!

Are there any hidden upsides to brain surgery? Besides survival, obviously.

–Major street cred, bragging rights, etc. j/k But not really. For me, though, I feel like nothing else should be scary in my life. If I can get through brain surgery (twice!), then I can handle any problem.

My husband suffered a minor stroke when he was 38–it was so out of blue. He is so healthy, and not at risk. Anyway… when THAT happened and he was in the ER, I became uber calm and in control. I was in my element. Being an engaged patient prepared me for that moment.

OK, sorry for the long response. (I am not going back to spellcheck!) 🙂

And for those keeping score, that’s two votes for carnival rides/roller coasters!!

Apologies to those who have clicked on a link to this blog and had their screen filled with indecipherable code! I let this site languish while I served in the federal government and am working on an update. Meantime: Glitch City sometimes. Thanks for persevering.

One such brave soul is Molly Marco, who tweeted her responses:

Gosh, for me? Surgery has been the easiest & best part of my whole brain cancer adventure. My surgeon was phenom. I healed quickly.

1) I opted to get biopsy & surgery at same time. It was growing pretty slowly, but started to have seizures. Needed surgery.

2) I didn’t do anything special. My Henry Ford Hospital (Detroit) team was amazing. I wasn’t scared then. Surgery went well.

3) Dang. I just went FB public. Finding out it was grade 3, Anaplastic Astrocytoma was hard. I went loud with it– haha!

I was scared AND tough. It has been an adventure ever since. Yes, they treat me differently– some fades away. Most didn’t.

I feel like I’m star of a class people NEED to learn. How to have cancer. How to live. How to be brave AND scared at same time.

I healed quickly. My surgery was fine. I didn’t have setbacks. My left temporal had been funny for years, so nothing worse.

honestly? I didn’t really feel like crap. I was allergic to Dilaudid (sp?) so I threw up an ice cube. But I was fine.

Chemo has been worse for me than surgery. I had a left temporal craniotomy & my surgeon is my hero. Dr. Air at Henry Ford Hosp.

upsides? Of course! My tumor is, like, 99% (or some percentage) gone! It was the size of an avocado pit! I got time now!

Pre-surgery they had me do neuro psych exam & an uncommon WADA test. I loved that WADA test. I’m left-handed, so they wanted to test stuff.

Apparently, I’m a unique flower who ENJOYED getting half my brains turned off at a time. If anyone gets scared, they should talk to me.

“PwCMoms” also replied on Twitter:

16 hour posterior fossa surgery- no major deficits, and physical therapy was crucial for that. People find out, but they want to help.

THANK YOU!

Another amazing story, the link shared via Twitter:

Imagine: Life With Traumatic Brain Damage

Thanks, Sean!

I was diagnosed almost 15 years ago. My Dx anniversary will be next week! There were no blogs, facebook, twitter, instagram, Tumblr or any form of social media. I’m an old person by survivor standards. I had an astrocytoma grade two that affected my left side. I was supposed to live past my resection. I never thought I’d live to be 25 almost 26. I’ll answer the above questions you have.

What were the main reasons why you chose surgery over other options?

It was surgery or death. I was told they could permanently paralyze me. I took the risk. It paid off.

How did you prepare for brain surgery, both physically and emotionally? What was the scariest part?

I was 12. I only cared about survival and living to live out my Make-A-Wish and life. I knew I was probably going to die but I really wanted to live. I just bucked up.

How did you talk with friends and family about your diagnosis? Did it change how they treated you?

I was visually disabled. Everyone noticed my limp and my gait. Being a very open person I was just honest. Nowadays people are just “inspired” which I think is garbage in the sense that as a disabled person I shouldn’t be anyone’s inspiration. I’m inspiring because I made a series of good choices that paid off. I chose for example not to get pregnant in high school because if I lived long enough to go to college I wanted to have that option. Or choosing not to put myself in bad situations so I wouldn’t get a criminal record so I could have a career in politics. Which I now have.

Post-surgery, what helped you get better faster? If you had setbacks, why? If you could do it over again, what would you have skipped or done differently? How long did you really feel like crap?

I was lucky enough to be sent to UCSF for physical rehab. I slept and read a lot. There was nothing I did besides school and home.

Are there any hidden upsides to brain surgery? Besides survival, obviously.

I don’t fear needles, I get a disabled parking permit for life, I have college paid for because I’m disabled, I take professional and personal risks because I’ve already died and am not scared to die. I survived a brain tumor the worst is already behind me. Oh, and the bragging rights are great too. Not that I believe in the pity Olympics but I can pretty much beat anyone.

So many gems – thank you! And thank you for continuing to hit “refresh” to get past the glitches.

Here’s a new resource, shared on Twitter by Charlie Blotner:

What I Wish I Knew: Tips for Brain Tumor Patient Caregivers

Thanks, Charlie!