Cancer patients were among my first peer health innovation teachers and remain, years later, among my favorite communities to follow. I keep an eye out for hashtags like #gyncsm (gynecological cancer social media), #bcsm (breast cancer social media), and #lcsm (lung cancer social media) on Twitter. I listen to podcasts like The Cancer Mavericks (and pretty much anything Matthew Zachary produces). I also tune in to any discussion of the Unmentionables of health care I can find (like when Alexandra Drane invited Dr. Leslie Schover to teach Health 2.0 conference attendees about how cancer treatment affects sexual function).

My latest source of insights is Elizabeth O’Riordan, a breast surgeon with breast cancer and co-author, with Trisha Greenhalgh (also a clinician and breast cancer patient) of THE COMPLETE GUIDE TO BREAST CANCER (2018). O’Riordan’s latest article, “It is the Little Things That Matter,” about the lessons she learned as a patient about breast cancer treatment is fantastic — and happily, there is a free PDF available (for now, anyway).

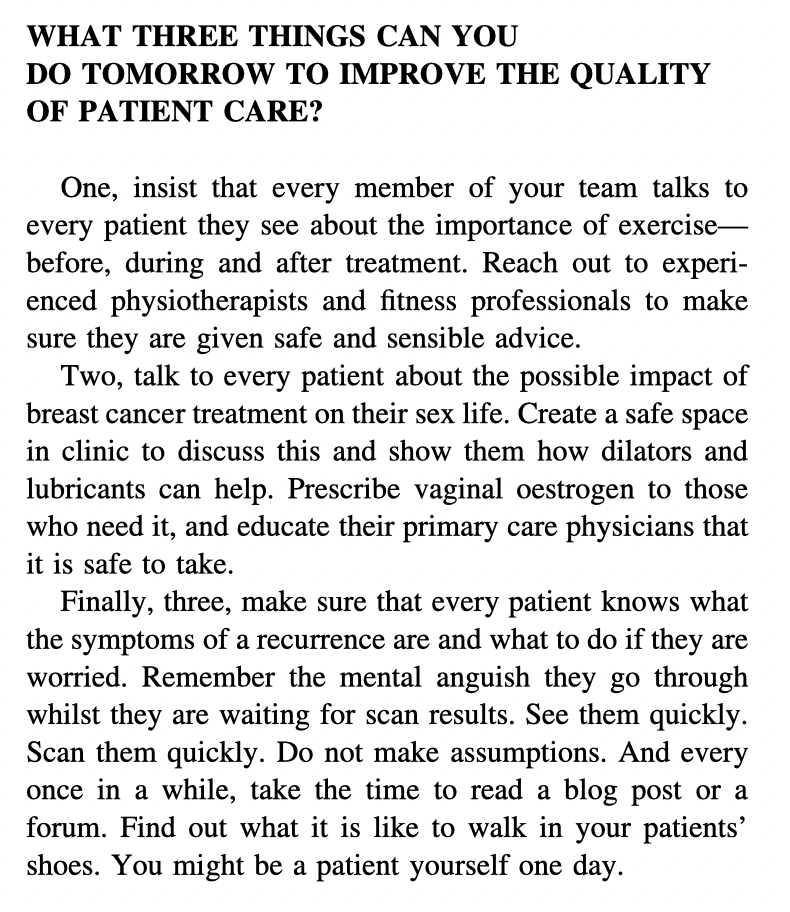

If the PDF disappears, here’s an image of her closing argument:

Again, I loved the article. And I hope it gets the attention it deserves from the intended audience — surgeons of all specialties, but particularly oncology.

But wait, I thought. Hadn’t I heard all three of these suggestions before? Aren’t these among the perennial topics discussed peer-to-peer among cancer patients? And O’Riordan’s suggestion to her clinical colleagues to “every once in a while, take the time to read a blog post or a forum,” is a good one, but which blog post? Which forum?

What if we could create a welcoming, public, international, cross-disciplinary community made up of everyone affected by breast cancer? What if we could use it as a jumping-off point for academic research, community organizing, and advocacy training?

Great news! That community exists.

The #bcsm community is one model for how to create what Jodi Sperber calls “cross-peer interaction” — conversations between and among people of differing status, ability, or rank (meaning: patients, caregivers, clinicians, scientists…) I recently re-read Sperber’s dissertation, Patient Driven, Patient Centered Care: Examining Engagement within a Health Community Based on Twitter, and was struck by how perfectly her findings capture the nuance and magic of peer health innovation and, specifically, #bcsm.

Sperber writes about how the creation of the hashtag community was a peer health innovation in and of itself. Inspired by Dana Lewis’s #hcsm (health care social media) community curation, Alicia Staley and Jody Schoger hosted the first #bcsm Twitter chat on July 4, 2011. Dr. Deanna Attai, a breast surgeon, later joined as a co-moderator, making it a patient-led, but clinician-partnered, community. A 2015 survey of the #bcsm community found that participation lowered people’s anxiety and increased their overall knowledge of breast cancer.

Since then #bcsm has created what Sperber terms “microspurs” (relationships that form as a result of community participation). For example, the founders of multiple organizations drew energy from their participation in #bcsm: GRASP (Guiding Researchers and Advocates to Scientific Partnerships), the Tigerlily Foundation, and COSMO (Collaborative for Social Media Outcomes in Oncology). The #gyncsm, #lcsm, and #btsm (brain tumor social media) communities were inspired by the #bcsm example. And the Metastatic Breast Cancer Project partnered with the #bcsm community to publicize its work and recruit participants.

Matthew Katz, MD, Staley, and Attai collaborated on a history of #bcsm last year that chronicled the community’s accomplishments, its failings, and the dangers of burn-out. How might pioneering peer health innovators be better supported? How might we translate what #bcsm has learned about patient care into lessons that more clinicians can absorb?

Beyond reading academic journal articles and dropping into a patient forum “every once in a while,” what are some other ways for clinicians (and others) to learn about the insights hatched in other peer patient networks? Where else have you seen successful examples of cross-peer interaction?

Please let me know what you think in the comments below.

Image: Walking the Black Diamond Trail, by Jo Zimny Photos on Flickr. I thought it was a good capture of both the advice to exercise during treatment AND to walk the path of the patient with them.

Re: How might pioneering peer health innovators be better supported?

This is the most important question. #BCSM has been an important lifeline for the breast cancer community over the past 10 years, and it has been for me as I started out on my path. I am incredibly thankful to Alicia Staley for her mentorship, hard work, and her ability to foster connections in a way that is supportive, kind, and respectful of patients. So many patient communities have thrived because of Alicia’s work, and that of Dana Lewis, Liz Salmi, Janet Freeman Daily, and so many others.

A problem exists: we are tapped out, burned out, exploited, and harmed on social media. It’s only gotten worse since the pandemic as we watch our friends lose access to care and have watched deaths in our community. This is part the work when leaders like Liz, Alicia, and Dana choosing to support patient communities through our collective experiences rather than just seeing us as an abstract….as just data or the “market” or “patient population” where we exist. I would dare say that Alicia, Liz, Dana, and others are some of the most important healthcare innovators of our generation.

Without resources, peer support communities seek each other on social media when we fall through the cracks of the healthcare system. Our communities are support groups, yet too often we are treated by outsiders as a resource to be used rather than humans with rights. (Recent talk about that here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ksj2zsWzwVs). Without supporting these communities, and the trailblazers burn out. Their work is often overlooked, appropriated, or the value of their work is underplayed while they continue to work toward equality of our kind – patient innovators.

I often think about how many device companies benefited from Dana and so many T1D activists in the #OpenAPS movement’s made incredible innovations in CGM. It’s hard to see that these same communities are now aggressively getting ads targeted from device companies….. selling CGM devices back to the Diabetes Community. I think about how the BRCA community is aggressively targeted and solicited with chemo ads and life insurance scams while we remain trapped on Facebook…3 years now. It’s bad out there.

Our communities on social media need digital rights.

Peer support communities need true allies to help us tackle this problem – including clinicians, health systems, technology experts, and even the industry. And it’s a very hard problem when new generations of patients will continue to gravitate to new social media platforms.

We seek to protect the lifelines for communities like #BCSM, and seek institutional support / legitimacy of the incredible work we accomplish that changes healthcare.

Andrea, thank you. You packed a lot of insight & history & context into your comment. But I’m going to ask for more — whether from you or from others reading this.

Yes, communities like #BCSM should be supported. But by what means? By whom? What models can we look to, what paths can such peer-led communities follow? Where else have we seen grassroots organizations gain institutional backing?

I think that learning health networks and civic data trusts may be important means to develop the institutional legitimacy and digital rights for communities. Here are two introductory resources to explain both.

Civic Trusts: https://www.cigionline.org/articles/reclaiming-data-trusts

Learning Networks: https://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/research/divisions/j/anderson-center/learning-networks

How? We need to test these models to see if they work, and how stakeholders respond to working in a new model…specifically for social media. I invite anyone reading this to join us or reach out to me to talk further about this. IMHO no substitute for practicing governance and testing whether these models will work specifically for peer support groups that exist on social media. I’ll be devoting the better part of my next year trying to get more clarity on what/how/whom. I am hoping we learn how orgs may adopt the early principles we worked to create through The Light Collective. https://lightcollective.org/trust/

As for examples of grassroots movements gaining institutional backing… HL7? The civil rights movement? The disability rights movement in the 70’s? Wozniak’s homebrew computer club from the 80’s?

There’s nothing is quite like this problem of how… which is why it’s really really hard. I thought I’d have all the answers by 2019 and then a pandemic hit. But not giving up till we figure out a better answer than what I have now.

PS:

Speaking of HL7 I’m glad Dave replied below…as he’s the one who has gotten me plugged into the FHIR crew. Here’s a great podcast to share what happens when hackers meet standards ppl. ( ;

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/conversation-alissa-knight-john-moehrke-ins-outs-fhir/id1533468758?i=1000530851279

Wow, I missed that history of #bcsm article last fall – thank you! And double-wow, a Journal of Patient-Centered Research?? Never heard of it!

I’ve printed the new Katz et al article to read – can’t comment on the details yet – but what I sense is that we’ve long ago crossed a threshold in how care comes to happen. We’re now in the era where people outside academia can develop (or can be!) interventions that spread knowledge and interventions that achieve empathy.

Given the financial pressures on care organizations in the US these days, it no longer surprises me that people working in “the system” are less able to be as caring as most want to be (in my experience); patient communities have no such pressure: as I said during my cancer, “I nothing better to do with my time!” than go deep and wide on learning about my condition and what to do about it.

> A 2015 survey of the #bcsm community found that

> participation lowered people’s anxiety and

> increased their overall knowledge of breast cancer.

Thirteen years ago you nailed that problem when you blogged https://participatorymedicine.org/epatients/2008/03/flashback-to-2001.html about the AMA’s 2001 new year’s letter, in which they said “the Internet cannot replace a physician’s expertise and training.” (Notice the implication that Web use would “replace” a physician, which is nuts. How can smart people make such mental errors??) They continued, “trust your physician, not a chat room.”

A cultural vestige of the old days, which we must educate out of physicians, is the “stay off the internet” problem. I’m appalled to learn recently that YOUNG doctors (newly minted) are telling some patients to stay off the Web – because it takes up their time. So I’ll ask: how might we figure out how patients can use the Web productively (as they themselves define it) without “bothering” their busy doctors? How can we make that knowledge widespread?

How indeed? One reason I’m writing my book is to shine a spotlight on the huge pile of evidence for the good work that peer communities do, unpaid and often unacknowledged by the institutions that benefit from it (people who are able to stay well & out of the hospital are much less expensive, to name just one outcome).

Thank you for linking to that 2008 post which happily still links to the PDF of the original AMA press release. What a blast from the past.

Your comment reminded me to bring up this classic set of findings:

“In March 1999, Tom Ferguson, a medical doctor and self-care advocate, and Bill Kelly, cofounder of Sapient Health Network, fielded a survey of an online patient community which asked members to rate the most useful resource for twelve dimensions of medical care. Online patient groups were rated more useful than health professionals on ten of the twelve aspects of care, such as practical knowledge and help finding other resources, whereas specialists and primary care doctors received higher ratings for diagnosis and managing a condition.

It was a small sample of a single patient group (just 191 respondents), but it served as the inspiration for the following series of questions. In our national telephone survey, all adults were asked which group is more helpful when they need certain types of information or support: health professionals like doctors and nurses or peers like fellow patients, friends, and family.”

Further on in that report, Peer-to-peer Health Care, I wrote about the Pew Research Center’s national survey results and included quotes from fieldwork I’d done in communities of people living with rare conditions:

“A clear majority of adults favor friends, family, and fellow patients when they need emotional support in dealing with a health issue: 59% say that, compared with 30% of adults who say they rely on health professionals for such support….

One adult living with a rare condition wrote about the way friends and family formed a safety net around her: ‘People like to help. And in the face of an incurable, rare, awful disease that leaves me at times helpless, people not only like to help, letting them help is a gift I can give them, a way to take some of the power and fight back against the currently unfightable.'”

And here’s a quote that shows how carefully people navigate health advice gathered offline and online:

“One mother caring for a child with a rare condition wrote, ‘In my experience of dealing with a rare, serious, and chronic disorder, specialist doctors are typically the ‘go to’ people for medical advice involving medication or surgery … Sometimes the doctors have not been as knowledgeable about the feeding issues which are of great importance. Sometimes other parents have some really good advice in these areas.’ She qualifies that statement, however, noting the seriousness of the situation she and other people face: ‘We patients and caregivers of patients have to be very careful not to generalize from our experiences. Sharing information about experiences with medications and symptom is very helpful as long as extrapolations are not made.'”

Since this blog is my outboard memory, here’s a tweet that resonates with what we are discussing.

JAFERD, MD (@Supermansings) whose profile identifies them as an ER doc, writes:

“Pro-tip:

If you have a pediatric patient with a rare genetic disorder that you don’t understand as much as the parents do, and the parent tells you that they have a Facebook page chronicling their child’s journey, follow it. Learn.”

Followed by:

“It takes you from the OMG, why did nature allow this to the- OMG when she’s not sick she is a bringer of light state of mind.”