My prepared remarks for the Quantified Self Public Health Symposium (here are some notes from the event):

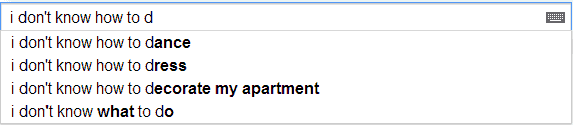

You know when you type the first few words of a query and Google suggests the rest based on what thousands of other people have typed next? There’s a Twitter account called Google Poetics that takes those suggested phrases and makes a poem out of them.

Reading each one, you can catch a glimpse of people’s worries, hopes, dreams, and mysteries.

Start a query with “I don’t know how to…” and Google suggests:

Google Poetics takes the raw stuff of humanity, polishes it up, and reflects it back as something kind of beautiful.

That’s how I think about data. The raw, real stuff of life, polished up, reflecting back.

The Pew Research Center, where I work, uses data to hold up a mirror to society so people can see themselves more clearly. We don’t tell people what to do about the reflection. We just want you to see yourself as you really are.

That’s the beauty and the peril of data, isn’t it? To see ourselves as we really are. Who is ready for that? Who is ready to stand naked in front of the mirror of data?

Who would prefer to just catch a glimpse of the truth every once in a while? And if you do find out the truth about yourself, do you want to share it with anyone, or keep it secret?

Hold that thought.

In September 2012, the Pew Research Center and the California HealthCare Foundation fielded the first national survey to measure the magnitude of health data tracking. We did it for 3 reasons:

1) The medical literature shows that tracking is a low-cost, effective health intervention for losing weight or managing chronic conditions.

2) My fieldwork in a variety of online patient communities turned up multiple examples of home-grown, kitchen-table tracking solutions.

3) Media stories about health tracking were not citing any data, which to me is unacceptable.

We found that 7 in 10 US adults are tracking some aspect of health, their own or someone else’s.

Here’s how it breaks down:

- 60% of U.S. adults say they track their weight, diet, or exercise routine.

- 33% of U.S. adults track health indicators or symptoms, like blood pressure, blood sugar, headaches, or sleep patterns.

- 12% of U.S. adults track a health indicator on behalf of someone they care for.

Women are more likely than men to track weight, diet, or exercise routine. Women are also more likely to track a loved one’s data.

College-educated adults are more likely than those with less education to track weight, diet, exercise routine – but not symptoms, which is spread more evenly among all education groups.

People age 65+ are the most likely age group to track health data of any kind. Let’s keep that in mind.

Half of all those who track say they do so on a regular basis, half when something comes up, like a symptom flare or a new goal.

Now, brass tacks. How do they keep track:

- 49% of health trackers just keep track in their heads.

- 34% use pencil and paper, like a notebook or journal.

- 8% use a medical device such as a glucometer.

- 7% use an app or other tool on their mobile device or phone.

- 5% use a computer program, like a spreadsheet.

- 1% use a website or online tool.

Note that we allowed people to give us more than one answer, so it won’t add to 100.

One limitation of our study is that we didn’t get specific about wearables. If I were writing the survey questions today, I’d add a specific choice to capture those.

18-29 year-olds are the most likely group to use an app or mobile tool.

Paper is the technology of choice among trackers age 65+.

I’d like to focus on the people who could really use our help: people living with chronic conditions and people who are caring for loved ones.

45% of US adults are living with a chronic disease. About half of them are dealing with 2+ conditions. We identified what we call a “diagnosis difference” – holding other demographic factors constant, people living with chronic conditions are less likely to have internet access or to own a cell phone, but more likely to track. 8 in 10 track some aspect of health.

39% of US adults are caring for a loved one, such as a parent, a spouse, or a child with significant health issues. Of those, 3 in 10 track their loved one’s data.

Both groups – people living with chronic conditions and caregivers – are more likely than other trackers to use pencil & paper and medical devices.

A special note about caregivers: Medication management is a significant burden. 4 in 10 caregivers are managing their loved one’s medications and just 7% of caregivers use online or mobile tools, such as websites or apps, to do so. Two incredibly important questions for caregivers are: “What drugs is mom on?” and “Has she taken her meds today?” Those are tracking questions and there’s got to be a better way for caregivers to answer them.

Here’s what’s important about these groups: Tracking health data is not a hobby. They may not have a choice. They are trying to use data as a mirror, to see themselves or their loved ones more clearly and do the best job they can, trying to stay well, given the tools and knowledge they have.

Kim Vlasnik, who is living with diabetes, wrote: “As patients it’s not enough that we have to live with the disease itself. We have to live with the data management as well.”

So back to what I was talking about at the start: What mysteries are people trying to solve about themselves? What questions are they asking about their bodies, about their families, about their communities?

And are they ready to stand naked in front of the mirror? Do they want to have the unforgiving bright light of numbers on a screen? Or is it nicer, easier – more meaningful, even – to write the numbers down in their own handwriting, on paper?

Are there other reasons why paper persists? Is it the ritual that people crave? The sense that they are doing something?

I was thinking about this recently because it was my birthday and two things happened:

1) I made my own birthday cake.

2) I went in for my annual check-up.

First, the cake. I’m a pretty good home baker, but I was in a hurry, so I used a cake mix. As I held an egg in my hand, I thought about how, in the 1930s, manufacturers successfully created a “just add water” cake mix. But research showed that women liked the ritual of cracking open fresh eggs. It made them feel like they were doing something. So manufacturers took out the dried eggs and cake mixes became a huge segment of the convenience food market.

Second, the check-up. Did you know that some women avoid going to the doctor because they don’t want to step on a scale? What else are they avoiding, to the detriment of their health? How can we be gentle in our approach to their concerns?

As we go forward today, let’s keep in mind the reality of people’s lives. What secret questions are they asking? What rituals do they cherish? How can we help them to polish up the mirror and maybe, just maybe, stand naked in front of their data?

hi Susannah,

Maybe I am hopelessly pragmatic, but it hadn’t occurred to me to think of data gathering as about secret questions; I think of problems and purpose. That’s because I personally track my own data when I think it will help me solve a problem (ex:I need my baby to sleep better at night), or if I think I will need the information later (I don’t look at the tracked financial data until it’s tax time).

I am constantly asking the families I work with to track things: blood pressure, use of as-needed medications, pain, etc. I find that most families aren’t nearly as interested in tracking as I wish they were. I think this is partly that they are very busy w their caregiving, and tracking is not yet as easy as it should be. But I also think they don’t always realize how much this information can help us (clinicians) help them with their problems.

So many seem to hope that clinicians have xray vision and can tell them what to do about their problems or medication. But we can’t, unless they can help us capture data.

Eventually I hope your research will help us understand why people track the health data that they do. Thanks for this post.

Thank you, Leslie.

I’ve been sick in bed all day — a lovely Norovirus is afoot this spring — thinking about all the various kinds of questions people have about their bodies and the ways they track.

I think our survey was a good start toward understanding the broad outlines of tracking in the U.S. but there indeed is so much more work to do to understand the realities of people’s lives.

Feel better soon!

Your surveys are always a good start for the rest of us; am looking forward to seeing what your mirror shows next.

The video for my talk is now online:

http://vimeo.com/95563082