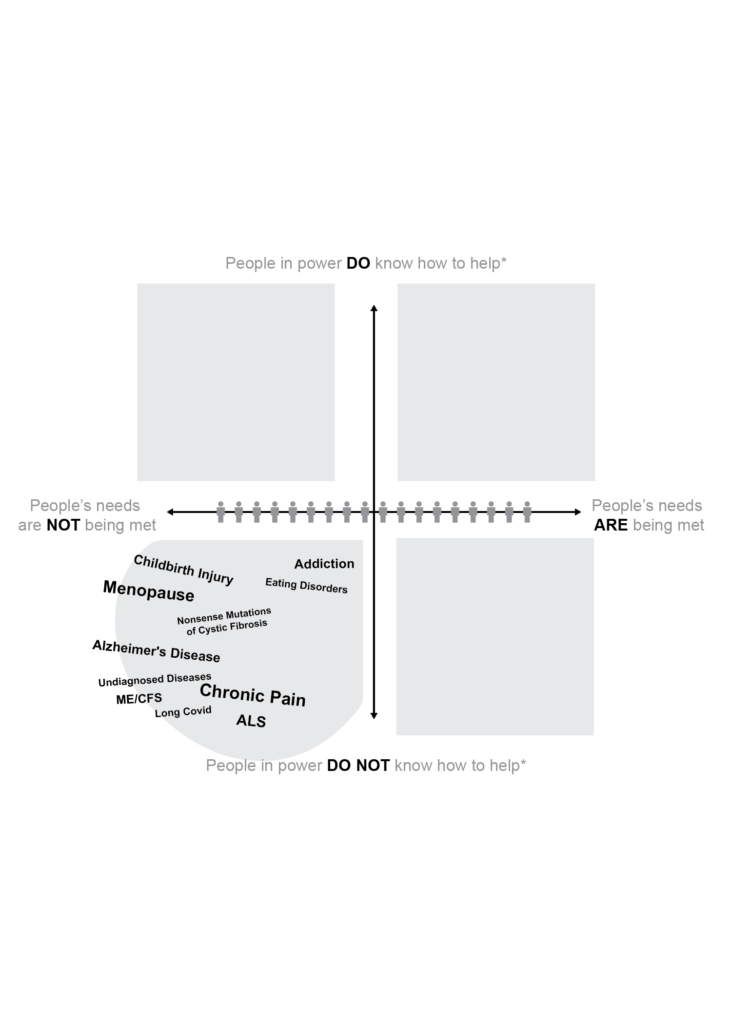

For years I tried to find ways to explain the particular challenges facing people with undiagnosed and rare health conditions. I decided to create a visualization showing the wide spectrum of people’s health needs and I’d like some feedback on it.

Imagine a horizontal line. At the far left side are the people whose needs are not being met. Their questions are not being answered – or even explored – by scientists and clinicians. Friends and family may not know or understand what is going on. They are totally alone and at sea.

Here’s a point that is important to my vision of this spectrum: People get to decide if their needs are met and their questions are answered. It is not for the rest of us to say. If a remedy does not make sense to someone, even if it makes sense to a majority of people, then that person’s needs are not met. In this model, we must listen to the people in pain, the people who are suffering, the people with doubts.

At the far right of that horizontal line are the people whose needs ARE being met by the current health system. Their questions have been answered to their satisfaction. They have a diagnosis. There is not only a range of treatments available, but scientists are working diligently on formulating new, better ones.

Let’s go out to the far end of the spectrum and say that people in this segment of the population can both tolerate and afford the treatments offered – and the therapies work. A cure or other resolution is at hand. Maybe their health condition is even something that is celebrated, like a healthy pregnancy and uncomplicated birth.

Now add a vertical line to the chart. At the top of the line the text reads: People in power know how to help.* These people control access to valuable resources in the current health care system as clinicians, payers, policymakers, regulators, pharmaceutical and device company executives, investors, researchers, etc. In the best-case health care scenarios they recognize, understand, and are compelled to come to the aid of people who are suffering.

At the bottom of that vertical line the text reads: People in power do NOT know how to help.* Some health conditions or physical disabilities appear to be unsolved mysteries. Onlookers have little or nothing to offer besides sympathy. In the worst-case scenarios, people suffering from certain symptoms and challenges are essentially invisible.

Notice the asterisks attached to these labels. Upton Sinclair observed that, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.”

Imagine a magnet at the top of this chart pulling people off the horizontal line depending on whether the current health care system recognizes their health condition and knows how to help – or not.

For example, people whose needs are not being met might be pulled up into the upper-left quadrant because people in power at least recognize their problem and have ideas about how to solve it, such as people newly diagnosed with a curable disease. Good news may not have spread to everyone who needs to hear it.

The club that everyone wants to join is the one in the upper-right quadrant where people’s needs are met and people in power know how to help. Questions are answered. Cures are at hand or solutions are straightforward, like a broken arm that can be set and stabilized.

Imagine a magnet pulling in the other direction, though, to the world where people in power can’t — or won’t — help. The most dismal prospects are among those who find themselves in the lower-left quadrant: Their needs are not being met and they are essentially invisible to people with power.

Here’s how my colleagues Roni Ayalla and Michael Bean of Sandpaper Productions rendered it:

First, what do you think about the overall concept? What do you like about it? What’s missing? Besides how to move yourself and your community to the upper-right quadrant (which I’ve seen done — stay tuned).

Second, what else should go in that bottom-left quadrant? What shouldn’t be there? Comments are open.

Disclosure: I am writing a book for MIT Press about the peer health revolution and this post is part of my process. Thanks for your help in thinking this through!

Special thanks to Matthew Trowbridge, MD, who workshopped the vertical axis labels when this was still a drawing with about a hundred Post-it notes. Thanks also to e-Patient Dave deBronkart who reviewed it and made key suggestions, like the broken-arm example.

Featured image: “What?” by Véronique Debord-Lazaro on Flickr.

Nice, Susannah! In the bottom left – some ideas: Lyme, Ehrlos-Danlos Syndrome, autoimmune diseases.

There’s also something about the patient knowing how to help themselves, even if people in power don’t know how to help. For example, I have mast cell activation syndrome, but I’ve never been diagnosed formally. It’s not something most doctors know what to do with. But I’ve done the research to know how to adapt my diet and lifestyle to keep my symptoms under control. So I moved from the bottom left, to the bottom right quadrant.

Thanks, Katie! Great additions to the bottom left quadrant.

And I love your description of how you moved from the bottom left to the bottom right. That’s exactly what I’m using this model to describe — the positive effects of peer to peer connection and problem-solving.

@ALSAdvocacy posted these thoughts on Twitter:

1) Mom to doc: “If you can’t cure it, then at least help us deal with it.”

Healthcare delivery wasn’t good at at helping us deal with it.

[My reaction: Yes, exactly. If you can find peer patients and caregivers, they can often help you to deal with the incurable, unchangeable situation you find yourselves in.]

2) I propose a third dimension with the range from People in Power Don’t Think It’s Their Job to Help … to … People in Power Think It’s their Job to Help.

[I like that refinement — what other dimensions do people see?]

3) I think it’s more of a cube where people can get stuck in a corner where needs are not being met and healthcare delivery knows there are things that can help but abdicates that job for someone else to pick up.

[I’d love to hear specific examples of this.]

Alicia Garceau tweeted a nomination for the lower-left quadrant: Autoimmune Encephalitis. (I clicked through to her profile and read the article attached to her pinned tweet: “The Wonder Years: Inside a Medical Mystery” about her daughter Rory. Spoiler: It ends well.)

Peg (@ethnobot) suggested: Post concussion(s) syndrome(s)

Liz Scherer tweeted: Reproductive HC (large category, I know). And a link to: “Attitudes to long Covid are straight out of the ME playbook – history must not be allowed to repeat itself”

Shannon (Sartin) West tweeted: Post-viral everything, any hormonal issues in women, cancer (especially in the 25-50 age range), metal health in general.

And Kristen Honey replied: Post-infectious everything, beyond only viral — for example, #Lyme & #TickBorne conditions => #PTLDS (Post Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome)

Lyme isn’t rare — 476,000 cases in USA each year! — but an orphaned disease

Endometriosis is another interesting orphan in #WomensHealth

(Leading me to slap my forehead that I hadn’t remembered Abby Norman’s #AskMeAboutMyUterus — here’s a link to the NYT Book Review: When Doctors Don’t Listen to Women)

A few more ideas gathered from LinkedIn comments:

– “a broad array of mental health issues” (Jessica Trevelyan)

– “The undiagnosed label is interesting, what about vague diagnoses/symptoms? GI issues (generally or IBS), migraines, grey area things like “preclinical” something (hypothyroidism as an example). Also potentially relevant, characteristics or identities, like people who “look healthy.” Also: Perhaps another, anything non-surgical that might be resolved with physical therapy. Too bold?” (Lelia Gessner)

– And another vote for autoimmune diseases (Cam Teems)

And John Reaves wrote: “It certainly raises some interesting questions about the relationship between having a solution (knowing how to help) and providing a solution (meeting needs). In designing innovation workshops, I’m often aware that having an idea for how to address a challenge shapes how we perceive it. But I’m not as sure that the diagram maps to reality unequivocally or in a simple way, and therefore what conclusions we are meant to draw from it. Knowing a solution and meeting needs are, of course, always relatively close together (not really at 90 degrees from each other), particularly if the solution is both effective and affordable. Similarly, not knowing a solution and not meeting needs inevitably overlap. There are many examples, of course, where we have a solution but aren’t meeting needs, or where a solution could be found if enough resources were devoted to it. Those seem to be areas we need to explore … why, what factors are at play, and what to do about it?”

The “People in Power” categorization bugs me a bit. Does that imply that I (as the citizen / patient) am not in “in Power”? I may not have all the power, but I have some. I don’t want to lose that perspective. And a clinician or healthcare administrator who’s bound by everything from HIPAA to Medicare regulations to the latest city health system mandate is “in Power”? One of the things I’ve absorbed from a distressingly messy training, including anthropology, sociology and systems thinking, is that everyone in the ecosystem is constrained by something, and sometimes the higher in a nominal hierarchy they are placed, the stronger the forces and limitations they juggle. Is there a more specific categorization possible that tells us more about who we think this group is and what levers they are able to control?

John, thanks so much for making the jump from LinkedIn!

I appreciate your point about the term “power.”

How about “Mainstream health care” instead of “People in power”?

🙂 I do like that better. There’s certainly a “medical-industrial-governmental complex” which has murky incentive systems and a whole lot of inertia.

Here’s a question that’s right next door to the one you’ve posed regarding health conditions. Let’s assume that we’re just as interested in making the existing (best practices) quality of care available to more people as we are to expanding the additional conditions we can treat. And let’s assume that some integration of new technologies (AI, robotics, sensors, 3D printing at POC, mobile and low-code applications and cloud-based data management) could cut costs and make personalized distributed care easier, not incrementally but radically (e.g. by 2X to 10X), would either People In Power or Mainstream Health Care tend to support or get in the way of that vision?

As I read more about your amazing work, I do realize that the issue above might not be as relevant in a peer health context as questions related to specific conditions, if peer health communities organize around conditions. But it does seem like some of the potential developments that support a radically more affordable and distributed healthcare delivery system might also support peer health initiatives. Fruit for further discussion!

Thanks, John! I love the questions you’ve posed. I think the tech advancements you listed are disruptive forces that will enable personalized, distributed care — as will the peer to peer connections that I’m focused on. Can’t wait to share more about what I’m working on and so glad that we’re thinking on this together!

I’m exploring your blog posts on peer-to-peer health care as well as on the use of digital media for health by young people, both of which seem very relevant to discussing a broad future-focused vision that we’ve dubbed RAD (radically affordable and distributed) healthcare delivery. I’ll come back with some more specific comments, all suggestions welcome!

Lisa Suennen, aka @VentureValkyrie, posted a fantastic, in-depth response to this post on her blog:

Doing My Part to Add Cynicism to the Story – In Search of Unaddressed Medical Solutions

https://venturevalkyrie.com/doing-my-part-to-add-cynicism-to-the-story-in-search-of-unaddressed-medical-solutions/

A few quotes:

“It is pretty clear that ‘People in Power’ – and who they are may vary in different situations – sometimes do not help because they do not know how. But there are also many situations, I would contend, where they do not help or don’t care to help because: 1) they do not believe it will be profitable for them; or, 2) they do not believe the conditions are “real problems” that warrant help and resources…

“It is also pretty clear that many rare diseases go unaddressed (and companies seeking to address them go unfunded or are poorly funded) because there is no drug price tag in the world that could make up for the fact that there are only a handful of patients with the problem…

“Anyway, my point is, there are companies in that lower left quadrant that definitely do meet the definition of “people in power do not know how to help.” Alzheimer’s and addiction are high on that list. But in both of those cases there is a hell of a lot of trying going on. Zillions of dollars are pouring into scientific and commercial efforts to serve those markets and patients, but no one has yet fully cracked the code. This is a lot different than what is happening around the conditions that have little to no money chasing their cures and/or conditions where few scientists and researchers are investing time and brain space because it’s just not worth it, either due to financial challenges or their own psychological ones…”

Her suggestion of an additional framework within my framework is a visual worth clicking through to see.

Thanks, Lisa!!!!

Really neat post! A couple of thoughts do come to mind.

– I’m not sure I agree that “everyone wants to join” the club in the upper right. Honestly, everyone just wants to be on the right side, with their needs met, and who cares what people in power know or think they know about helping. Following Lisa @VentureValkyrie’s lead of adding cynicism, there are plenty of health care issues where the patient’s needs can be met with low cost lifestyle interventions, but the “people in power” have an incentive to gin up a blockbuster drug to accomplish less for more money. No one knows what to do with the lower right quadrant, but the people there are happy.

– The upper left is potentially the most interesting because the knowledge is often what creates the opportunities to meet people’s needs. You could map Stanford Biodesign on to your figure: if you really understand the left side of your chart, you’ll find some opportunities that are farther up the Y axis than you suspected and that can allow a rapid shift to the right.

– The real tragedy probably also lies in the upper left. Mapping it into 3D under @VentureValkyrie’s model, I’m picturing some sort of gravitational sink hole of cynicism that sits near the center in the upper half. Needs aren’t being addressed, people know what to do, and yet solutions just get sucked down into a void like the poor unfortunate souls in The Little Mermaid movie.

Thank you! I love these observations and insights. You’re absolutely right — most people don’t know and don’t care what mainstream authorities know or don’t know about their issue. Most people don’t want to think about health. They want to live their lives.

Will meditate on the “gravitational sink hole of cynicism” that lies in the upper left (and likely lower left) quadrants. Uggggh, that is a nasty truth to ponder.

Susannah, this is your “bodyguard” from Startup Health 2018 (might have been 2017). You can blame Lisa S. for my response as she urged us to do it. First, thank you for tackling the subject; you’re giving a critical voice to those not being heard. Second, I would include all “cognitive function” illnesses in the bottom left corner, not just Alzheimer’s disease. Third, to use your analogy, the big question is how do you “flip the magnet” so more people with the disease in the bottom left quadrant end up in top right. I would suggest 3 strategies: 1) raise awareness about these illnesses; give everyone a reason to know – this could be you, a family member, a loved one in the near future, we are all living longer; 2) need to shake the money tree – federal funding, pharma charity….remove reasons why the “market” is not attractive, perhaps looks the “CARB-X” model funded by BARDA for antibiotic resistance research, and 3) increase resources allocated to this quadrant….need $$ but also need motivated researchers to pick up “the flag” and run with it.

Fantastic insights — and so great to hear from you, Carl!

It’s funny to think of being at such a crowded event that I’d need a “bodyguard” — will we ever get back to being in those fun, chaotic rooms? Hope so.

Another dimension of this that I see often enough is that clinicians know that there is information out there that *could* help (like for menopause or some of the conditions with a lot of patient advocacy and peer communities- ie just offering up a link would be helpful!). But, to get that info to patients requires time and also figuring out where to put the info so it’s easily accessible in the clinical workflow. Both of these factors prove to be major barriers. Educating patients just isn’t profitable in an FFS world. Nor is spending the time it takes to accurately render a diagnosis.

Spot on, Stacey. We are in a transitional moment for peer health innovation.

There is a 40-year evidence base showing that peer support has a wide range of positive effects across many health conditions.

There is also a growing grassroots movement to build patient-led communities for support, information exchange, and clinical research (just to name three points along a spectrum of community types).

There is an awakening among corporations that connection is a commodity that can be monetized and therefore they should invest in creating social platforms (which are not built for health purposes but people use them anyway — see: Facebook).

There is a growing sense among some clinicians that their connected patients, who are part of peer health communities, are more ably navigating the health care maze compared to their isolated, disconnected patients.

It’s that last point that you highlight with your comment. What can be done to spread the knowledge among clinicians that peer health groups can be incredibly useful to patients and caregivers? How might we boost clinicians’ confidence to recommend peer support and problem-solving communities to their patients?

My answer: Pull all the best evidence & storytelling in one place and publish it as a book 🙂

But in the meantime, I’d love to hear what other people see in the field. Who are the other players who might help build and support social platforms that respect patient data rights, for example? Who else, besides clinicians, has a stake in keeping people well (for example, payers, both private and public, ie, governments; employers…)?