When the organizers of a National Cancer Institute workshop on social media and clinical trials invited me to speak, they said:

We have an ethical obligation to understand social media. Social media is not just trendy. It’s a tool, an opportunity to act in an ethical way, not only to increase recruitment but to help match patients to researchers for a conversation.

It reminded me of something I’d read years ago:

A powerful global conversation has begun. Through the Internet, people are discovering and inventing new ways to share relevant knowledge with blinding speed. As a direct result, markets are getting smarter, and getting smarter faster than most companies. These markets are conversations. Their members communicate in language that is natural, open, honest, direct, funny and often shocking. Whether explaining or complaining, joking or serious, the human voice is unmistakably genuine. It can’t be faked.

That was written in 1999 – nineteen years ago – as part of the introduction to the Cluetrain Manifesto. An often-cited estimate of time lags in translational research is 17 years, so even by that measure, clinical trial design is late to the adoption of the Cluetrain principles. To speak in a human voice. To engage in a conversation.

I want to applaud the organizers. Social media is an opportunity to act in an ethical way.

I also want to call out the shame of this situation. I’m glad we are gathering to work on this. But we are late.

We travel backward and forward in time every day in health care. Backward to a time when people think patients should be seen and not heard. Forward to a time when miracles happen thanks to new discoveries. And a big part of discovery is in the work of clinical trials.

To illustrate what I mean by time travel, here’s a tweet from Liz Salmi that sounds like it could have been written in 1950:

A few months ago I attended a meeting w/a group of cancer researchers. I piped up about how patients are ready and waiting to help prioritize research agendas. Dude at the end of table suggested best way patients can help is by donating our bodies to research after we die.

Paul Wicks of PatientsLikeMe replied, “I would like to think I’m too polite to have snapped back ‘You first’.”

Social media allows Liz, Paul, and other experts to compare notes across time zones, cheering each other on and sharing what they learn in a global conversation. Twitter stimulates the marketplace of ideas.

In thinking about the health care marketplace, you might say that clinical trials are a product that few people want to “buy.” First of all, nobody wants to be sick enough to be in the target market. Second, those who are “selling” often do not approach potential customers with the respect they deserve and are coming to expect. The result: People are not buying what researchers are selling. The market recoils from the usual way of doing business, so researchers AND patients are forced to figure out alternatives. The National Cancer Institute wouldn’t need to hold a workshop if the system was working.

My role is often to provide data that helps people convince their colleagues at every level to take social media seriously. Because if sunlight is a disinfectant, data is a solvent. Let’s use data to break down resistance to new ideas.

The data below is from the Pew Research Center. If you are intrigued by technology trends and the social impact of the internet, and you crave data, dig into their reports. They provide context and compass points as we navigate a shifting landscape.

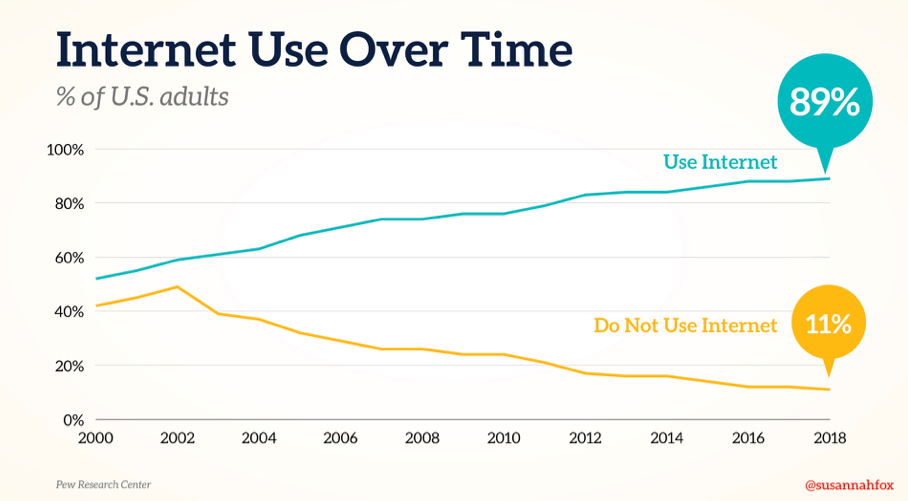

The first revolution was basic internet access. In 1996, just 14% of U.S. adults had internet access. Now, it’s 89%.

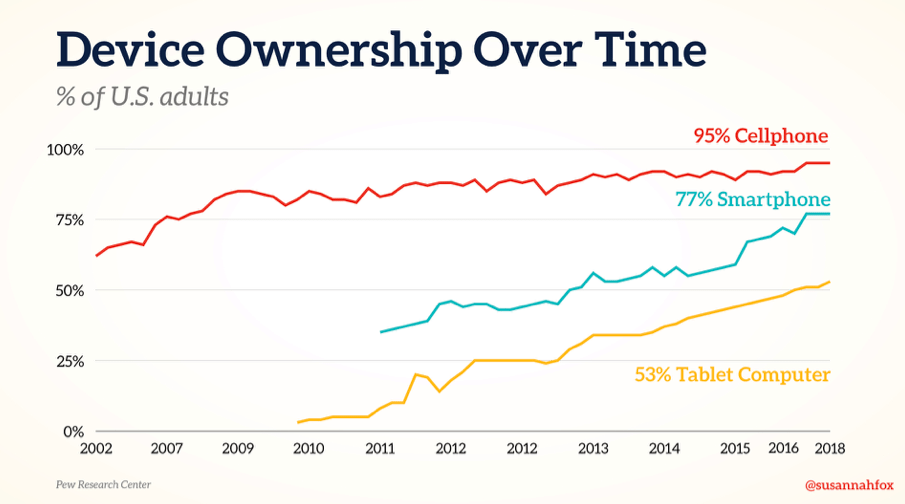

The second revolution enabled information everywhere, at all times – the mobile era. 9 in 10 U.S. adults use a cell phone – majority are now smartphones.

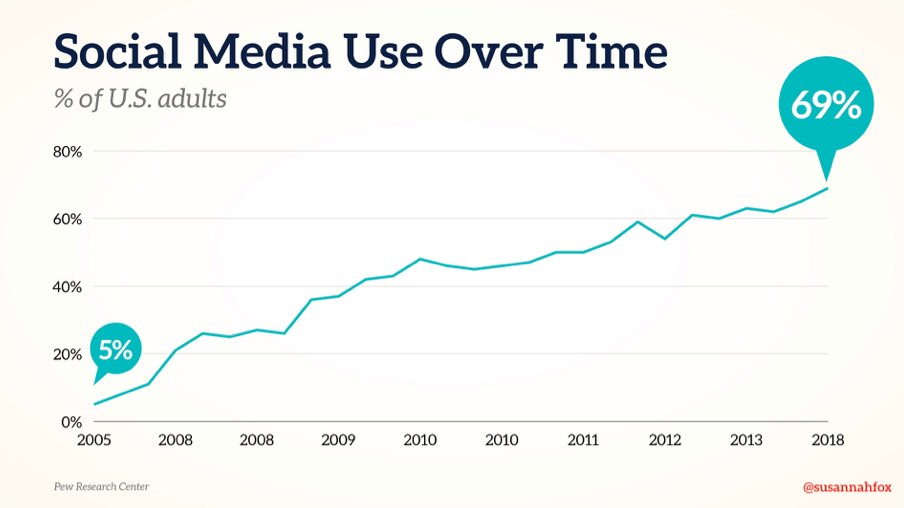

The third revolution, which I think we are still experiencing, is about connecting people – the social era.

Here’s an essential point: It is not access to information, but access to each other that is going to make all the difference, in every industry, including health care, in the coming decade. Seven in ten U.S. adults use social platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn.

The early stages of the internet cracked open the funnel of information and allowed it to flow more freely to the people who need it. How might we expand on this? How might we recognize the experts who are not on any research institution’s organizational chart but who have wisdom to share about clinical trials? How might we listen, respectfully, to patient and caregiver voices on social media?

The upward trajectory of these trend lines make change seem inevitable. But there is still resistance to using all the tools available to us, both on the part of professionals and lay people. We should not be surprised by this hesitation. After all, social media may seem alien to them. To quote Alan Kay: Technology is anything invented after you were born. People judge the present using yardsticks of the past. They need to be convinced that social media is key to their work. Let’s forgive them, because we are kind. But let’s change their minds.

Learn more about the National Cancer Institute‘s event, “At the Crossroads of Social Media and Clinical Trials: A Workshop on the Future of Clinician, Patient and Community Engagement.” Symplur captured the tweets or you can search for #ClinicalTrialsSM on Twitter. The video from both days of the event is available on the NIH site and all the presenters’ slides are now online, too.

Featured image: Train, Weiz 2017 by ::ErWin on Flickr.

1. Thanks for the new source for “17 years.” I’d only had Balas & Boden’s. But I decry the insider perspective on the complaint in your link: “This effectively ‘blindfolds’ investment decisions and risks wasting effort.” WTH, people – how about noting that it delays sick people getting the treatments??

(…which in turn is just one way that e-patient communities can kick the snot out of traditional care, if people are smart enough to ignore “Stay off the internet.”)

2. You packed a gold mine into that Liz Salmi tweet. Everyone, PLEASE go read the thread (perhaps including the linked-to blog post by lung cancer patient Lisa Goldman about the ignorance of some researchers about her disease).

3. I’m re-“ear-reading” Cluetrain’s 10th edition, because I’ve been working on a healthcare Cluetrain book – probably not 95 theses, but a similar batch of aphorisms that people who want to get a clue should get serious about, because the ones who don’t want to are indeed truly missing the train. And as you say, it’s a serious shortfall when authority is significantly out of date.

Which takes me back to our exchange in Nov 2012 that mentioned Cluetrain’s description of how all the old boundaries had fallen apart. That includes the supposed boundaries of what information should be sought out.

Hooray! You and I share a love of the hunt for good evidence, so that makes it all the better to share a truffle 🙂

And yes, it’s been 6 years since that conversation about boundary-breaking and for better or worse we need to keep it going.

> for better or worse we need to keep it going

A smart-aleck would note “Hey, 6 is more than a third of the way to 17!”

I lost all patience for the humor in that, though, when I started thinking how many people can die or suffer in each of those lag years. Doc Tom was spot on when he called it “the lethal lag time.”

How will this help me?

Roger, can you tell us more about what you are working on or dealing with?

Agree, it’s time for these larger institutions to start using social media more often and more effectively. Our society is now on the platforms in such high magnitude it makes sense to use the communication medium.