Here’s a lesson I learn over and over again: Never assume knowledge. Don’t waste your time making a point if you are not sure your audience understands the context for it. Or, as the wise Andy Kohut used to say, “If they don’t get the premise, they won’t get the joke.”

Last year I spoke on a panel about health data interoperability. My co-panelists and I were asked to explain why health insurance companies should invest in the changes required by the federal government’s new “final rule.” On stage, we used plain language — no acronyms, no jargon — and I even found a way to talk about sandwiches and whisky to try to bring the concept home. I thought we did a great job.

A friend came up to me during the break, however, and said, “I’m sorry to tell you this, but nobody at my table understood your panel. Someone actually turned to me and said, ‘What was that all about?'”

It is in that context that I urge you to read and share an excellent new report by my colleagues Rachel Tunis and Christine Bechtel: Leveraging Data-Driven Patient Participation to Accelerate Medical Research (FasterCures, Milken Institute; 2020).

From their introduction:

The fuel for biomedical innovation is data, and today we are generating more health and lifestyle-related data than ever before. These datasets hold enormous promise for biomedical research because they can be combined and analyzed using technologies such as artificial intelligence to produce new insights essential to improving overall health, building our understanding of disease causation, and potentially discovering new treatments and cures. Data-driven patient participation—the ability for anyone to contribute their health information such as electronic health record (EHR) data, biospecimens, and wearable data for research—has emerged as another tool for research entities seeking to make discoveries that advance medical research and improve care for patients. Further, it directly involves patients in biomedical research, allowing them to help speed its progress in disease areas that they care about, and helps patients engage in and have more control over their health care, which is known to improve health outcomes.

Tunis and Bechtel go on to make the case for why everyone — researchers, clinicians, citizens, policymakers — should not only understand but embrace these new opportunities to involve patients in the pursuit of answers. To convince people, they lay out the promise and the challenges (such as gaps in existing patient privacy regulations, lack of interoperability, and under-representation of historically marginalized populations, to name a few). And they profile five pioneering organizations: the All of Us Research Program, Fight to End COVID, PatientsLikeMe, Tidepool, and War on Cancer.

To those of us who have been working on this frontier for years, it’s a “well, of course” assertion to involve patients. But that’s why I love their report: We are not their audience. We are geeks. They are trying to reach (and teach) the mainstream.

Please click through to read the report (a 12-page PDF). Share it with all those who nod their heads but secretly aren’t quite sure what you’re going on about all the time when you talk about data-driven patient participation in medical research.

Disclosure: I am an advisor to FasterCures.

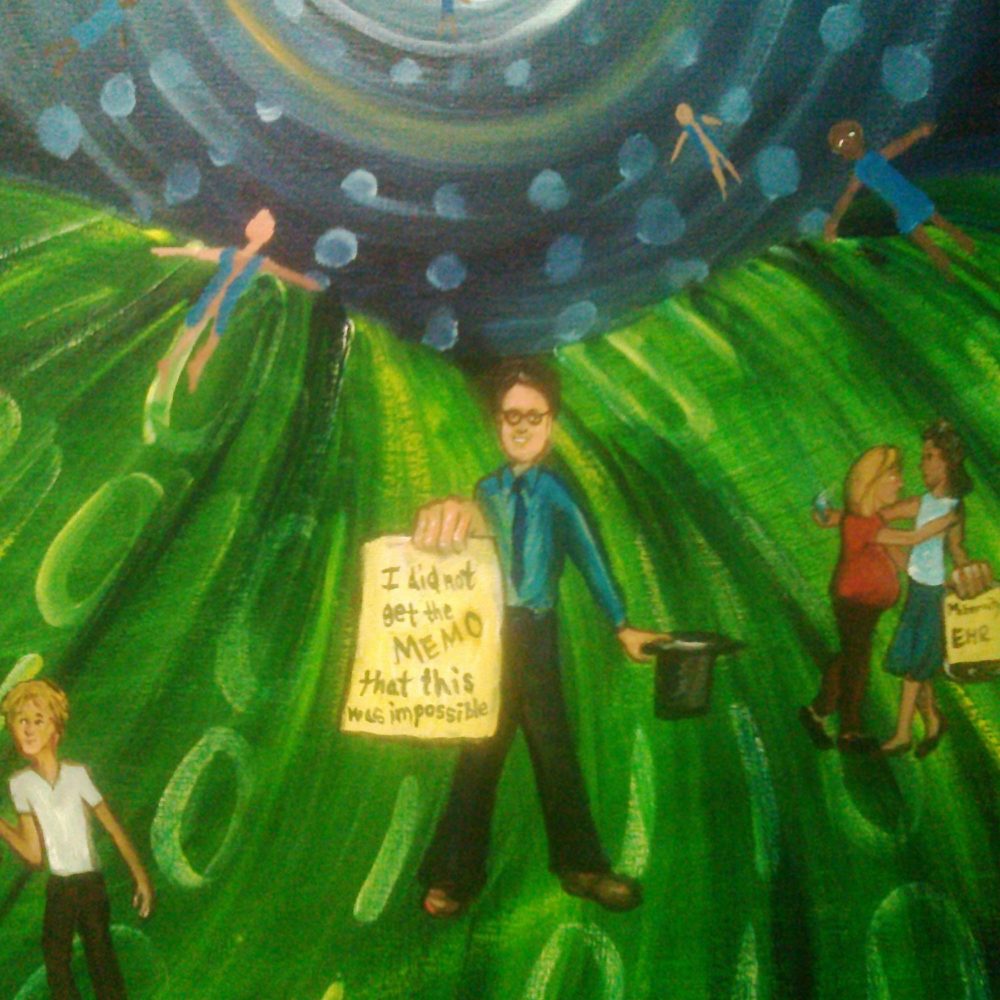

Image: “What Todd started,” by Regina Holliday (2012). Description: A painting of a person holding a sign that says, “I did not get the memo that this is impossible” near two people embracing over a second sign that reads “Maternity EHR” as 1s and 0s race by underneath the scene. Todd Park, the first Chief Technology Officer for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in the Obama Administration, helped start a data liberation movement that continues today.

This is such an important point. Data fluency, data literacy, data confidence, data justice, data feminism…call it what you want (and tailor it to your audience), but it’s critical to advancing change in every sector. I wrote about this recently for Meeting of the Minds (https://meetingoftheminds.org/data-fluency-is-an-antidote-to-fear-and-apathy-33538). And, it’s a frequent topic among members of the Data Visualization Society (on their Slack channel).

Mary, I love your post! Thanks so much for sharing it.

You’re right: We are asking too much of people, throwing gobs of COVID19 data at them without being clear about the context, the background, the basics of how to interpret these numbers.

On a personal note about COVID19 data:

My mom’s retirement community sends a daily email with an update on the number of suspected and confirmed cases among residents and staff. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services recently required such facilities to start reporting their cumulative numbers and it MASSIVELY improved the daily reports. I had been trying to do the math in my head as we went along — i.e., how many confirmed cases have there been? This number is going down, is that because they got better? The cumulative numbers bring the picture into focus.

Here’s a link to the PDF of the CMS announcement.

Great post on this important issue. Will read the full report.

I think that the NIH AllofUs Research program is a great example of donating data for research. Also, the new Scripps, Stanford working with Fitbit to assess wearables’ COVID-19 tracking abilities https://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/scripps-stanford-working-fibit-assess-wearables-covid-19-tracking-abilities

Thanks, John! I’m going to add that study to my other post, Tracking the trackers. And yes, it was difficult to narrow the list to just five pioneers in this area! Each one is emblematic of a category (and there are more categories, too).

Your posts – including their tweets – continue to evolve into works of art, both in the visual sense and in the way they form compositions that resonate on different channels. It was hard NOT to stop my trip to the treadmill and go read.

I want to add that my own sense of mistrust is about a kind of knock-on / follow-on problem: commercial data engines that are downright sloppy with the inferences they sell to employers, police depts, etc. They’re unregulated, opaque, inscrutable, as related by data scientist and former Wall Street quant Cathy O’Neil told in Weapons of Math Destruction. I hope the project(s) will take seriously the challenges added by downstream parasites like the companies she describes.

Having said that, after a decade (as you know) doing this work, it’s a thrill to see what has moved forward (not least how that “final rule” realizes part of what we strived for) and to see how friend Christine continues to shine, both in her own work and in lighting the way forward. May she continue to succeed!

btw, regarding “Never assume knowledge” – I don’t know the situation of that event, but the only problem that can trap us as speakers is if the event host (who preps us) is totally out of touch with his/her audience and THINKS they already know things that they don’t. It really irks me, so I’ve learned to always toss in at least the briefest touch on the topic.

But man it makes me mad when I bust my butt to be relevant and I get misled. :-/ So yes, never assume knowledge.

Hooray for Christine indeed! And if you have not yet met Rachel, you’ll root for her, too.

The event organizers knew that we’d be pushing the thinking for many people in the room that day, which is why we were careful to create talks that were as jargon-free as possible and related directly to their possible concerns, but in retrospect we should have left more time for Q&A. Maybe then we would have been able to hear a brave person speak up to say, “Tell us again why we should care about this?”

Q&A is when the power dynamic shifts, I think, and the audience gets to push back on the agenda being forwarded by the speakers or the event organizers. It’s always been my favorite part of public speaking (just as the comments section is my favorite aspect of my blog, come to think of it.)

Contemplating this post, “never assume knowledge” hit me twice in different ways, both sobering. I’ll put them in separate comments.

It’s 11 years since I got involved with these cultural conversations, and for a long time everyone I talked to knew what I was talking about (re patient empowerment, patient engagement, patient communities, patient data access). Not so much, anymore: I keep being asked to explain my Google Health story – discovering that my hospital’s records contained all kinds of errors and ridiculous junk, discovering that they had no clue how to manage data carefully, discovering that US medical insurance billing is riddled with folly, and the genesis of “Gimme My DaM Data (“Data About Me”) because you guys can’t be trusted with it.” (See, there I forced myself to not assume knowledge: I said more rather than just “my Google Health story.”)

And I keep having to explain the principles that Doc Tom Ferguson was writing about 20 years ago – nobody knows everything, patients truly can find valuable information, it helped save my life, etc. Ultimately I realized (duh) that healthcare is a big industry with LOTS of people coming and going, and if someone has been in the industry today with a full five years of experience, they weren’t around even at the end of the computerization program from 2010-2015.

Not only that, there are MDs now who were in high school when that happened, not to mention people in industry. The irony is that since I was so innocent and new to healthcare back then, I was accustomed to needing everything explained to me. But now it’s my turn to never assume knowledge.

The other has nothing to do with healthcare, and it saddens me. It’s a separate dimension of “never assume knowledge.”

A lesbian friend in my age group, a long-ago veteran of the LGBTQ culture wars and a dedicated hospice volunteer in the HIV/AIDS pandemic, says she’s seeing lesbians humiliated, mocked and scorned … by young gay men, who evidently have zero awareness of the years of sacrifice and culture wars that went into creating their relative freedom to express their identity – and especially the underlying principle of respecting each individual.

In this sense “never assume knowledge” has broader societal implications than effect conference speaking; it underlies all effective communication.

And I’ve never been clearer about why religions and other societal structures have creeds and stories that are taught to the young.