In the spirit of Public Q&A, I am sharing a question I received from someone who helps run outreach and support programs for a disease-focused nonprofit:

“In your research did you learn about what mode and types of connecting teens preferred? Did any teens express wishes for something online that they couldn’t find in terms of connecting with peers?”

Essentially, what is missing? How can we better serve this age group that is likely to be online daily?

I will share my answer and I am hoping that other people — researchers, clinicians, community leaders, and teens themselves — will add their ideas in the comments. Let’s help this organization and others like it!

To begin, I’ll quote from the Hopelab/Well Being Trust report I co-wrote with Vicky Rideout: Digital Health Practices, Social Media Use, and Mental Well-Being Among Teens and Young Adults in the U.S. :

Teens and young adults turn to each other for advice when making all kinds of decisions – including those related to health. Previous studies have shown that about two in ten U.S. adults have gone online to find people who might have health concerns similar to theirs. This study shows that youth lead the way in the social revolution that is underway in health.

About four in ten (39%) young people say they have gone online to try to find people with health conditions similar to their own. Most of those who tried to find such “health peers” online reported that they did succeed in finding them (84%). This means that, across all survey respondents, a total of 33% of young people have successfully found health peers online. Almost all (91%) of those who found health peers online say the experience was at least “somewhat” helpful: 20% say it was “very” helpful and 71% say “somewhat.”

This person is asking specifically about teens though, so I’ll note that just 25% of 14- to 17-year-olds say they have tried to find health peers online, compared to 51% of those ages 18- to 22-years-old.

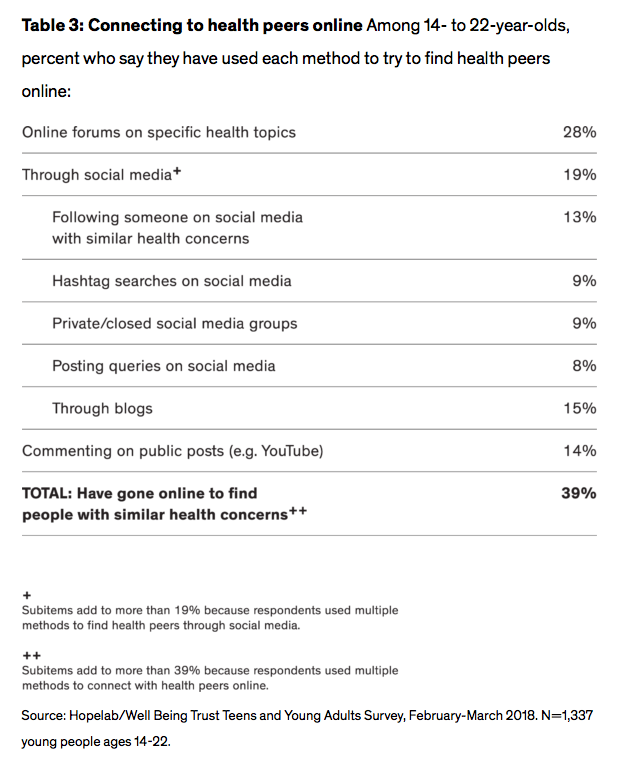

If someone answered “yes” to “Have you ever gone online to find other people who might have health concerns similar to yours?” they were also asked, “Have you ever tried any of the following ways to find people online with health concerns similar to yours?” The table below lays out all the strategies we included and the percentage of young people who said they tried each one:

This table is an illustration of how difficult it can be to design survey questions about a fast-moving topic. We didn’t include, for example, any questions about how someone might use an app to connect with a health peer. There are probably many more ways that a teen might look for and find someone who shares their health concern, which is why this research is a useful but incomplete guide. Interviews and focus groups with people in the target group, for example teens living with a certain condition, will be essential to understanding their preferences.

We also asked why young people why they HAVE NOT looked online for a peer:

Of the 61% of those who say they haven’t sought out people with similar health concerns online, most say it’s because they simply haven’t had any serious health issues (55%; respondents were allowed to select multiple reasons why they had not done so). But many also say they would rather talk to people in person (36%) or that they prefer to rely on professional health providers (33%). One in four (25%) say they don’t trust online advice from people they don’t know. Fewer than one in ten (9%) say they don’t know how to find people online with similar health conditions.

That last sentence is important. It means that only a tiny group (about 5% of 14- to 22-year-olds) say they don’t know how to find health peers online. It’s a ripe moment for peer to peer connections. Young people are feeling confident that if they do have serious health questions and decide to supplement the advice of their clinicians, they know how to look online for a “just-in-time someone-like-them.”

It’s also important to note, however, that when we asked people to elaborate on their answers to this question, teens wrote about how their parents would not want them talking to online strangers about personal issues. For some teens, it may be important to get their parents’ approval before venturing into an online forum.

In a separate question we asked young people who have looked online for health peers to tell us, in their own words, what happened:

“I have type 1 diabetes and tried to find a group of teenager type 1’s on Facebook. I did. It was cool. Made some friends.” – 14-year-old male

“I found a very good friend in another country that had the same condition as I did, and it was truly inspiring to have the freedom to tell them about it and likewise them to me!” – 21-year-old male

“I went on a chat forum for people with eating disorders. I made a friend that I keep in touch with. We talk about what we have been eating recently and how we have felt about our situation.” – 15-year-old female

“I shared my experience with IBS [irritable bowel syndrome] on Facebook and gave tips [for] major flair ups.” – 22-year-old female

“I wanted to know something about birth control and people had the same questions and it helped me know that I wasn’t alone.” – 21-year-old female

“I read someone’s [story of their]… recovery [from] trichotillomania [pulling out one’s hair] and found it inspiring and relieving that I wasn’t the only person experiencing this compulsion since childhood.” – 20-year-old female

“I shared my scoliosis journey and spinal surgery and updates on post-surgery recovery.” – 20-year-old female

“I have watched several people detail their fitness routines and how they used it to beat mental health disorders such as body dysmorphia and those affected by obesity and food addiction.” – 22-year-old male

“I’ve watched several videos that are first person accounts of coping with depression and anxiety. I can’t give specifics, because there were a few separate instances and all were not very memorable. It was about finding a sense of ‘I’m not the only one’, not about finding out about a specific person’s struggle.” – 22-year-old female

There were hundreds of responses that did not make it into the final report, so I went back into the data and found more quotes that shed light on the “what’s missing?” question:

A 15-year-old boy wrote, “Forums are very helpful to read and learn about other people who are facing similar things. The only downside is that there is no way to know if what they are saying is true or not.”

A 16-year-old girl wrote, “There is a support group for my family’s mutation. This particular support group discusses how to achieve the proper diet for the mutations along with supplement info. Unfortunately, most people on the site don’t know much about how to get help. Therefore, after my mother learned how to help the whole family she still continued to share her knowledge with the group. She even met some people who were able to help her with other problems.”

How might an organization address these issues of fact-checking, knowing who is telling the truth (and who is not), and ways to connect online forum members with additional resources?

I also found quotes about how online research and connection to a just-in-time someone-like-you can make all the difference:

A 20-year-old woman wrote, “As a young teen I always felt there was something wrong with me. Went online for answers and found information about depression and anxiety specifically and felt it applied to me. It helped in that it pushed me to go see a therapist who referred me to my psychiatrist who ended up diagnosing me with bipolar disorder. Educating myself on these mental health issues helped me get the treatment I needed.”

A 17-year-old boy wrote, “Wanted to find out more about EDS Foundation and others who suffer with the disorder.”

Now I’m turning to you, my community colleagues: What do you see in the field? How might a condition-focused organization attract teens to online communities? Please share your thoughts — and other questions — in the comments below.

Featured image: Subway in Munich, Germany, by Chris Yunker on Flickr (because to me it illustrates our worry about a “missed connection” among teens online).

Thanks to Patient Critical Co-op who tweeted this gem:

“Youth trust texting & online communities more than any other demographic-but they also see the risks that come with anonymity.

We talked with @KidsHelpPhone about adopting texting for crisis intervention & how it changed their work: Alisa Simon: Kids Help Phone & Digital Health”

I’m listening to the interview now and it is full of useful tips and insights. Here’s one: among the young people who texted for help, when asked if the text support was NOT available, what would they have done? 79% replied that they would not have reached out to any other service or resource. They would have tried to ignore the problem they were having. 7% say they would have gone to the emergency room.

Highly recommend listening to this audio interview if you can.

I think two issues for teens seeking health advice are mental health issues (including suicide) and sexual health. Peer support can be tricky because of the potential for misinformation that might be shared. However, there is the opportunity for teens to talk freely among peers which they may not feel comfortable discussing with adults or healthcare professionals. Perhaps one solution is training peer moderators for such communities.

Thanks, John. I appreciate this prompt to go back to the data that we collected but didn’t have room in the report for: the differences between the teens vs. young adults when it comes to looking online for information about certain health topics.

Again, the data below was collected in Feb-March 2018 for a study sponsored by Hopelab and Well Being Trust. Here’s a link to the methodology for more details. When I write “teens” I’m referring to 14-17 year-olds. When I write “young adults” I’m referring to 18-22 year-olds. All of the differences below are statistically significant.

26% of teens say they have gone online for info about depression, compared with 49% of young adults.

Info about anxiety: 28% of teens vs. 54% of young adults

Info about diet and nutrition: 41% of teens vs. 62% of young adults

Info about eating disorders: 12% of teens vs. 24% of young adults

Info about birth control: 18% of teens vs. 40% of young adults

As you can see, teens are less likely than young adults to go online for health info in general. But when they do, if they are looking for peers, how might organizations support them, meet them where they are, and get them the info they need?

This data is very interesting to me as the founder and ED of a nonprofit supporting female-identified students through their postsecondary transition into whatever comes next. According to the study’s definition, these are young adults. They are often steering their own way because of a lack of adult guidance or adult knowledge. (Many of our students are first-generation college students and from immigrant or low-income/no-income families.) Trauma they’ve experienced or have been exposed to leads them to seek out emotional and behavioral health services, but they’re stymied by where to turn, how to pay, what’s right for them. Working through organizations (for profit and nonprofit), brands, and personalities teens and young adults trust and are already in contact with is one way to expand their ability to access trustworthy, reputable, and reliable info.

HopeLab was one of the first NPOs in the young adult cancer space that I encountered long before I found my own voice as a then 8-year cancer survivor (and 2 years prior to founding Stupid Cancer) They were still in the “CD-ROM” stage of Re-Mission exactly during the time of when the nascent young adult cancer movement was coalescing through LIVESTRONG. I was so inspired by their work that, even now — 14 years later — the partnership established with SC continues to help them evolve their mission and more effectively serve their audience. Their data is remarkable despite the Herculean effort of wrapping our heads around Gen Z’s behaviors with, through, and, hopefully, beyond a diagnosis of cancer.

As some may know, I founded Find Your Ditto on the premise that social connections are critical to chronic health burnout/wellbeing. Susannah has been a fabulous resource for all things on the topic, though I do have over 20 years of personal experience living with chronic conditions {starting at age 4}.

When I was growing up, the internet boomed and my mom got me onto some message boards {for example, through the American Diabetes Association}. I am still close friends and in contact with one girl I “met” almost 15 years ago on a board, and yet we’ve never met.

My mom benefitted from the boom of listservs, particularly in the celiac disease community, to share experiences parenting and resources for food/travel/etc, before the gluten free fad took over {which has been a detriment to celiac patients, in my opinion}.

I know that teens are looking for others online– I built a business based on it! — yet it’s still of interest to determine whether the key element is the social connection to avoid the “it’s just me” “I’m alone” feelings or more to treatment information. In my experience, there is a shift around teenage-hood that includes a growth in information seeking as young people with chronic conditions are transitioning into adult care/more involved personal care as their parents transition out.

I still hesitate to direct newly diagnosed people to information on the internet, because of the wide dispersal of misinformation, including a lot of “naturopathic cures” etc. {there was a recent case of a death of a type 1 diabetic child because the parents met a naturopath who told them the child didn’t need insulin, just natural compounds}. I do, however, connect people to others in the community that I trust for common bonds/friendship, which I know personally has been critical to my wellbeing living with chronic conditions for so long.

Just my two cents. Happy to chat more!

Thanks for this important blog post. It’s especially relevant to me as the cofounder and CEO of Project HEAL (https://www.theprojectheal.org/), the largest grassroots community of patients with eating disorders. Last year, we launched Communities of HEALing, one of the first peer support and mentorship programs for people with eating disorders. The need for this program came directly from our community: when we asked our 100k member community what made the biggest difference in their recovery, they answered loud and clear: other people who had been there.

The issue of trustworthy information and support is a very critical one. Especially in the eating disorder field, peer support has lagged behind other mental illnesses, largely because people have been worried about relapse and the potential for people with eating disorders to trigger one another. This is a real concern. In response, our program is defined by rigor. Our volunteer mentors are vetted to ensure that they’ve been in a strong and active recovery for at least 2 years, undergo a rigorous training (35 hours over 7 weeks), and receive ongoing supervision.

As we’ve scaling, we’ve received pressure to lessen the rigor of our program, but have never budged, as we truly believe it is the secret sauce of our program.

What Research Tells Us About Online Support Preferences of Youth

Youth desire sites independent from their social media for getting support for illness:

Youth access the Internet strategically and differentiate what sites they use to socialize and have fun from those they seek out for support and information about illness. While youth report using social media sites, such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to stay connected with family and friends, these sites are likely not the best place to reach them to provide information and support regarding illness, whether mental or physical (Ahola Kohut et al., 2018; Wetterlin, Mar, Neilson, Werker, & Krausz, 2014). Adolescents report preferring to keep their illness private and tend to present themselves as “average” or “healthy” on their main social media sites (Van Der Velden & El Emam, 2013). In a survey of 17-24 year olds, most (77%) stated they would be unlikely or very unlikely to use social media sites during a difficult time (Wetterlin et al., 2014). However, youth expressed a desire to connect with others with shared experiences who could relate and understand their situation (i.e. similar diagnosis) as a form of social support (Ahola Kohut et al., 2018). Thus, providing youth with a separate, confidential space to seek support and information about illness is key to engaging youth in such support.

Support should come from peers and professionals:

Support provided by both health care providers and peers is desired, as medical professionals will ensure that information shared is medically accurate and peers can provide more experiential, hands-on knowledge and support (Ahola Kohut et al., 2018). Adolescents are very aware that all information accessed on the Internet is not of the same standard of quality and want to avoid misinformation, thus preferring that medical professionals are available to vet posted information (Ahola Kohut et al., 2018). Moderated discussion forums add reassurance of safety, helpful suggestions, and comments to “fill the silence” and stimulate discussion among participants (Nicholas et al., 2012). Additionally, space for off-topic conversations should be provided, as adolescents want to develop social connections related to their “whole self” and not just disease-specific support (Ahola Kohut et al., 2018).

Where possible, merge online and in-person support:

Hybrid support groups, linking brick and mortar structures with online support programs, may offer unique benefits (Treadgold & Kuperberg, 2010). Adolescents would like the opportunity to meet people from their online support networks in real life where possible, potentially in the form of organized events that occur outside of healthcare settings (Ahola Kohut et al., 2018; Treadgold & Kuperberg, 2010). These meet-ups have the potential to strengthen the relationships made online and vice versa. Additionally, some programs use face-to-face meetings with healthcare professionals to invite and screen potential participants for online groups, engendering a sense of security about the veracity of the support and information provided online (Treadgold & Kuperberg, 2010).

Support sites should combine aspects of websites, apps, and peer mentoring programs:

Youth desire varied methods to access reliable information and make social connections. Sites should be accessible via computer and smartphone. Desired features include reliable, up-to-date information; links to trusted resources; private messaging between users; group chats and/or video calls; message boards where people can pose questions for other users and/or medical professionals; ability to connect with others “like them” (i.e. age, disease, etc.); personal profiles; and ability to post photos and videos (Ahola Kohut et al., 2018; Nicholas et al., 2012).

Megan S. Evans, MS

Peers for Progress (peersforprogress.org)

Department of Health Behavior

Gillings School of Global Public Health

University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill

References

Ahola Kohut, S., LeBlanc, C., O’leary, K., McPherson, A., McCarthy, E., Nguyen, C., & Stinson, J. (2018). The internet as a source of support for youth with chronic conditions: A qualitative study. Child: care, health and development, 44(2), 212-220.

Nicholas, D. B., Fellner, K. D., Frank, M., Small, M., Hetherington, R., Slater, R., & Daneman, D. (2012). Evaluation of an online education and support intervention for adolescents with diabetes. Social Work in Health Care, 51(9), 815-827.

Treadgold, C. L., & Kuperberg, A. (2010). Been there, done that, wrote the blog: the choices and challenges of supporting adolescents and young adults with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28(32), 4842-4849.

Van Der Velden, M., & El Emam, K. (2013). “Not all my friends need to know”: a qualitative study of teenage patients, privacy, and social media. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 20(1), 16-24.

Wetterlin, F. M., Mar, M. Y., Neilson, E. K., Werker, G. R., & Krausz, M. (2014). eMental health experiences and expectations: a survey of youths’ Web-based resource preferences in Canada. Journal of medical Internet research, 16(12), e293.

Megan, thank you for this epic & awesome comment! I will share it with the person who asked me the question originally and it will live on as a resource — much appreciated.