How might we empower people to participate in research about their own diseases or conditions?

Which models work best for organizations solving medical mysteries or improving care for those living with rare conditions?

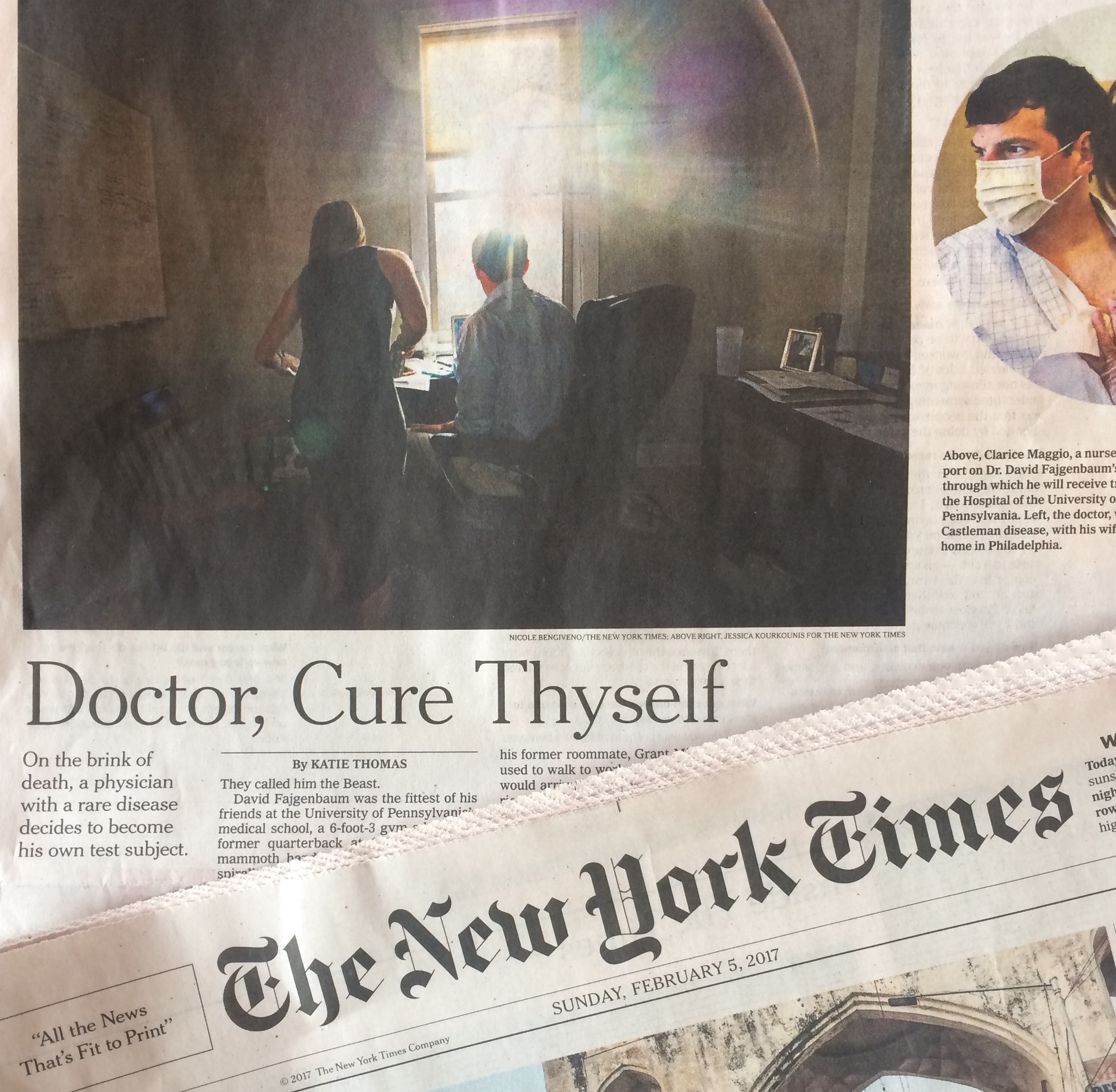

These are two of the questions raised by a New York Times story today: “His doctors were stumped. Then he took over,” by Katie Thomas about David Fajgenbaum, MD, and his quest to solve the mystery of Castleman disease.

Here is the section that jumped out at me:

In medical research, discoveries come slowly and take twists and turns that no one saw coming. Seasoned researchers have learned to rein in their optimism and to know that true breakthroughs can take years, if not decades, to realize. Not Dr. Fajgenbaum.

“I almost wish that every disease had a David to be a part of the charge,” said Dr. Mary Jo Lechowicz, a professor at the Emory University School of Medicine, who has studied Castleman disease and serves on the network’s advisory board.

Dr. Fajgenbaum’s single-minded mission to take on his own disease is also typical of the rare-disease world, said Max Bronstein, the chief advocacy and science policy officer at the EveryLife Foundation for Rare Diseases in Novato, Calif.

“A lot of mom-and-pop patient organizations emerge to take on these huge challenges in rare diseases,” he said. “I don’t think there’s one correct model for each disease; there’s been so many different approaches.”

Who does David remind you of? That’s the first question that I’d love to see discussed in the comments below. The people who sprang to my mind:

- Jamie Heywood and his brothers, who started PatientsLikeMe

- Julie Flygare, founder of Project Sleep and an advocate for narcolepsy research

- Catherine Fairchild and Laurie Strongin, mothers of boys with two different rare diseases

- Gilles Frydman, who started ACOR.org and then Smart Patients, with Roni Zeiger

- Erin Moore, who is working with the C3N Project and other organizations on behalf of people living with cystic fibrosis

- Matt Might, a rare-disease dad and geek extraordinaire who helped identify NGLY1 deficiency

- And thousands more…

Again, let’s discuss: How might we empower more people to become active, expert participants in research about their (or a loved one’s) disease or condition? What are the factors that lead to someone’s empowerment?

The extra advantage that David has, as pointed out in the story, is his MD and affiliation with Penn. An interesting study might be to show the differences between organizations with medical professionals leading it vs. those with the “honorary PhD” that rare disease patients and caregivers often earn.

Another aspect I’d love to hear more perspectives on: The relative advantages of the different models of organizations. Three models comes to my mind: The “mom-and-pop” nonprofit vs. those sited at an academic institution vs. one that is corporate-backed, for example. Alternatively: Models for change also take different paths, such as community-building vs. data- or specimen-collection as the primary focus.

By the way, if you are new to these questions: Welcome! Some background:

Participatory Medicine is a model of cooperative health care that seeks to achieve active involvement by patients, professionals, caregivers, and others across the continuum of care on all issues related to an individual’s health. Participatory medicine is an ethical approach to care that also holds promise to improve outcomes, reduce medical errors, increase patient satisfaction and improve the cost of care.

If you’re ready to dive in, I’m sure there are other questions to discuss beyond the ones I list above. Please join the conversation on Medium or post a comment below.

Leave a Reply