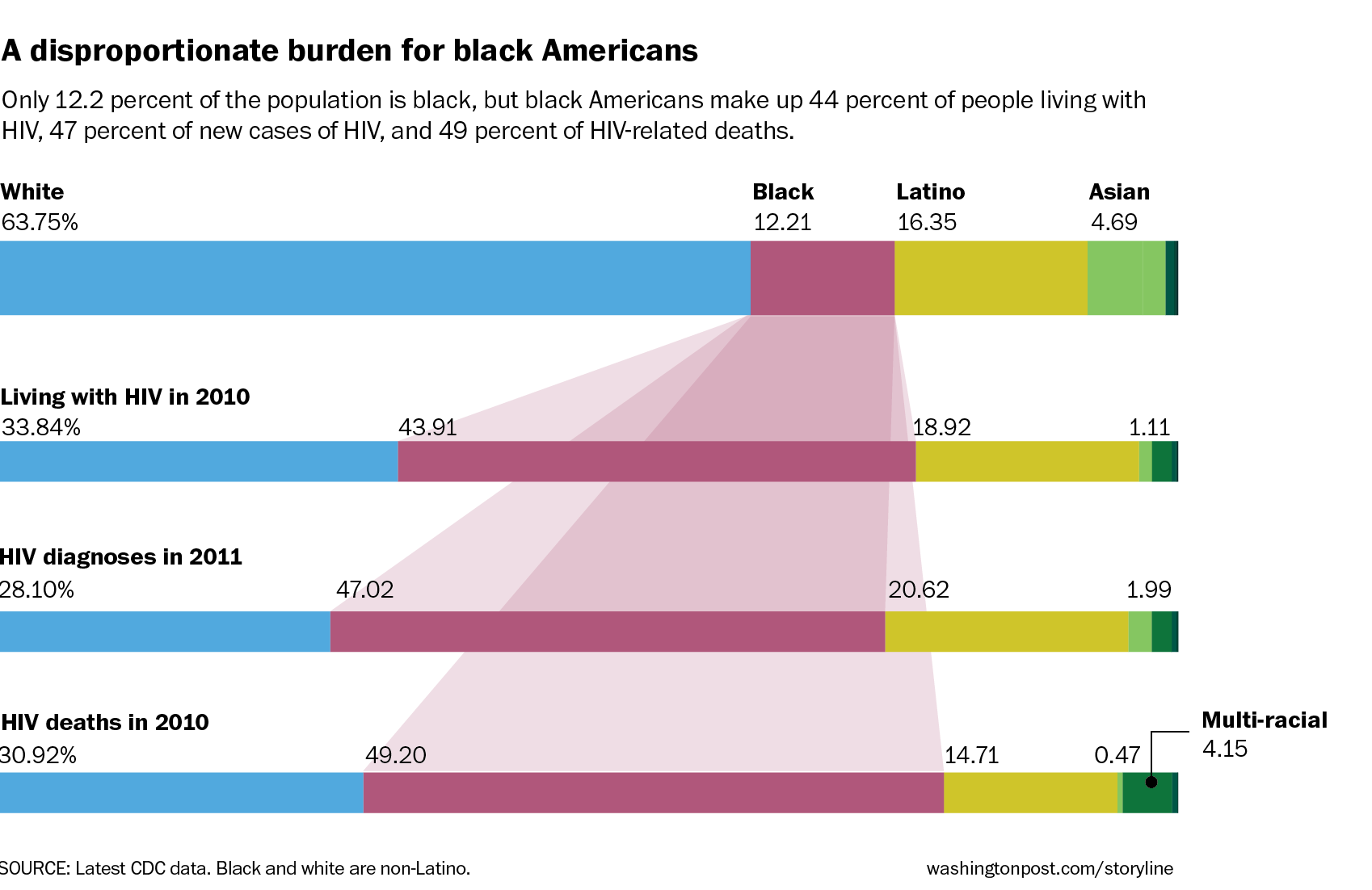

Take a deep breath and then look at this data about HIV in the U.S.:

I have seen these numbers before, but never laid out so clearly and so beautifully. Thank you, Jeff Guo of the Washington Post, for breaking my heart. Thank you, because I think we all need our hearts broken anew from time to time. We need to face the reality of the epidemic. We need to look in the mirror, wipe away the tears, and see ourselves clearly in order to start making plans for change. We need to visualize health in order to communicate and pursue it.

And yet:

“We’ve known for over 50 years that providing information alone to people does not change their behavior.” – Vic Strecher, quoted in a fabulous article by Jesse Singal titled, “Awareness is Overrated.”

So what will? What can make people change their behavior?

I think advice and information delivered by a “just-in-time someone-like-me” holds promise. And we have the ability to connect in our hands.

We are all asking secret questions online — even more so when we use our phones. People who search the AIDS.gov site on their phones, for example, use much more specific terms than those who search from a desktop or laptop.* Mobile seems to make things personal, immediate, and specific.

What if all the knowledge and insights being found privately could be shared more widely? Not everyone is ready to have words like “vagina” and “anal” pop up on their Facebook page, but what if there was a way to bring frank, truthful talk about sex to people’s phones, one-to-one, one-to-many, or many-to-many? What if we could unleash the power of science, storytelling, and sharing? What if we could make health information relevant, in the moment, when we need it, like a heartbeat, a deep breath, or a caress is relevant?

Who knows better than someone like me how to break my heart, make me laugh, and get me to change?

Other sources of inspiration, which I need today after seeing that data:

- Love Heals

- Bedsider

- Harm Reduction’s videos

- Metro TeenAIDS

- Kicesie’s Sex Ed videos

- Remarks by Gina Brown of the Office of AIDS Research at NIH, including the immortal question: “When a woman stands up, which way does her vagina point?”

* Source: Cathy Thomas of AIDS.gov, at a meeting of the Federal HIV/AIDS Council in 2012.

Featured image: Give – Take – Care, by Jessica Hagy.

Thanks Susannah, This is one of those columns one needs to carry around when some people insist racism and inequality are not at the center of the healthcare and health equations.

Absolutely right. It took my breath away.

The fact that medicine has advanced to the point that we now have innovative, personally customized drugs and drug cocktails for diseases like HIV and Cystic Fibrosis that are dramatically improving and lengthening lives, and yet people are still dying/suffering from these very diseases merely due to a lack of access (or other structural or motivational barriers) — it breaks my heart too, and, to be honest, it disgusts me.

We can and must do better.

The personal and societal barriers are very real — I understand that — but I just have to believe that if we can create drugs that are personalized to individual genomic and molecular characteristics of disease, if we can achieve that kind of stupendous research feat in the lab, then we MUST be able to apply the same ingenuity to the barriers that are preventing access and behavior change for so many in the US today.

Here’s another heartbreaking example:

http://online.wsj.com/articles/costly-drug-vertex-is-denied-and-medicaid-patients-sue-1405564205

Emily, that is a heartbreaker. This quote, for example:

If Chloe had been given Kalydeco in 2012, “we probably would’ve avoided most of the hospitalizations, if not all of them,” said Dr. Schellhase.

I mean…I just…no words.

Susannah, thank you for writing this. I was a peds HIV clinic nurse during part of the “hiatus” I took from QI work to go to nursing school and get hands-on, touching-and-caring-for-real-patients experience.

>90% of the kids with HIV we followed were black and many, many of them were in such desperate social situations that learning about risk, taking meds, etc were truly the lowest priority in their lives. But they were on their phones nonstop, even during clinic visits. And the one time a year that many did connect at camps for kids with HIV, you could just see the hope that emerged (I will add the link to these wonderful camps when I dig it up). They could see their future for a bit, but then often got mired back down into the day to day. However, they did continue to connect with their new friends (the ones who knew the secret that anchored them down) on Facebook, as if they were lifelines for one another back in those chaotic lives.

So there is huge untapped potential here. I’ve been away from this work for about 2 years now so thank you for prompting me to reflect. I have many more thoughts and ideas re: this that I will add as they gel. Thank you for getting the wheels spinning!

Thank you, Sarah! I love that I helped get your wheels spinning. Please come back and share more when you have time. And I’d love to learn more about those camps.

P.s. For these kids, What if “one pill once a day” (for those who can take that amazing regimen) + “use condomns every time” was made as easy as it sounded? #Whatifhc

Neal Ulrich has a great suggestion: to turn our What if health care… dreams into How might we… conversations. As he points out, HMW has the potential to be more open, less accusatory or complaining (not that all or even most of our What if questions have been, but I see his point).

As he writes: “Instead of suggesting 1 strategy to improve healthcare, #HMW starts a more open-ended discussion with possibly 12s of solutions” For example: “Hospitals are so noisy” becomes “#HMW decrease noise & improve patient/fam privacy?”

So: How might we make “use condoms every time” an easy, natural habit for these kids?

Both “how might we” and “what’s stopping us” are good approaches, especially when combined. Applying some basic QI tools like failure mode analysis may seem a strange fit for this particular challenge. But why not? I bet you could rally a whole lot of people to work on it together! What are the steps in the process, what can go wrong, and what can be done to mitigate each thing that can go wrong?

Maybe we need a whole lot of crowdsourced (and I mean big crowds!) FMEAs to tackle some of the brilliant whatifhc ideas that are percolating! So instead of just dreaming together, making the “how” part more concrete.

Also, here is the camp: http://safehavenproject.org/programs/camp-safe-haven-north-carolina/

Of course this is searing to read about and hard to even think about.

Strecher’s point about “50 years ago” gives me backup for my assertion “information alone doesn’t change behavior.” I’d like to know his original citation on that, but heck, anyone who’s watched the decades of efforts to stop tobacco use knows that facts alone don’t do the job.

I read somewhere recently that what got people to brush their teeth, a century ago (?), wasn’t facts about decay, it was ads about “yellow film” on the teeth. Basically, social pressure. And someone said that among the most effective anti-smoking ads were ones that showed teens what smokers’ skin looks like in their 50s and 60s.

And heaven knows that in decades of the patient safety movement, piling on more and more data about harm has made no difference at all.

So the question I always ask is, “What can be said that will make any difference?”

In fact, I could ask: will “Break my heart, make me change” actually happen??

Very very difficult stuff.

Smoking cessation is a great example — you might remember the post I wrote about the QuitNet users panel at what was otherwise a pretty academic conference:

https://susannahfox.com/2010/10/11/building-a-research-agenda-for-participatory-medicine/

It was those stories of peer counseling that riveted the audience — the pixie dust that helped people quit and stay away from cigarettes.

How might we extend that idea to prevention of the spread of HIV?

My ideas: tap into our existing social networks, use our mobile phones, seed conversations with facts, energize our “local Lady Gagas” (to quote from another set of notes: https://susannahfox.com/2013/05/10/one-voice-many-inflections-hiv-clinical-trial-communications/ )

I’m very careful not to assume I know what another person’s life is like, so I hesitate to comment on what could change behavior at the moment of peak horniness. BUT STILL: the graphic makes me wonder (not know – wonder) – what is the difference, cultural or other, between what black kids do and others do?

And that makes me ask, hey, can we GET some black people in here? It feels creepy talking about [anyone] with them not here. Sorta like conferences wondering about patients without any in the room.

Very uncomfortable, this subject. Sorry.

I’m hoping that we don’t try to talk about any group, specifically or in abentia (as the case may be), but rather focus on our own observations and experiences, as Emily & Sarah & you & I have done so far.

While the graphic I posted at the top focuses on HIV rates among black Americans, I am aghast at the total picture in US and globally — all ethnic groups, age groups, etc.

I wrote this post to test my “someone like me” idea in an edgier context. I also wanted to share a bit what I’ve learned in my sexual-health conference travels (all the links at the end are to organizations and people I have met). In no way did I want to focus on “let’s talk about black people and why they are more likely to have HIV.”

I would love for us to focus on “How might we look at this data about HIV in the context of what we know about behavior change & tech adoption?” and more broadly, “How might we think differently about all conditions in this context?”

A relevant review article from 2013 that hits right at many of the points made:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3636069/

“Most available HIV/STD apps have failed to attract user attention and positive reviews.”

“detailed sociodemographic information (eg, user age, education, socioeconomic class, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and native language) should critically inform the tailoring and targeting of HIV/STD prevention and care apps.”

It sounds like they’ve been generally developed FOR the target users, not WITH. HMW fix that?

I challenge you to listen to an episode of “On Being,” the American Public Media spirit program. The guest was Seane Corn, National Yoga Ambassador for YouthAIDS and cofounder of “Off the Mat, Into the World.”

Listening to the 51 minute audio may be rough if you’re into this thread. She works in the fiercest of cruel situations – child prostitution from LA to Cambodia, facing their pimps, bringing the yoga way to the worst street reality.

How do you bring “all is well” to this reality? But what happens if you resist, starting from “This should not be?” Difficult, I know. (I don’t do yoga though people are telling me I should.)

The word that comes up for her is “fierce.”

Thanks for the emotions, behind your heart there is a clear vision of health promotion. Perhaps we need fewer drugs and more action against the social determinants of health

Giuseppe, thank you.

I do think the social determinants of health are the not-so-hidden, sneaking-all-around-us villains. But I wouldn’t say fewer drugs — I’d say we need broader access to the drugs that work AND to the mechanisms to contribute to drug development.

The article that Emily shared is a heart-breaking example of a socially-determined lack of access to a drug that works, in this case Kalydeco. The first 3 paragraphs tell the story:

“Vertex Pharmaceutical Inc’s $300,000-a-year cystic-fibrosis drug has sparked a legal battle here, where the state’s Medicaid program is restricting access to the expensive therapy.

In a lawsuit filed in Arkansas federal court last month, three people suffering from the fatal lung disease allege Medicaid officials have for two years denied them access to Kalydeco because of its cost. The plaintiffs allege state officials have violated their civil rights under federal law governing Medicaid, the government-run insurance plan for the poor.

The patients all meet the eligibility criteria established by the Food and Drug Administration when it approved Kalydeco in 2012, including the presence of a rare genetic mutation it is designed to correct. But Arkansas officials have said the patients must prove their disease has failed to benefit from older, less-expensive therapies, a policy their doctors say contradicts treatment guidelines.”

And then on Sunday, another heartbreaking article appeared, this time in the New York Times, also about access to drugs being determined by someone’s social (income) status.

$1,000 Hepatitis Pill Shows Why Fixing Health Costs Is So Hard

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/03/upshot/is-a-1000-pill-really-too-much.html

Excerpts:

“A new drug for the liver disease hepatitis C is scaring people. Not because the drug is dangerous — it’s generally heralded as a genuine medical breakthrough — but because it costs $1,000 a pill and about $84,000 for a typical person’s total treatment…”

And:

“But maybe we are looking at the costs of Sovaldi in the wrong way. One reason it is causing such angst among insurers and state Medicaid officials is that treatment costs are coming all at once.

First of all, there is pent-up demand. There are a lot of people with hepatitis C — an estimated 3.2 million in the United States — many of whom have been waiting for a good treatment. Second, unlike drugs for most chronic diseases, like diabetes or H.I.V./AIDS, for which treatment continues over many years, Sovaldi can cure most patients’ hepatitis in just a few weeks, with the bill soon to follow. The lifetime cost of treating someone with an H.I.V. infection is around $380,000, according to estimates from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but the annual bill is much smaller.

Think about AIDS treatment as paying a mortgage. Sovaldi is like buying a house with cash.” [emphasis added]

Click through to the comments on the article for an intriguing discussion (I’m just starting to read the comments myself).

How might we re-imagine health care payment structures to account for the possibility that a disease can be CURED, not just maintained?

I often think about how a “just in time someone like me” can help you navigate to a diagnosis, to a clinician who can help, to a treatment that your clinician may not have heard about yet, to a home care regimen that helps you heal, and so on. But I haven’t thought through how “someone like” can help in these situations — there is a known cure for you, and you know about it, but can’t get it. If anyone has thoughts to share on that question, please comment.

I can’t reply to Sarah’s latest comment, so I’ll start a new thread. She ends with this line:

“It sounds like they’ve been generally developed FOR the target users, not WITH. How might we fix that?”

How about we start by doing research and innovating toward solutions WITH target populations?

Today, the Washington Post ran the next installment of Jeff Guo’s reporting on the black HIV epidemic. It’s a must-read:

A public health mystery—and love story—from Atlanta’s gay community

http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/storyline/wp/2014/08/04/the-black-hiv-epidemic-a-public-health-mystery-and-love-story-from-atlantas-gay-community/

Notable excerpt:

“Inside the CDC, an order came from high up: Find out what was going on with black gay men. At the time, Millett recalls, there were few black scientists in the department, and certainly nobody who was black and gay and out. Millett was assigned to untangle the different theories about why this community—his community—was getting hit hardest by HIV.”

So the CDC recognizes the imperative to not do things FOR a group, but WITH a group. That’s good news.

As Dave points out, the topics of race and sexuality are uncomfortable. And I want to address the obvious point that I’m not OF the community being highlighted in Jeff Guo’s reporting.

I used the graphic at the top of the post as a jumping off point, but I didn’t address the specific issue of race in my post.

Instead I wrote about how visualizing health data is not enough. Being given information is not enough. Nothing, it seems, that we’ve come up with yet is enough because the epidemic marches on.

And I wrote about how I see a glimmer of hope in the fact that we all love our phones and we all love our own friends and families. Even if we don’t love ourselves, we might be able to reach down inside to preserve ourselves if the right trigger can be found, the right word at just the right time.

I am hoping that this “just in time someone like me” idea I want to promote can have an effect on people’s choices. That’s what I hoped the post would inspire — a broad discussion of the possibilities and limitations of that idea.

I’m not qualified to lead a discussion of race & sexuality. I leave that to the experts I link to at the end of the post and others — including visitors to this blog who want to share their expertise and experiences in the comments.

I am qualified to lead a discussion of tech adoption and use for health.

So again, I’d love to talk about Sarah’s question:

How might we work WITH target populations — of all types — to get closer to solutions that work?

And:

How might we incorporate the idea of a “just in time someone like me” in the flow of people’s lives, to guide them to better decisions?

Ran across this promising example this weekend–a fellow PCORI awardee project! Note the team includes patients.

http://pfaawards.pcori.org/research-results/2013/addressing-hiv-treatment-disparities-using-self-management-program-and

“Our team, which includes HIV patients, doctors, and HIV organizations, developed a training program to use a personal health record (PHR) for people living with HIV. Together with peer trainers, we will teach patients how to use their iPod and an interactive PHR, and how to ask their doctors questions that are meaningful to them. We will evaluate the effect of the training program by comparing patients who receive the program to those who don’t.”