Here are the remarks I prepared for the Feb. 6, 2014, Engage & Empower Me class at Stanford Medical School. It’s a long post, so if you’d prefer to zone out, you can watch the video.

In thinking about this class, I thought a good framing question for tonight is: How does change happen?

- How do political systems change?

- How do cultural practices change?

- How do business practices change?

And, more powerfully: How do you recognize when change is happening so you can surf the wave? Or even guide it and be part of team leading the change?

It’s my observation, backed up by some reading I’ve done, that systems change in 4 stages:

- The failure of an existing model

- The emergence of a successful model

- The participation of people affected by the system

- The adoption of a new model by powerful entities (sometimes after a revolution)

Recognizing change is what motivates me to be a student of participation – participatory research, participatory medicine, participatory democracy.

Most of what I’ll talk about today are cultural and business practices, which I think is apt since the practice of health care has its own culture and it is, like it or not, a business. My expertise is public opinion research and online behavior related to health, but I’ve collected a couple of examples from related fields that I think will be useful to you.

I want you to be able to recognize when change is happening. And I want you to seize the opportunity to be part of change when it comes to your field.

Failed models

Throw your mind back to the 1990s, when internet access was limited to universities and alpha geeks, when people still mostly looked stuff up in books printed on paper and information was not yet free to move about the country.

In those olden days, anthropologist Diana Forsythe conducted fieldwork in an artificial intelligence lab that was tasked with creating an information kiosk for newly diagnosed migraine patients. A big box with a screen that would sit in the waiting room of a doctor’s office.

The idea was that patients could walk up to the kiosk, punch in questions, and get some answers before or after they saw their doctor. It was a nice idea, ahead of its time in some ways. But when it launched, it was a failure. Patients didn’t use it after their first try. Why? Because the kiosk’s designers had not asked patients what they wanted to learn about migraines. They relied on an interview of a single doctor to tell them what he thought patients should want to know.

Can’t you just see the designers, holding their clipboards, the shield of many a know-it-all, interviewing that one doctor?

As Forsythe wrote:

“The research team simply assumed that what patients wanted to know about migraine was what neurologists want to explain.”

The mismatch was complete. The kiosk failed to answer the number one question among people newly diagnosed with migraine: Am I going to die from this pain? It’s an irrelevant, even silly question from the viewpoint of a neurologist, but it is a secret fear that people may have felt comfortable expressing to a kiosk, just as now we ask that blank search box on Google our secret questions.

Contrast that with the approach taken by one of the premier product design organizations in the world: Procter & Gamble.

I was lucky enough to be in the room a few years ago when their head of global research briefed White House officials on how to improve their communications around HIV. In order to improve, he said, you should adopt the P&G mantra: “Listen, more than ask.” Instead of conducting surveys and focus groups, thinking that they could anticipate the right questions to ask, P&G now listens in on social media, adapting their communications and product designs accordingly.

If P&G can put down the clipboard and put on their listening ears, why can’t we?

Let me tell you another story about the failure of an existing model: telephone survey research. The ultimate “I have the clipboard” methodology in which people are interrupted during dinner and kept on the line for 20 minutes answering yes, no, agree, disagree.

For 50 years, the research industry has relied on telephone surveys to get an accurate snapshot of people’s attitudes, opinions, and behaviors.

The Pew Research Center, where I work, is one of the gold standard organizations in the field. My colleagues in the political research division pride themselves on being able to call the outcome of the presidential election with incredible accuracy, pulling it off like a magic trick every four years. People count on us to do the counting.

But check it out: We have gone from a response rate of 36% of households in 1997 in the U.S. to just 9% in 2012. We are losing the signal.

More and more people are mobile-only instead of having a landline, which raises the costs of conducting a survey and complicates our calculations. Fewer and fewer people are willing to answer the phone when we call, much less answer our questions. The ones who do take surveys are demographically and politically different from those who don’t – and that, my friends, is a fatal flaw.

But we noticed something intriguing this past year. The Pew Research Center started putting short versions of our questionnaires online for people to answer, like a quiz, and see how their answers stack up against our national results. Those quizzes have been completed millions of times.

What’s the difference? The online quizzes give the respondent immediate, personalized feedback. They learn something about themselves, even as we learn about them. Put another way: We let them participate. We let them look at the clipboard.

Emerging models

I’ve talked about two failed or failing models and two emerging models. Let me put some meat on the bones of the emerging models and relate it to health care.

That migraine kiosk story was shared with me by my mentor, Tom Ferguson, an MD who believed in the power of listening to patients and giving people access to information.

I had studied anthropology and how to be a “participant observer,” so I understood why it is important to listen and observe in a thoughtful and respectful way but Tom helped me put it into practice as a researcher, back in 2002. We fielded a 20-question online survey and invited people from 3 online patient and caregiver communities to participate. 1,971 people wrote short answers and essays in response to our questions.

Frankly, it was incredibly labor-intensive work compared with analyzing telephone survey results. I spent hours reading people’s answers and I did follow-up interviews with 19 people.

By contrast, telephone survey results are so clean, orderly, anonymous, and relatively easy to interpret. Or, as Sir Austin Bradford Hill said: “Health statistics represent people with the tears wiped off.” Before I met Tom, that’s what spent my working days doing: looking at statistics, adding columns to 100 and telling clean, orderly stories.

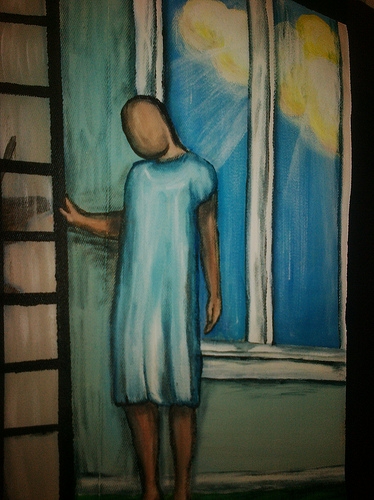

This is my Walking Gallery jacket, painted by Regina Holliday. And that sad, faceless person represents anonymized data. A person with the tears wiped off. Regina painted the data mote standing in the sunlight because statistics do shed light – and notice the cloud in the sky, because data often lives in the cloud. But she also painted the person looking a little downcast, with their hand on the screen, maybe wanting to reach out to me, where I’m hiding a little bit, not telling people what I really think, not showing my humanity.

This is my Walking Gallery jacket, painted by Regina Holliday. And that sad, faceless person represents anonymized data. A person with the tears wiped off. Regina painted the data mote standing in the sunlight because statistics do shed light – and notice the cloud in the sky, because data often lives in the cloud. But she also painted the person looking a little downcast, with their hand on the screen, maybe wanting to reach out to me, where I’m hiding a little bit, not telling people what I really think, not showing my humanity.

Well, there was no turning back after I completed that first fieldwork project. I realized that there was zero chance of me being a successful researcher in this emerging field if I didn’t listen to people’s stories about how they were using the internet to gather, share, and create health information. I had to give up the clipboard sometimes and let people just tell me what they wanted to share, in their own words. I had to put the respondents at the center of the research process. I had to listen, more than ask.

And now it’s me wiping the tears off my own face. I learned that I have to do much of my fieldwork analysis at home, not at the office, so I can cry. Anyone who works in health care will tell you the same thing, I think. You’re going to cry. But there is no other way to go if you want to get at the truth. And that’s my mission as a researcher. To tell the truth.

I use fieldwork to look for patterns among the patients and caregivers I follow and am friends with, asking for their help when I am choosing new topics to research. By being a participant-observer in the world of health care social media, I stay ahead of the field and anticipate where to focus the spotlight of research. I can give examples during the Q&A if you’d like.

Participation of the people affected by the system

Now on to the third part of successful change: participation by the people affected by the system.

I need to pause here to quote Pete Seeger, the folk singer and activist, who passed away recently. He said, in one of his last public appearances:

“I’ve never sung anywhere without giving the people listening to me a chance to join in…I guess it’s kind of a religion with me. Participation. That’s what’s going to save the human race.”

I love that quote. It reminds me, again, of Tom Ferguson, who was one of the first doctors in the U.S. to recognize the internet’s potential for health care, writing about it as far back as 1987.

He coined the word “e-patients” to describe people who are “empowered, engaged, equipped, and enabled.” The fact that the “e” could also stand for “electronic,” meaning online, was also part of Tom’s thinking. When he was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a rare form of cancer, Tom put those principles to work on his own behalf, networking with both patients and clinicians to track down the latest therapies and the best treatment centers.

He lived in Austin, TX, but his investigations brought him to Little Rock for treatment at the Myeloma Institute for Research and Therapy (MIRT) at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Even as he went through chemotherapy, Tom worked with his clinicians to improve the patient experience at MIRT. They set up a system to collect confidential feedback from patients and made immediate improvements to two hot spots: wait times in the clinic and at the pharmacy.

Naturally, staffers were not happy when they received specific complaints about their work and morale sagged. But Tom was a thoughtful and generous spirit. He not only noticed, but came up with the idea for and personally funded a rewards program for staffers who received a positive report from a patient. Staff morale improved and they more eagerly embraced the new model of listening to patient feedback.

Adoption by powerful entities

Unfortunately, Tom died in 2006 from complications related to his cancer treatment. But Dr. Elias Anaissie, his oncologist, carried on with the initiative, eventually helping to create a participatory care model that has been embraced by patients, caregivers, and clinicians. Tom’s humility infuses the approach, which places patients at the center, asking them how they would like to receive treatment instead of allowing clinicians to choose based on their own preferences or assumptions.

MIRT has recorded improved clinical outcomes since the system’s implementation, but just as important are the improvements to the quality of life enjoyed by their patients being treated for multiple myeloma.

The following story is included in a journal article about the new care model:

A 40-year old male from Illinois was diagnosed with multiple myeloma in May 2005 and referred himself to MIRT in August 2008 because his disease was no longer responding to the treatment he was receiving in his hometown and had metastasized to the liver, a very ominous sign usually associated with very short survival.

He moved to Little Rock with his wife and their 4-year-old son to undergo multiple myeloma treatment with the expressed desire to be treated as an outpatient because he wanted to spend as much quality time with his young son as possible. The patient responded well to therapy for more than two years during which he actively participated in raising his son, playing their favorite game of baseball [together].

By early 2011, the patient’s multiple myeloma became less responsive to therapy and he [died] on the inpatient service in late April 2011. Two days before his death, the patient expressed his desire to watch his son’s baseball game because the boy had told him, “Dad, I want to hit a good one for you.” The medical team made special provisions to honor his request so he could experience his son’s excitement when he did indeed score one for him.

Tom Ferguson’s legacy is that everyone recognized the importance of that man’s wishes and shifted their plans in order to accommodate them.

Tom saw clinical care as one piece of life’s puzzle. A person’s own motivations and values form other pieces. Tom recognized that clinicians shouldn’t try to fit the puzzle together for their patients, but rather act as a guide when life intersects with medicine.

Tom knew that clinicians would never have all the answers. Instead he showed them how to honor people’s questions and encouraged patients and caregivers to keep asking them. In this way, Tom taught us all how to be a little more human and we are the better for it.

Back in 2002, when Tom and I were working on that first project together, he said we should have a text box next to every single question, even the ones that just asked for basic information. He wanted people to feel like they could push back on any question or explain more, rather than just be limited to yes, no, agree, disagree. He also advised me to make the last question as open-ended as possible: Is there anything else you’d like to share? And guess what? That single question yielded more insights than the other questions I wrote, clutching my clipboard.

So, here’s what I’d like to leave you with: My advice.

- Put down the clipboard. Bring your whole self to your work. Don’t be afraid to be human.

- When you have the opportunity, ask: Is there anything else you’d like to share?

- Stand on the shoulders of giants. Learn the techniques of people who have studied and perfected participatory research.

Explore the resources I’ve collected and join me on the path.

My Pew Research Center colleague Michael Suh pulled together the 2013 totals for our quizzes:

Online Dating: What’s Your View?: 9,637

The News IQ Quiz: 1,268,328

Science and Technology Knowledge Quiz: 4.485,867

How Millennial Are You?: 588,585

U.S. Religious Knowledge Quiz: 465,047

Global Christianity Quiz: 5,253

Yes, that’s right: 4.4 MILLION people took the science quiz.

Try your hand at a few:

Pew Research Center: Quizzes

I’m so glad that you posted this here and so sorry I had to miss your MedX Live event.

My question is a bit of a tangent from your main point, but it’s sticking out to me. This part about crying was very poignant:

“I learned that I have to do much of my fieldwork analysis at home, not at the office, so I can cry. Anyone who works in health care will tell you the same thing, I think. You’re going to cry. But there is no other way to go if you want to get at the truth. And that’s my mission as a researcher. To tell the truth.”

My comment/question is to wonder out loud why we can accept that crying is part of this line of work, and listening to patient stories, but that it still must be done in private. It’s that sort of contrast where we are evolved enough to be okay talking about it, but not to the point of being comfortable crying out in the open. I wonder if the preference for working from home is because it makes you more comfortable, or it makes your coworkers less uncomfortable. And is there something we could do to get this more accepted and embraced in medicine, and beyond.

SUCH a good question. And don’t worry, I don’t see it as a criticism at all (re: your second comment).

I think the truth is a mix — my own comfort level with appearing in the lunchroom with red eyes and taking more than my fair share of tissue boxes out of the store room AND what really is my perception of my colleagues’ feelings of being uncomfortable with my tears (rather than any comments they have made to me beyond kind concern).

I’m a little bit of a unicorn at the Pew Research Center with my interest in both fieldwork and health research — not so many tears down the hall where my colleagues who track politics and the media sit! Well, except for those who are tracking the news business (only kind of joking).

Your question gets to a deeper point about the broader context of health care communications, including conferences. I love it when a speaker — whether a clinician, patient, caregiver, policymaker, etc — tells a heartfelt story to make a point. Other people have said that a tearful presentation can seem contrived and distracting. I personally have never felt that way, but I could see how it would make some listeners uncomfortable. And there is certainly a line that can be crossed.

Then again, I just read this opinion piece written by a nurse about how clinicians should be more human in their communications:

Lost in clinical translation

I want to be clear that comment is in no way meant as a criticism.

I’m glad you put up your prepared remarks in addition to the video. It’s different reading something … with the opportunity to pause and think … than watching the video. It’s funny though. It’s not an issue of clipboards vs observation, as if one is superior to the other. Rather these are different tools for learning, and one must appreciate the advantages and disadvantages of different tools and use the best tool available. Deep observation is critical for disruptive innovation. But rigorous and detailed data collection (like with clipboard surveys) is critical for continuous improvement.

It’s interesting that you mentioned Procter & Gamble, as P&G were the pioneers in focus groups and such. But they have continued to innovate in market research and have re-discovered the value of ethnographic research. Here’s a passage from “The Game-Changer” written by P&G’s CEO A. Lafley:

“Our research has moved away from traditional focus group research and invested heavily, to the tune of a billion dollars (double the industry average), in consumer and shopping research, with particular focus on IMMERSIVE research. We’re spending far more time in context with consumers — living with them in their homes, shopping with them in stores, and being part of their LIVES.” [In the original, “immersive” and “lives” are italicized.]

Another passage from “The Game-Changer” that really resonates with your point:

“In the end, customers cannot always tell you what they truly want. It is up to you to listen, to observe, to make connections, and to identify the insights that lead to innovation opportunities. … it all starts by doing something simple — keenly watching customers, face-to-face, knee-to-knee, and listening, with ears, eyes, heart, brain, and your intuitive sixth sense.”

Thank you! I’m so glad you’re putting in a word for quantitative data collection — truly, it is just as important as the qualitative work. I take that for granted since I mostly interact with colleagues who are 100% focused on quant methods. I have found that our most successful projects are able to balance the two, almost in a cycle of listening, asking, listening, asking.