The Cajun Navy – people who rally their personal boats to rescue hurricane survivors – is an example of how ordinary citizens are the true first responders in a disaster zone. Instead of seeing locals as liabilities, the Federal Emergency Management Agency has started looking for ways to support their work.

As David Graham wrote in The Atlantic:

“When you step back and look at most disasters, you talk about first responders—lights and sirens—that’s bullshit,” Craig Fugate, who headed FEMA during the Obama presidency, told me in 2015. “The first responders are the neighbors, bystanders, the people that are willing to act.”

That underpinned “whole-community response,” the principle around which Fugate organized FEMA during his eight years in office…The basis for whole-community response is that, while the government simply can never provide a response as quickly as needed, a top-down response from the government isn’t the best answer anyway. Local people know much better what they need, and they benefit from being involved.

I think we need to create a “whole-community response” in health and health care. We need to acknowledge that our “locals” (aka patients, caregivers, and other non-professionals) are essential partners in a health crisis.

Now, where to start? Personally, the ripest target I see is the resurgence of vaccine-preventable diseases, such as measles. Misinformation about vaccine safety is the number one issue that people bring up when I talk about peer-to-peer health advice – and for good reason. Anti-vax voices are very loud on social platforms and they have been wickedly effective at grabbing the attention of people who are hesitant about immunizing their children. For a long time, I didn’t have an answer for critics who said we should discourage ALL peer health advice because of this very real, very awful negative consequence of people finding these sources of misinformation online. I needed a way to stretch out the tangle of anecdotes and stories, to show people a different view of the situation.

I’ve been working on a model to try to explain what I see as an opportunity to call out our own version of the Cajun Navy:

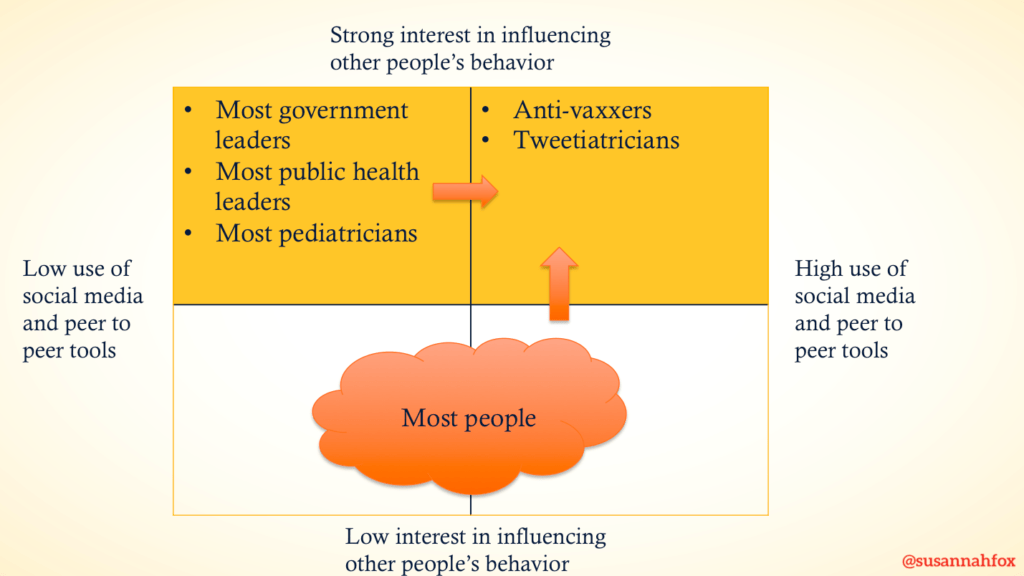

The vertical axis represents strength of interest in influencing other people’s behavior related to vaccine (strong at the top, low at the bottom).

The horizontal axis represents use of social media and peer-to-peer tools. At the left side are those who have zero or low engagement with those tools. At the right are people who use those tools often.

I should note that I was limited by space when I created this slide. If I could, I’d add the concept of ineffective vs. effective use of social media and peer tools to the horizontal axis.

Organizations and people I would put in the top left quadrant include most government leaders, most public health leaders, and most pediatricians.

Organizations and people I would put in the top right quadrant include anti-vaxxers and “Tweetiatricians” (pediatricians who use Twitter and other social tools well, like Wendy Sue Swanson, MD).

Anti-vaxxers are skilled at using peer to peer networks, online and offline, while the government and most pediatricians and advocates are not. The first step to solving this, though, is recognizing that we on the side of science and disease prevention have a problem. We need to engage in peer networks and help boost the signal for science among those who already have clout in their peer health advice networks.

How might we move more people from the left side to the right? How might we upgrade people’s skills and engagement?

The whole bottom half of the chart is filled with what I would characterize as most Americans. Most people (93% according to the U.S. Surgeon General) vaccinate their children on time. But we need 95% for herd immunity. And the vaccination rate in some communities is much lower. How might we motivate people to take part in peer-to-peer conversations about vaccines — how safe and effective they are, how awful the diseases are if we don’t keep them at bay.

How might we pull more people from the bottom half of the graph to the top right? That is, how might we pull more potential allies off the bench and onto the field? Some people in the bottom right quadrant are highly skilled at social media and would be fabulous allies. Others may not yet be active in this area of life, but could be motivated to engage if they see a threat to their own families.

For example, we can learn from people like Kim Nelson, a field marshal in the fight against misinformation. As Alex Olgin of NPR reported:

“Nelson started her own group, South Carolina Parents for Vaccines. She began posting scientific articles online. She started responding to private messages from concerned parents with specific questions. She also found that positive reinforcement was important and would roam around the mom groups, sprinkling affirmations when people get their kids’ shots done.

“Nelson was inspired by peer-focused groups around the country doing similar work. Groups with national reach like Voices for Vaccines and regional groups like Vax Northwest in Washington state take a similar approach, encouraging parents to get educated and share facts about vaccines with other parents.”

Let’s ask her what she needs and then support her, again in the same way that FEMA supports the first responders who live in communities affected by a disaster.

Now, here’s where I need your help. What is missing from this model? What dimensions and examples would you add to it? Or do you fundamentally disagree with it?

When I shared it with participants in the Digital Health Promotion Executive Leadership Summit on June 3, 2019, they suggested:

- Add educators to the list of people who want kids to be vaccinated and stay healthy. Teachers and school administrators have an opportunity to reach parents directly.

- How might we improve health literacy more broadly, so that when people do engage on social media they are sharing valid information?

- Add a dimension that accounts for offline relationships, particularly for geographically-bound networks of people (such as Orthodox Jews in New York, who are experiencing a measles outbreak).

- Add a dimension that relates to micro-targeting of audiences.

- In May, Twitter launched a tool to combat misinformation, linking to credible sources when people search for vaccine-related key words, so we should add social media companies to the chart, depending on their engagement with the issue.

- People on the left tend to “shout” on social media whereas people on the right are more likely to engage in a conversation. How might we help public officials understand that they can’t stick to a broadcast, one-to-many model of communication?

- Motivation is key. How might we help people who are not currently concerned about their neighbors or kids’ classmates immunization rates see that they should be paying attention? For example, herd immunity is important for the protection of vulnerable people in a community like newborns and people going through cancer treatments.

- Echo chambers are a danger at all levels of the conversation. Academics, for example, are likely to follow each other instead of engaging with the public more broadly. Anti-vaxxers have been very good about engaging with a wider population.

- The current model makes the anti-vaxxers and Tweetiatricians look equal in size and influence to all the groups on the left (most government leaders, most public health leaders, most pediatricians) when they are not equal. The suggestion was to add a dimension of size and impact to the illustration.

- For young people, memes and viral content have the potential to bring attention to issues. Sometimes it’s funny AND accurate (and sometimes it’s not). How might we find ways to leverage memes for health education?

- Is it true that if we “flood the zone” with valid information, if we are able to move more people into the upper right quadrant, more people will vaccinate their children? That’s an open question given what we know about source credibility and fitting information into what people already think about an issue. There was a suggestion that this is a model for “information countermeasures” but we need more than that, such as “education countermeasures” such as helping people to spot misinformation.

- Trust is key. We need to focus on what motivates people, find out who they trust, and feed good information to those sources.

- This is a model for vaccination but be careful: It would look very different for smoking cessation and other public health issues.

On Twitter, @Init4Health shared a link to an article about Susan Nasif, MD, a “virologist-turned-cartoonist” who creates comics that educate kids about flu, polio, Zika, and other diseases.

What else are you seeing in the field? Please share ideas and observations in the comments.

Featured image: Measles, by Dave Haygarth on Flickr.

I think your model works well. One group that needs to be on the chart is school nurses. I think they are as important or more so than admins. A few years back NJ offered a workshop (CME credits) to educate school nurses and public health nurses about HPV vaccination and ways to communicate the information. Provide those nurses with anbrochure and links to reliable information to disseminate to parents

cine too.

Thanks, Dee! Great addition.

Here’s an update from this morning’s headlines:

How Measles Detectives Work To Contain An Outbreak: Across the nation, public health departments are redirecting scarce resources to try to control the spread of measles. Their success relies on shoe-leather detective work that is one of the great untold costs of the measles resurgence.

A quote:

“During a 2017 outbreak, Children’s Minnesota, a hospital system in the Twin Cities, spent $300,000 on their emergency response. Part of that was tracking down everyone in the waiting room within two hours of a measles patient.”

Maybe if people realize how much money we lose when people are not vaccinated, more will be called to not only get their own shots up to date but amplify it as fiscal responsibility as well as personal health responsibility.

YES.

Very thankful to our Cajun Navy who have rolled up their sleeves to help with peer support group governance and privacy resources. We’ve gotten incredible responses from support groups who are trapped like my own. How do we help them? https://tincture.io/our-cancer-support-group-on-facebook-is-trapped-f2030a3c7c71

There are digital health disaster areas on social media right now. Right now we only have the Cajun Navy working around the clock. There absolutely needs to be a FEMA level relief effort – and yet the only way for it to be effective is from the bottom up + grassroots.

Fantastic piece!! More please ( :

Thanks, Andrea! Stay tuned — I’ve found this framework to be useful in looking for untapped energy sources in health & health care and will be blogging more about what I’m seeing.

To all who are reading along: Please take some time to digest and then come back to share your ideas, critiques, links to supporting evidence, etc.

Rachel Martens wrote on Twitter:

“One thing I’ve been encouraging are some of the dynamics of #scicomm with fellow parents citing ‘few have life altering view changes from being called stupid on FB’. Not a lot of people understand what it means to have healthy discourse online.”

And: “This video tackles a lot rather globally. When one adds the layer of health and associated stresses, there is an added complexity. We have this added energy/agression that needs to be filed somewhere. Makes misinformation an easy target for that energy. I should add by aggression/energy it’s a need to explain or reconcile how our lives have been impacted. This is why I support online communities even still. If we could build ideas in engagement in these groups, we could have the potential to be a informational compass.”

Maneesh Juneja shared this comment on Twitter:

“I have recently come across some research which has made me think again about how we combat health misinformation using social media. It’s not as simple as we thought.”

He linked to: Weaponized Health Communication: Twitter Bots and Russian Trolls Amplify the Vaccine Debate

If more Americans knew what we are dealing with, would they come off the bench and join public health leaders in promoting science and truth?

One of the questions raised at the June 3 event focused on whether peer-to-peer information exchange actually has any effect on people’s behavior related to vaccine. I remembered a blog post that Wendy Sue Swanson, MD, published in 2017: Online Interventions Improve Vaccination Rates

Because it’s so salient, I’m going to paste a long quote from it here:

QUOTE:

US Study Finds Blogs And Social Media Influence Infant Vaccine Status:

Pregnant moms exposed to online blog content about immunizations and social messaging about the science and safety of vaccinations were more likely to vaccinate their infants on-time during infancy than moms who received regular routine care without exposure to online education. Basically, moms who were given blogs and social media messages with education and explanations about immunizations were better about ensuring that their infants got their vaccines on-time. Hooray! Here’s how the researchers came to this conclusion:

A randomized controlled trial was done in Colorado from 2013-2016 and included 1093 pregnant moms. Moms were evaluated for vaccine-hesitancy (about 14% of moms were hesitant). The population was fairly affluent (>50% have family income >$80,000/yr) and very educated (>80% of moms had college education or more) and internet savvy (>60% said they used the internet every week or health info).

These pregnant moms were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups who would receive:

A website with vaccine information and social media components

Just the website with vaccine information

Usual care with neither a website nor social media information

Researchers followed up on the infants’ shots 200 days after birth. They also evaluated for the Measles Mumps Rubella (MMR) shot given around a year of age. The proportion of infants up-to-date on their vaccines for the first 200 days:

92.5%– babies with mom’s who received website + social information

91.3% – babies with mom’s who received just the website

86.6% – babies with mom’s who received usual care

A victory! In addition, the babies got their MMR vaccinations at impressive rates, too (95%, 95%, and 92% in respective groups). Although I’d say all groups of these moms and babies did a good job keeping their infants up-to-date, moms with more access to education, starting while still pregnant, did the best.

So go forth and keep spreading the positive word about vaccines, their safety, their science and their ability to keep our population healthy!

UNQUOTE

The Seattle Mama Doc blog is a treasure trove of evidence, written in an engaging style so that you WANT to keep reading and learning. Here’s another great post from 2015: Vaccines, Profanity, and Professionalism. It links to a study published in the journal Pediatrics that is also worth a click: Physician Response to Parental Requests to Spread Out the Recommended Vaccine Schedule. Here’s the conclusion:

“Virtually all providers encounter requests to spread out vaccines in a typical month and, despite concerns, most are agreeing to do so. Providers are using many strategies in response but think few are effective. Evidence-based interventions to increase timely immunization are needed to guide primary care and public health practice.”

How might we not only support pediatricians who need better talking points but ALSO reduce the number of parents who are asking to delay vaccination? There are peer to peer outreach opportunities for both groups.

Great article Susannah relating to a growing problem of those who are being influenced by non-scientific discussion based on “this is what I think” vs what is known. In that context, the issue is even bigger because the “fight” shifts to the world of alternative facts and people taking opinion as fact. And it’s not just an issue of education. I know some very well educated people who operate in this manner, trained in the scientific method, they take the position of their preferred opinion is their “fact”, regardless of being contrary to 100% proven fact. It’s rather frightening and not sure a social media/celebrity spokesman war is really the answer.

Thanks, Howard! I agree that a celebrity war is not the answer (and I’m disappointed by the media promoting — and bungling — the latest example.)

If you see more examples of people speaking up in their communities (online, offline, wherever) please let me know.

Meantime, I started thinking about my own responsibility as a parent raising kids who I hope believe in the validity of science and the importance of herd immunity. One way I’ve found to introduce my kids to concepts like the importance of vaccines, public health, international coordination of emergency response to disease: Pandemic, the board game. It is our favorite game, by far. How to play: https://youtu.be/4RxqzBA_HRs

Great new JAMA article to read for further inspiration and tactical planning:

Employ Cybersecurity Techniques Against the Threat of Medical Misinformation, by Eric Perakslis, PhD1, and Robert M. Califf, MD

Love how they also advise “adopting the toolsets used by their potential adversaries,” such as white hat hackers and other security watchdogs who can safeguard informational websites.