The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) will kick off their annual meeting on Tuesday, October 31. I will moderate the first panel, “Access to Results That Matter,” and, as I like to do, I’m starting the conversation early online.

Here’s the session description:

Traditional health research often does not provide the answers to patients’ questions about the health challenges they face. And even when such evidence is available, it often isn’t easily accessible when and in the forms that patients need. One reason for this is that patients, their families, and many other healthcare stakeholders, along with the questions most important to them, haven’t necessarily been part of the traditional research process. That’s changing, with PCORI among the reasons why. This session will explore how we can do a better job of producing more relevant evidence for patients and other healthcare stakeholders and how we can get it to them in more useful ways.

After a keynote by Freddie White-Johnson, MPPA, the following group will discuss the issues:

- Stephanie Buxhoeveden, MSN

- Bishop Simon Gordon

- David Lansky, PhD

- Sharon Terry, MA

- Diane Padden, PhD

Here’s my request: What questions do YOU have about clinical research and how results are shared? Please post in the comments below and I’ll try to ask them at the event on Tuesday.

If you’d like to play along at home, here are the 3 questions I asked the panelists to send to me in advance:

- What is the question on this topic that you would LOVE to be asked?

- What is the question that you DREAD? (Note: could be because it’s a tired cliche; annoying; too close to a nerve; impossible to answer…)

- Where do you see possible areas of DISAGREEMENT in the research, clinical, and patient/caregiver communities?

For example, I’m a fan of the critique that Ben Goldacre articulated in his TED talk (below) but I know that it would be a potential area of disagreement among researchers who accept industry funding:

A quote:

“…unpicking the evidence behind dodgy claims isn’t a kind of nasty, carping activity; it’s socially useful. But it’s also an extremely valuable explanatory tool, because real science is about critically appraising the evidence for somebody else’s position.”

Another, explaining why industry-funded studies always show positive results:

“…the negative data goes missing in action; it’s withheld from doctors and patients. And this is the most important aspect of the whole story. It’s at the top of the pyramid of evidence. We need to have all of the data on a particular treatment to know whether or not it really is effective.”

And finally:

“I think that sunlight is the best disinfectant. All of these things are happening in plain sight, and they’re all protected by a force field of tediousness. And I think, with all of the problems in science, one of the best things that we can do is to lift up the lid, finger around at the mechanics and peer in.”

So much of research is protected by a force field of tediousness! How might we use the power of PCORI — and other funders and leaders — to break that down? How might we get the right evidence, at the right time, to the right people, in a way they can understand and make an informed choice? How might we be sure that negative results are shared as broadly as positive results?

Please share your questions, comments, and concerns below.

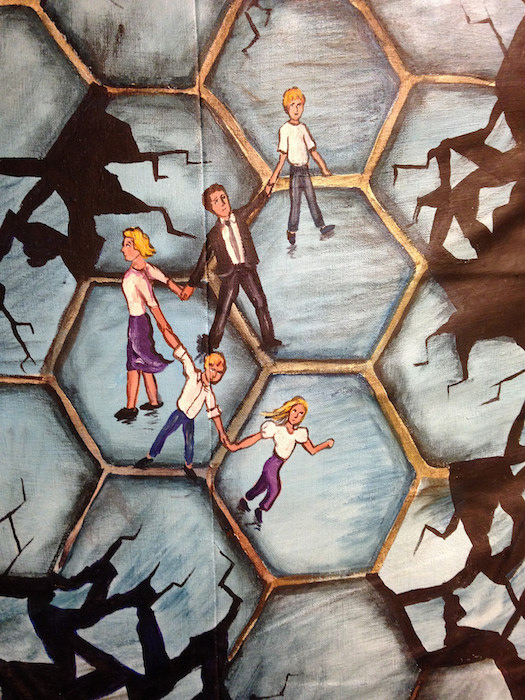

Featured image: Regina Holliday’s Walking Gallery painting for Todd Rowland, “Connected.”

Some questions:

(1) Most people don’t participate in clinical research. Why do you think this is the case? If you could fix one thing, what would you fix?

(2) There is a movement to have patients control their health data records.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2654934

Should this movement include data generated in a research study (i.e. uninterpreted data)?

Nice! Thanks, Jason.

If you have a chance, read this essay by Freddie White-Johnson, about her work in the Mississippi Delta and why people don’t participate in clinical trials:

https://www.pcori.org/blog/building-awareness-health-research-mississippi-delta

Here’s a quote:

“Part of health education is teaching about the concept of research. Awareness is the first step needed before actively engaging community members in research, whether as study partners or participants. In the Delta, people my age automatically associate the term research with the infamous, unethical Tuskegee experiment, and they fear participation. This is why it’s key to thoroughly explain the research process in a way people can understand. PCORI’s Engagement Award supported our efforts to do that with our training materials on research’s potential to positively impact lives in our community.

I find that once people in the Delta do understand the concept, those considering participating in a study are often most interested in knowing how it can benefit them. The expectation is that it will save their lives. In the Delta more generally, people tell us that they want to learn more about their risk factors and the symptoms of different diseases. PCORI has enabled us to hire people to go into areas we haven’t reached previously to spread knowledge about health and research. This has led to more people contacting us with an interest in cancer screenings. I’ve seen firsthand that what people learn about health risks has the power to change lives.”

Speaking personally, I’ve had family members who participated in clinical trials that were successful and others that not only didn’t yield any positive clinical results but were truly awful, including life-threatening complications, and the clinician dropped the patient like a hot potato. Personally I intend to ask any lead researcher/clinician recruiting me or a family member in the future: What happens when we wash out of your trial? Will you still care for our loved one? I am in favor of clinical trials, but I can see why some people hesitate.

In case people missed it, this NPR story yields more insights on trial hesitancy:

Troubling History In Medical Research Still Fresh For Black Americans

http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/10/25/556673640/scientists-work-to-overcome-legacy-of-tuskegee-study-henrietta-lacks

I am the patient Co-PI for a PCORI funded network and this is a question we are grappling with now. We have participants, we have longitudinal data, and we have promised to give back to everyone who has joined us. For now, everyone in our PPRN can see their data and the aggregate data of the entire cohort. With the help of some amazing biostatisticians, we are looking for patterns in data that are meaningful. As we uncover these it’s simple to relay number and results, but people are not just numbers. The patients in our PPRN need actionable items – things that they can use in medical encounters and on their own to improve their health, healthcare and QOL. What that looks like we’re not quite sure.

I will be at the annual meeting and look forward to your opening with this panel. As a note, Stephanie Buxhoeveden is a member of our PPRN, iConquerMS, governance committees and this is a very relevant topic for us. Thanks and see you in DC.

Thanks, Laura! Can’t wait to see you and be part of the conversation IRL. You bring up a key point: How might we deliver relevant results that help people take action or make a better decision? That is a high bar.

Question 1-

so everyone loves patients to be ””involved”” as clinical trial participants, donators of biopsies and data, indiscriminate fundraisers for clinical research and grateful disseminators of results. The moment patients however take issue with clinical trial motivation and design (inferior comparator, randomisation, blinding, placebos, irrelevant inclusion) this usually ends up with a below-the-belt ad hominem argument and gets criticised as the ‘unscientific bias of the un-educated’. How do get from the pseudo-patient-involvement-for-personal-convenience to a Science truly respectful of what patients need and want?

It’d be helpful to know who was excluded from the study (e.g. a smoking cessation drug excluding people with depression) and why. Often, even when something does work for people they become advocates for it – and they may not realize the limits of the research in terms of who we know it helps/doesn’t help, etc. Generally, it’s not explained or understood by patients and clinicians who the findings are relevant for. That’s right, i’m ending on a preposition 🙂

What is the question on this topic that you would LOVE to be asked?

I would LOVE to be asked how we can elicit more critical questions from people living with health issues. And, how can we answer those questions.

What is the question that you DREAD? (Note: could be because it’s a tired cliche; annoying; too close to a nerve; impossible to answer…)

Hmm – I don’t ever DREAD or even dread any question. So – hmmm – even sort of annoying… I guess if someone asked (but were really telling me with a tinge (or big dose) of paternalism): “Don’t you think researchers and/or clinicians know better than patients what should be researched and what should be reported back?”

Where do you see possible areas of DISAGREEMENT in the research, clinical, and patient/caregiver communities?

Ah – most of these stem from a clear disconnect in health and medicine of the needs of the customer (person living with a disease or condition) and the incentives and motivations of researchers and providers. They include: 1) people are not smart (literate, educated, aware) enough to know what they need or to decide what results they should receive; 2) misrepresentation of people’s preferences with regard to sharing and access; 3) misplaced concern about nefarious use of results. I think I can go on and on, but will stop there.

Clinical trial communication needs to start with the primary care physician. This is not practiced today. If it becomes part of this dialogue then we will see participation become more mainstream.

This communication needs to start with participants in trials. Biomedical research is the only industry that we expect to manage everything from the top down. Until we get over that, and start with individuals, we will not be successful.

I agree that negative results need to be shared to build a truly transparent view of the research.

Adverse events need to be clearly documented and explained – not just the percent who experience specific adverse events but some commentary on inclusion and exclusion criteria which may have consequences for those adverse events and a broader population.

How about the true cost of the drug/treatment being developed and what does that mean for the cost to the consumer?

We need more studies which provide home visits and telemonitoring for follow up instead of frequent office visits for research subjects which can be a time and financial burden. Could results in more participants also.

John, I was inspired by your comment to make my closing question: If I gave each of you a magic wand, what ONE thing would you change to improve the research pipeline? (I then kicked it off with your suggestion about home visits.)

David Lansky suggested we capture people’s self-reported functioning and health status using their mobile devices, feeding that data into the care system.

Stephanie Buxhoeveden would change the perspective that “patients are subjects” to “patients are participants” in research and there to actively collaborate.

Bishop Simon Gordon would include family in the dialogue, all along the research process.

Diane Padden would create one place that is easily accessible for everyone – patients, caregivers, clinicians – with the latest evidence, laid out in easy-to-understand infographics to spark discussions among the stakeholders.

Sharon Terry would free all the data and allow it all to be liquid, flowing, and “everywhere.”

I am on the steering committee of a PPRN as a patient stakeholder. I also am the prior patient editor of The BMJ, and now I work at a large corporate healthcare organization. I am in the audience today as a patient scholar. How do you suggest we bring ideas of patients included and patient-centered to slow corporate workplaces? And show ROI?

Thanks so much for making the jump from Twitter! I’m sorry I don’t understand the question: What do you mean by “slow corporate workplaces”? Do you mean we need to slow down their fast pace in the interest of being more friendly to patients and caregivers in some way? Or do you mean that corporate health care is slow in adopting patient-centered practices?

It’s just not true that all industry sponsored research shows positive results. For example: http://www.fiercebiotech.com/biotech/alzheimer-s-hopes-dashed-as-lilly-gives-up-amyloid-drug-solanezumab

Having said that sharing results of all research is important. STAT has an interesting analysis of this: https://www.statnews.com/2015/12/13/clinical-trials-investigation/

Thanks, Joe! This is why I love to blog – to get multiple points of view (with footnotes and further reading 🙂