The Council of Medical Specialty Societies and the Association of Academic Medical Colleges, with support from the Gordon & Betty Moore Foundation, are hosting a webinar series focused on COVID-19 patient registries. They are being offered free and open to the public.

The second in the series took place on July 8 and addressed the following questions:

- What is required to accelerate availability and access to electronic data sources within registries, highlighting examples from Covid-19?

- What data sources, traditional and novel, are captured and what is their potential to be used for real world evidence?

- What commitments and resources are needed to access data in real time to address organizational and research needs?

Atul Butte, MD, PhD, Chief Data Scientist, University of California Health, served as the moderator. Panelists included:

- Tellen D. Bennett, MD, MS; Section Head, Informatics and Data Science; Associate Professor, Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado School of Medicine; Attending Physician, Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, Children’s Hospital Colorado Director, Informatics Core, Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (CCTSI)

- Andrew Ip, MD, MS; Outcomes and Value Research Division, John Theurer Cancer Center; Hackensack Meridian Health

- Subha Madhavan, PhD, FACMI; Chief Data Scientist, Georgetown University Medical Center

- Jessie Tenenbaum, PhD; Chief Data Officer, NC Department of Health and Human Services

I jotted down quotes, as accurately as I could, hoping to inspire people to watch the webinar if they want to learn more. Transcription errors are mine.

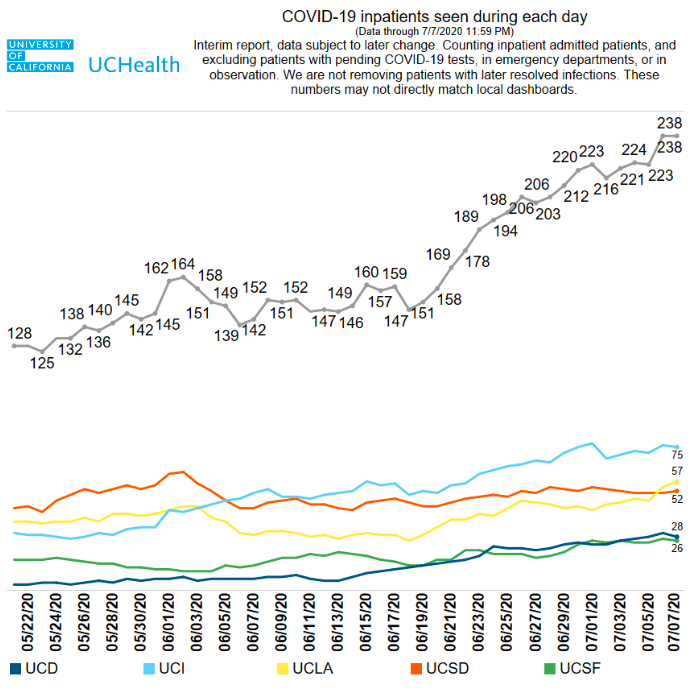

“I think it’s important to disseminate this data into the public because for most people, COVID is still an invisible disease…When we are talking about registries of the future it means putting the numbers all the way out to the patients.”

– Atul Butte on why UC Health releases daily updates on Twitter

“The registry of the future should come with sample code so that programmers of the future can quickly get to this kind of data.”

– Atul Butte talking about his vision for patient registries even as he and his colleagues deliver on a gear-grinding pivot to deliver daily COVID updates from UC Health’s five academic medical centers

My thoughts: I appreciate how transparent and open-research-oriented the UC Health data system approach has been under Atul’s leadership.

“There are well-intentioned bad actors in every system — people who want to do the right thing but don’t know how. That’s why education and training in advance of a crisis is so important.”

– Subha Madhavan

My thoughts: This goes straight to one of the points I hope we can make in the August 12 webinar I’m moderating focused on patient-generated data: We need to train EVERYONE in the importance of good data collection and systems maintenance. An informed citizen-science population is an excellent bulwark against chaos during a health crisis, at a personal or societal level.

For example, the Body Politic was organized two years before the pandemic hit and its members were able to create a COVID-19 research initiative when the situation required it. I have seen this happen over and over in the personal science movement AND in the peer-to-peer health care movement more generally. We should all work towards a future where everyone has a basic understanding of how to track symptoms and work with other people to solve problems, for example, so that when we need them they are ready.

“If it’s reported to us as a case [by a provider or local health department], it’s a case.”

– Jessie Tenenbaum, in answer to a question about their definition of a COVID19 case

North Carolina, it should be noted, only counts cases that have been confirmed by a test. They do not allow self-reported cases to be counted in their data collection.

My thoughts: Wow, is that sobering. Or is it inspiring? I can’t decide. It certainly points to the imperfect, circle-of-trust nature of public health reporting.

“My brain is divided into a public health side and an informatics side. I remind my informatics colleagues that our goal should be: How fast can we make something useful with this data? Not: How perfect can it be?”

– Tell Bennett

My thoughts: Another inspiring reminder for citizen-scientists who “make do” with the data systems they have. If the tracking they are doing is useful, then they should keep going.

“We now try not to work weekends ourselves, as we did at the beginning of the pandemic. We also try to not overwhelm key people so we can go back to them later.”

– Andrew Ip, responding to a question about burnout

My thoughts: A shared, collective leadership model reminds me of what I’ve learned about Navy SEAL training. Each team member has a specialty, but each one is also ready to step up and lead if one of their team members has to fall back. Here’s a Harvard Business Review article that discusses how the SEALs decided to pivot in the post-9/11 reality of different challenges than they’d seen before. They now embrace collaboration and learning from the ground up. How might we bring that frame shift to data collection and pandemic response?

Again, this is a tiny sample of the insights I gleaned from this stellar group. Catch up by reading the tweets (#COVIDregistries) or watch the full 90-minute webinar:

And stay tuned for details about the August 12 panel. We will announce the panelists and other details soon!

*Note: I updated Jessie Tenenbaum’s quote at 1:30pm ET thanks to a clarifying tweet from her.

If you’ve gotten this far down the page: Congrats! You are a full-fledged health data geek.

But seriously, thank you. This is a quick sampling of the many brilliant insights shared during the 90-minute session and I hope my post inspires you to watch and see all of the quotes happen in context.

Jessie Tenenbaum tweeted an addition to her quote, which I added above, and asked if the clarification changed my thoughts.

In a word: No.Update: Yes! And I updated the text above to reflect it.When I was listening to how she and her colleagues at the state level were helping clinicians, hospitals, and local health departments get their data houses in order (bravo again to their public-private partnership), I understood that it was a multi-faceted challenge that relied on all the parties to do the best they could with the resources and information they had. And I’d like to include patients and citizen-scientists in that circle of trust and understanding.

As I’ve been exploring patient-driven data registries, I’ve been hearing caveats from grassroots epidemiologists and investigators, poor-mouthing their own work. I want them to see that the whole system is imperfect and although we wish we had the resources to investigate every case, fact-check every data point, dot every I, etc. we cannot. We gather the data as best we can and look for patterns that can help other people navigate in the darkness of this terrible situation.

I think it’s both inspiring AND sobering to contemplate the trust that is involved in taking in data that you yourself cannot verify.

What do you all think?