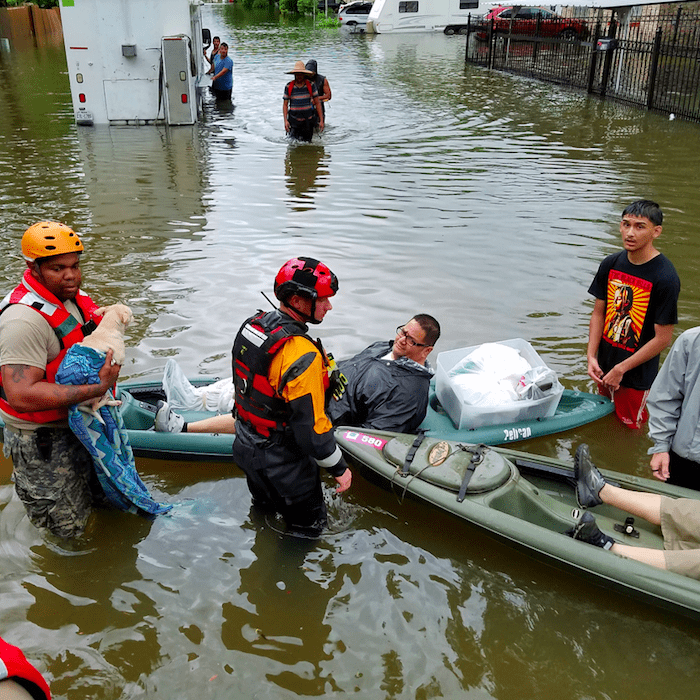

It’s inspiring to watch the “Cajun Navy” of fishing and pleasure boats rescuing people in post-Hurricane Harvey Houston, along with the National Guard and other officials. I’m always on the look-out for examples of people pitching in to help each other and solve problems, whether in peer-to-peer health care, the Maker movement, or evacuating a plane, so I loved the article that David A. Graham just published in The Atlantic on why ordinary citizens are acting as first responders in Houston.

Read what Craig Fugate, former head of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, told Graham in 2015:

“We had almost by default defined the public as a liability. We looked at them as, We must take care of them, because they’re victims. But in a catastrophic disaster, why are we discounting them as a resource? Are you telling me there aren’t nurses, doctors, construction people, all kinds of walks of life that have skills that are needed?”

Replace “public” with “patients” and read that through again. Why is health care discounting ordinary people as a resource? When a personal catastrophe hits, such as a life-changing diagnosis, how might we help people turn to our own “Cajun Navy” of fellow patients and caregivers who can provide vital advice and information? Why, when health systems need reform, do we fail to listen to patients and caregivers, who have a wealth of experience and could contribute to positive change?

Another quote from The Atlantic article (emphasis mine):

“When you step back and look at most disasters, you talk about first responders—lights and sirens—that’s bullshit,” Craig Fugate, who headed FEMA during the Obama presidency, told me in 2015. “The first responders are the neighbors, bystanders, the people that are willing to act.”

That underpinned “whole-community response,” the principle around which Fugate organized FEMA during his eight years in office. (Long only recently started on the job, having been confirmed in June.) The basis for whole-community response is that, while the government simply can never provide a response as quickly as needed, a top-down response from the government isn’t the best answer anyway. Local people know much better what they need, and they benefit from being involved.

A top-down response in health care is not always the best answer either. “Locals” (aka patients and caregivers) would benefit from being involved in health care decision-making, particularly when it affects them the most.

We are consistently leaving half the team on the bench in health care and that needs to change. Let’s create a “whole-community response” in health and health care. I’d welcome your ideas and comments below.

Featured image courtesy of the Texas National Guard.

I love everything about this post, Susannah. Excluding the person who lives with the disease 24/7 makes no sense. If someone goes to bed with a disease and wakes up with the disease they should be seen as a part of the team in their own care. No one knows their experience better than them, they are essentially their own first-responder and could, in certain situations, be someone else’s first responder. Let’s use what we’ve got!

Thanks! When I was at HHS, I convened a meeting with colleagues at NASA and UTMB in Houston and Galveston to talk about how to build capacity for sustaining human life in extreme environments, such as in space or after a disaster, when there is no power and nobody coming to help right away.

One participant in that meeting, Dara Dotz, is the co-founder of Field Ready, and the Human Factors Lead for Made In Space, Inc. She told stories about being a first responder post-earthquake in Nepal and how important it is to involve local people in creating the solutions to the problems they face. It’s not just a feel-good, everyone-on-board exercise. Locals know where to find supplies. Locals who help design and build the solution will know how to fix it when it breaks, long after the first-responders go home.

Other people at the meeting told stories about wintering over in Antarctica — the one doctor on site had to learn dentistry since he’d be on call to pull a tooth if necessary. We talked about the shared perspective of a clinician on an Army base and one serving astronauts. Everyone agreed that a primary goal for each of our organizations was to build up “local” capacity to innovate and solve problems, meaning the people in the situation, whether that’s in post-hurricane Texas or on a mission to Mars.

That’s what health care is like for most of us. Often, especially if it’s the middle of the night, there’s nobody coming and you have to solve the problem yourself. The internet, if you’re connected to it, can be a lifeline. How-to videos, discussion forums, Twitter, Facebook — these are all resources that patients and caregivers contribute to and tap into. That’s what gives me hope.

And yet. Not everyone knows about the power of peer health advice. How can we publicize this resource that’s hidden in plain sight?

Thank you for highlighting this issue which is dear to me. I believe we’d be much further along if we genuinely listened to and invited “patients” and consumers into the conversation to help us develop strategies and solve problems. I invite you to consider my blog on this topic. http://huff.to/2aK3bXS

Fabulous article, Lisa! Thanks so much for sharing it. Everyone: please click through and read it.

What’s needed is a grassroots approach, all-the-time and globally – more than just helping one’s neighbor during such catastrophic events. We need citizen-science, patients helping patients to manage chronic disease. Such thinking could turn cancer into a chronically managed illness. Peer-to-peer, isn’t it obvious?

Preach it, brother!

All wonderful ideas and I especially believe in the idea of offering peer support by sharing experiences. For example, someone who has had a health condition coaching or offering support to someone newly- diagnosed with the same condition.

The challenge I see with peer-to-peer sharing of health information is the abundance of misinterpretation, unfiltered, inaccurate health information. Our global health literacy is very low. Just today another doc told me one of her pregnant patients believed that if she ate greasy foods, the baby would “slide out easier”. Her grandmother told her this. How could we combat this?

I cross-posted this to LinkedIn and Medium in the hopes of sparking conversation on those platforms and have received a few comments & discovered another article I wanted to share here since this site is my outboard memory:

On LinkedIn, Ray Wright commented:

“About 15 years ago, a network of pharma reps joined with the Rhode Island EMA for a healthcare disaster prep drill using this Stone Soup approach. The results exceeded all expectations. (See https://apha.confex.com/apha/132am/techprogram/paper_91092.htm.)”

And Angelique Russell wrote:

“Elsewhere on LinkedIn I was just citing the fact that medical care only impacts 10-15% of health outcomes, the rest is social determinants (education level socioeconomic status, environmental factors, occupation, etc.). Ordinary people can certainly have extraordinary impact on the health of their loved ones and even their community.”

On Medium, my friend Nadav Savio applauded the post (the new “like”) and I was reminded that he’s done some work in this area of community resilience. I checked out some of his other recent recommendations and found this wonderful essay by a dad whose daughter broke her ankle — click through and you’ll see why it’s relevant: OMG

On Twitter, Clay Forsberg shared his Open Letter to Healthcare’s C-suite that contains many insights, but I’ll just pull out this devastating line: “I assumed there would be a ‘we.’ There is no ‘we.'” (Referring to his hope that the clinical team would involve him in the work of getting better.)

And E-patient Dave shared with me Victor Montori’s tweet about a review article looking at Type 2 diabetes online communities. One reply to that tweet repaid every time I go down the rabbit hole of following replies on Twitter, linking to a speech by Wendell Berry: Health is Membership. I could close my laptop for the day and be satisfied with what I’ve learned from that essay.

I love reading obituaries, so the New York Times Magazine’s annual “Lives They Lived” is a series I savor for weeks. Today I read the remembrance of Henry ‘Enrico’ Quarantelli who “proved that disasters bring out the best in us.”

One quote caught my eye, from Rebecca Solnit’s book, “A Paradise Built in Hell,” so, nerd that I am, I found the 2009 NYT review, which calls it “an investigation not of a thought but of an emotion: the fleeting, purposeful joy that fills human beings in the face of disasters like hurricanes, earthquakes and even terrorist attacks. These are clearly not events to be wished for, Ms. Solnit writes, yet they bring out the best in us and provide common purpose. Everyday concerns and societal strictures vanish. A strange kind of liberation fills the air. People rise to the occasion. Social alienation seems to vanish.”

That resonates with my own experience of illness and caregiving, as well as the testimony I’ve heard over the course of my career from other people who find themselves in the crucible of a health crisis.

For example, I remember Laurie Strongin talking about how, when her son Henry was gravely ill, she and her husband made a home out of an 8×10 hospital room. There was no confusion about what was important, about how to be a good parent, about what the priorities were — being together, being present, finding joy in small moments.

I’m not a “cancer is a gift” person myself, but I do try to soak up the wisdom and perspective that people share when they write about the experience of a life-changing diagnosis. Because why not try to bring that into your own life? Why not look for ways to join the rebuilding of a community, a home, a life even if it’s not yet in crisis?

An article recently flickered across my screen and I wanted to capture it here, since it’s relevant:

How your social network could save you from a disaster, by Daniel P. Aldrich and Danaë Metaxa (July 16, 2018)

An excerpt:

“We looked at three different types of social ties:

– Bonding ties, which connect people to close family and friends

– Bridging ties, which connect them through a shared interest, workplace or place of worship

– Linking ties, which connect them to people in positions of power.

While our research is currently being revised for resubmission to a peer-reviewed journal, we feel comfortable arguing that, controlling for a number of other factors, individuals with more bridging ties and linking ties – that is, people with more connections beyond their immediate families and close friends – were more likely to evacuate from vulnerable areas in the days leading up to a hurricane.”

A link within that article led me to:

Recovering from disasters: Social networks matter more than bottled water and batteries, by Daniel P. Aldrich (Feb. 13, 2017)

An excerpt:

“A Japanese colleague and I hoped to learn why the mortality rate from the tsunami varied tremendously. In some cities along the coast, no one was killed by waves which reached up to 60 feet; in others, up to ten percent of the population lost their lives.

We studied more than 130 cities, towns and villages in Tohoku, looking at factors such as exposure to the ocean, seawall height, tsunami height, voting patterns, demographics, and social capital. We found that municipalities which had higher levels of trust and interaction had lower mortality levels after we controlled for all of those confounding factors.

The kind of social tie that mattered here was horizontal, between town residents. It was a surprising finding given that Japan has spent a tremendous amount of money on physical infrastructure such as seawalls, but invested very little in building social ties and cohesion.

Based on interviews with survivors and a review of the data, we believe that communities with more ties, interaction and shared norms worked effectively to provide help to kin, family and neighbors. In many cases only 40 minutes separated the earthquake and the arrival of the tsunami. During that time, residents literally picked up and carried many elderly people out of vulnerable, low-lying areas. In high-trust neighborhoods, people knocked on doors of those who needed help and escorted them out of harm’s way.”