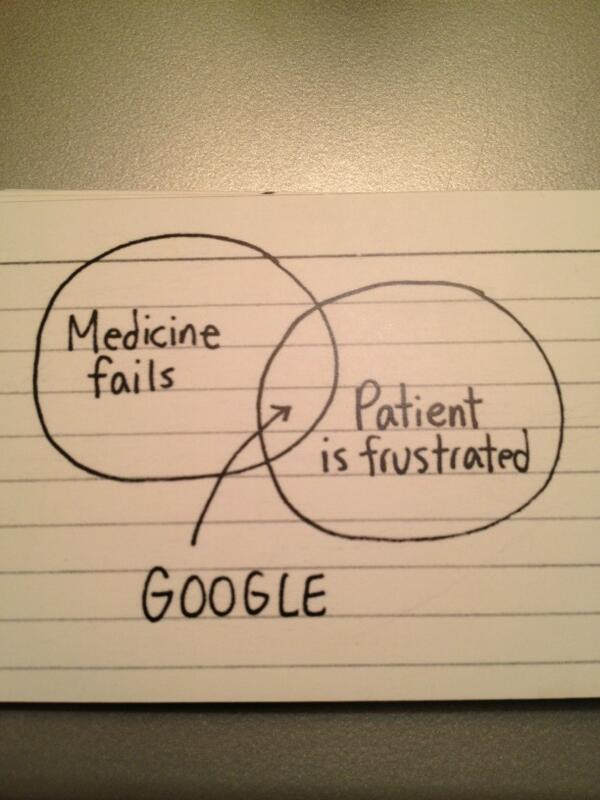

Jessica Hagy is one of my favorite social commentators, so I was thrilled to meet her in person at the 2010 Mayo Transform conference, curated by David Rosenman. Here is one of her cartoons from that event:

I have shared the image on Twitter a few times, including today, when I wrote that I’d add “community” to “Google” as an option for patients. Jordan Safirstein, MD, (aka @CardiacConsult) replied, “I would write ‘2nd Opinion’ – with more available telecom – pts will be able to get informed 2nd opinions easier.”

What do you think? I know it’s just a cartoon, but it captures something, and I’d love to discuss it if it inspires (or incites) you. Is technology, particularly social media, causing medical complaints to go up (as one article suggests)? Or is it a means of expression for broader cultural change?

Agree – this cartoon summarizes so many fundamental cultural changes wrought by the “simple” accessibility enabled by Google’s “focus on the user and all else will follow” (#1 in the list of “10 things we know to be true”). The user is in charge in so many places now, but not yet in medicine. Even the language reveals an external locus of control: “medicine.” One patient doesn’t engage with medicine. One patient engages with one provider, clinic, hospital staff, etc. At the heart of each of these opportunities for success or failure is a relationship between 2 humans. Historically, 1 of those humans hasn’t been the other’s equal in terms of access, influence, control, decision-making. By opening the access door, Google invites the user back in at an empowered position.

Yes! I hadn’t seen that list before so I’ll share it here:

Ten things we know to be true

Didn’t also know about the ten things we know to be true.

I also have remarked that it is not only when medicine fails that we consult google: now, we do for almost everything. From the weather, to find addresses, to check on health information, to find health care providers.

From discussions and observation, I estimate that at least four patients in ten (in my country Greece) go to an important medical appointment thoroughly informed by Dr. Google… They say that information eases their anxiety, makes them able to think of questions to ask, empowers them with the example of other patients… However, before a diagnosis, very few would ask peers online for information or advice…It seems that those connecting on line are patients already living for some time with the disease rather than newly diagnosed…

In my experience, people don’t just head to Google when medicine fails or when they are frustrated. The culture of health and healthcare and how we access it is changing–it has become normal, even expected for people to look up health information online. I see it even with families with whom I have a really good relationship, families that can easily access me by email. It has changed how I practice medicine: not only do I use the Internet more for educating people, I now ask people more about what they already think or know when they come to me.

True! Great insight. That is what HAS changed in the past decade — it has become normal behavior to research health issues online, not transgressive behavior.

That little drawing is fun and thought-provoking. It makes me think of two things just now.

1. Trudy Lieberman just published a post with examples of patients being unhappy when medicine did not fail (meaning, the care offered was actually pretty sound, although it’s possible the communication was sub-par and that’s a type of failure I suppose.)

http://www.cfah.org/blog/2014/has-patient-centered-health-care-run-amok

2. What about “medical failures” which don’t generate much frustration because patients don’t notice them. In my line of doctoring, I come across many older patients who are getting sub-optimal care, but they don’t realize it so they aren’t frustrated, and they may not go looking for Google or community. For instance, so many people with dementia are still taking sleeping pills! Or people are shunted into a high-intensity medical approach when something less intensive might be just as good, but they weren’t offered the choice.

I wouldn’t be surprised if information technology, including social media, has increased complaints. I’m sure many of these complaints are legit and are needed in order to goose needed changes. But inevitable that there are downsides.

I find this cartoon to be perplexing. As a primary care physician, I would love for my patients to google more. Please, google diabetes-friendly recipes or good stretches for foot pain. Seek information early and often. I do not think participants in the e-patient movement realize that health care providers are much more frequently in the position of trying to find a way to engage people in their health, when they have other pressing priorities in their lives, than the reverse.

Thanks so much for making the jump from Twitter. I always appreciate your perspective as a clinician serving a different population than the one that is already deeply engaged in their health. Maybe we can ask Jessica Hagy to create a new series of editorial cartoons about that aspect of health & tech!

Fellow indexed fan here.

I wanted to follow up a bit on the CFAH article Leslie mentioned above, as it is focused around a significant document, Crossing the Quality Chasm (see here), published by the IOM over 13 years ago. Today’s ACA (i.e., Obamacare) takes a number of cues from this document, including its root notion of patient centered care.

If one were to oversimplify for the purposes of a brief blog comment (*cough*), one might describe the IOM’s proposed approach thusly:

1. Patient outcomes should be safe, effective, efficient, personalized, timely, and equitable

2. To achieve said outcomes, we need high performing patient centered teams

3. To have said teams, we need organizations that facilitate this work

4. To facilitate this work within organizations, we need a supportive environment (<–this is where reforms come in)

The IOM details a number reforms needed within the health care system to achieve better outcomes, and provides clear direction for changing how health care is delivered. At the same time, it remains focused on formal systems of care (i.e., patient centered teams comprised of health and service providers) and never specifically highlights the actual patient role within redesigning care.

All this to say the Indexed cartoon highlights one element of a much larger conundrum in health care: how to integrate and support the marriage of informal and formal systems of care to truly create a patient centered experience. I've said it many times before: healthcare is 80% social, and 20% clinical (that's not scientific; just my own perspective), and the increasing ability/interest of people connecting with the help of tech can provide a huge assist here.