Atul Gawande can shine a bright spotlight, even with just a few tweets. On Saturday he linked to an article about new social media guidelines for physicians which states:

Aside from not “friending” patients [on Facebook], the guidelines also recommend the following to physicians:

• Don’t use text messaging for medical interactions, even with established patients, except with caution and the patient’s consent.

• Only use e-mail within the context of an established relationship with a patient, and with that patient’s consent.

• Establish a professional online profile so that it appears at the top of a web-based search, above any physician rating site.

• Discourage e-mail or on-line communications with individuals who are not patients, instead referring them to make an appointment or visit an appropriate health provider.

• Manage their digital image, including refraining from posting about personal social activities that might not reflect positively or providing less-than-measured comments on Twitter, blogs, or in response to online articles.

I captured a bit of the online conversation in a Storify, tweaking the title to characterize it more broadly: Doctor-patient online communication. I didn’t want it to scroll away and be lost, since I think the reactions capture a moment in time. [Storify shut down in 2018 and I didn’t save that collection when I transferred to Wakelet.]

Update: read the guidelines released by the American College of Physicians.

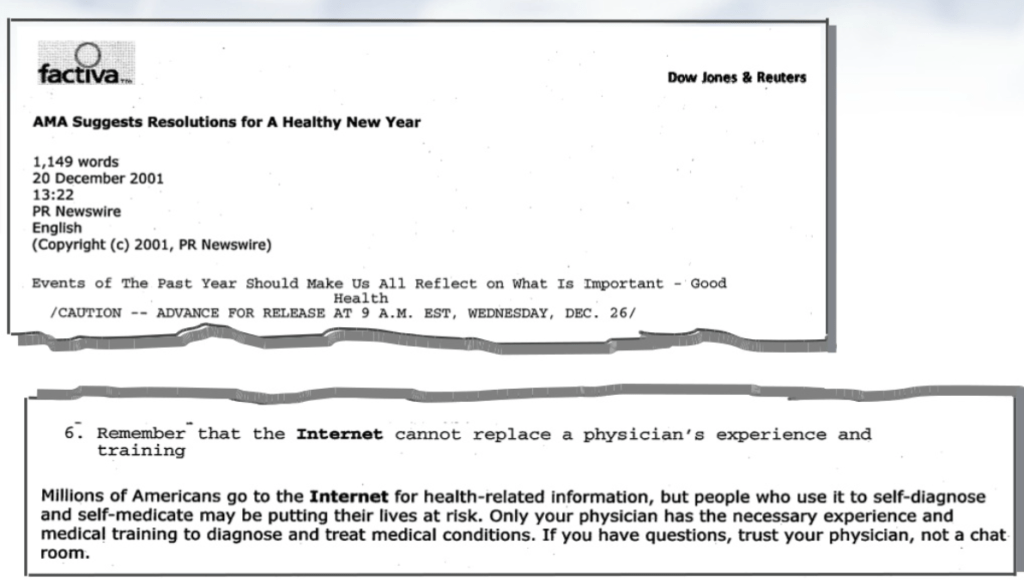

Speaking of moments in time, I received an email on Saturday from Arash Najibfard, an undergrad at UCSD, who’d found my 2007 interview on NPR, “Patients Turn to the Internet for Health Information,” and asked for a link to the 2001 AMA press release warning people about the dangers of going online for health advice. Happily, I saved a print copy of that release and a PDF lives on the e-patients.net blog: (that’s now a broken link but I’m adding an image below.)

One of the recurring themes of my work is to remind people that today is just a moment in time, that things will change — that things have changed even if you personally can’t see it yet.

All of these conversations — this weekend’s tweets, the 2007 NPR story, the 2001 press release — are simply snapshots of a certain population at a certain time. Never assume that what you are seeing or experiencing is everyone else’s reality. Look to data to give you a clear picture. Look to leaders in the field to give you a sense of where things are going. And in the case of online communications about health, that sometimes means e-patients, not clinicians.

I’m not saying who’s right, who’s wrong, or what’s the right policy. I’m saying: Don’t assume. Keep your eyes and ears wide open. That’s what I learned from Tom Ferguson, MD, one of my teachers, and from my grandmother, Rosalie Yerkes Figge, who I talk about at the start of the NPR interview. They passed away the same week in April 2006 and I miss them every day.

Featured image of a string of lights by Ted Eytan, MD.

Thanks to your post today, I just found this one.

> things have changed even if you personally can’t see it yet.

The early e-patients.net blog, created by Doc Tom Ferguson a year before his demise, included a “quote-a-matic” that would spit out different quotes. As a change-spyer, I most liked this one, and have made a career out of illustrating it in speeches:

For those who aren’t convinced, see what Tim O’Reilly said on TED (citing Gibson) about early signs, e.g. his 1992 complete guide to the entire web. (There were 200 websites.)

Ferguson attributed the quote to “futurist William Gibson,” the novelist who according to Wikipedia Gibson coined the term cyberspace. In 1982. Dat’s vision, baby!

It all leaves me thinking that there’s a lot to be said for noticing new patterns as they start to emerge. Saves tension later worrying about why the earth is shifting.

(Bonus question: Gibson imagined “cyberspace” a decade before O’Reilly cataloged all 200 websites. What can we imagine will be happening in 2024 that’s just a glimpse of the next big thing?)