I learn from every conversation I have with Cambia’s outgoing CEO, Mark Ganz — lucky for everyone, we recorded this latest one!

Here’s a quote I loved:

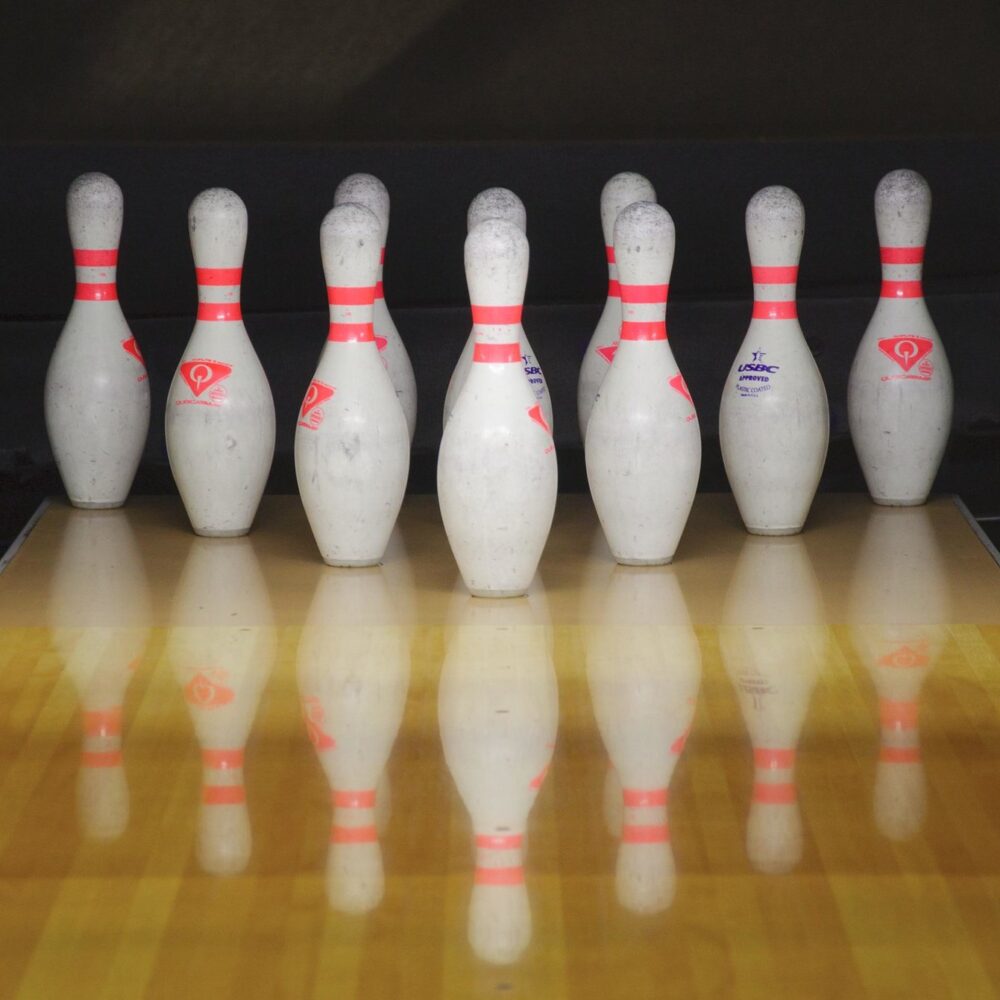

“A wise person once told me that the way to make progress in some ways is to think of a bowling analogy. You don’t try to knock 10 pins down by having the ball hit all 10 pins at once. The ball has to hit the center pin and at the right way, and then the center pin is what takes out the rest of the balls. That’s how you get a strike.

I think that that’s true for transformation of an industry, is that you must pick your center pins. When you think about the poignancy, the importance of the experience that individuals and families go through with serious illness and if you could transform that to be something that is truly focused on the needs of the individual.”

And another:

“In my career, there have been things that have had the effect of breaking up ice flows, cracking them open. So you can navigate your ship through to make progress, but you also have to still respect that the ice is still all around you and that it could simply crush your ship as you try to move it through. You have to go forward with courage and with that sense of vision of where you’re trying to go.”

Read the transcript and/or listen to our conversation:

What would YOU say have been some events that have broken up the frozen tundra of health care? Where has your ship gotten stuck — or crushed — in the ice? Or, switching tracks, when have you hit the center pin? Let me know in the comments below.

Image: “Standing Tall” by Dwayne Madden on Flickr.

Love this analogy. For me the centre pin was the work that many people contributed to on formalizing #PatientsIncluded criteria for medical conferences in 2015 (https://patientsincluded.org/). It all started with Lucien Engelen’s famous blog post in 2010 of course but in my specific field of ALS/MND I had tried various methods to encourage more patients to the main annual conference without much success, and ditto for having the most interesting stuff live streamed.

As the number of medical conferences grew to include those run by the BMJ, EyeForPharma, and even HIMSS, it felt like more of a movement with those other pins knocking themselves down voluntarily. Next up was a critical meeting around these issues with Cathy Collet and other ALS/MND advocates where we decided to take our own steps and initiated the ALS/MND Patient Fellows program (https://www.alspatientfellows.org/), a competitive program where patients / caregivers would be supported to attend the meeting in person (https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2018/03/27/paul-wicks-patientsincluded-is-harder-than-it-looks-but-worth-it/).

It started off small but has grown to take a more central role, until, while I hesitate to say the final strike has been landed, this year partly due to the progress made so far and the inevitability of COVID-19 on medical conferences, one of the patient fellows, Bruce Virgo, made the first non-scientist patient plenary talk (https://twitter.com/BVirgo1/status/1336419922394697733). Now when I read peer-reviewed articles by researchers with titles like “How the 10th ISDM Conference Got to Qualify as “Patients Included™”: Insight from Inside” (https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40271-020-00464-1) I’m just about ready to say we’ve knocked down those pins. Much like bowling though, those pins do rerack themselves pretty quickly when you turn your back, but once you’ve got the technique down you know you can hit that sweet spot again and again.

Wonderful example! Yes, including patients and caregivers in public conversations and meetings about the issues they face (and are experts on) is definitely a “center pin.” Because once they are in the room, in person or virtually, everyone can see how much value they bring.

And you’re absolutely right about the pins reracking themselves when your back is turned (I lol’d) but so too do our bowling balls pop right back up to knock the pins down again.

Like Paul, I also love the “center pin” analogy! For me, there have been “center pins” in my own way of seeing things, as well as in how I approach my own work of achieving change.

Examples of the former category include the conference Stanford Medicine X and the wonderful community around it (https://medicinex.stanford.edu). Their YouTube channel is endless source of knowledge and inspiration: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCK1chhgXNHf7iB5mlqzXODA

Another example that knocked down all of the pins of the way I saw things is the article in NEJM “We Can Do Better — Improving the Health of the American People” (https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmsa073350). In it Steven Schroeder demonstrates that our health is made up by contributions from healthcare, behavioural patterns, genetic predispositions, social circumstances, and environmental exposure. My thinking about health and healthcare was forever changed when I learned that healthcare’s contribution is no more than 10%!

In my own work, my “center pin”, that has proven the most powerful tool, has to be the word “spetspatient”. It is *sort-of-but-not-quite* a Swedish equivalent to e-patient and I coined it in February 2016. A Google search today yields 6,500 hits, which is not bad for a word that has only existed for a couple of years. Read more here: http://www.riggare.se/2019/06/09/what-is-a-spetspatient/ and here: http://www.riggare.se/2020/12/06/draft-version-of-the-spetspatient-framework/

I love that, Sara! Your introduction of the word spetspatient is a paradigm-shifter, which is another way to think about a “center pin.” What knocks people off-balance and makes them see the world from a new angle?

Another center pin that I’ve seen targeted for transformation: Maternity care. I’ve learned a lot about system change by following the work being done by Amy Romano (@MidwifeAmy on Twitter). See, for example: Let’s Midwife the System. Once women (and their partners) get a taste of good care, they may not settle for less as their lives progress.

That reminds me of my own experience with being a food-allergy parent. My son’s first school embraced us, embraced the opportunity to learn about food allergies and how to keep kids safe. As I wrote in my essay, “Back to school with food allergies,” the school director, Jim Clay, showed us what is possible:

“I tasted what it would be like to live in a world where differences were celebrated. I now had a mental model for a school environment that was truly safe, that truly had my child’s — every child’s — best interests at heart. It strengthened my resolve when I later encountered school administrators and teachers who did not know how to create such an environment. I could tell them what it looked like, how we could achieve it, because I had seen it, not just in my minds-eye, but in practice, under Jim’s leadership.”

Circling back to the center pin image: I think radical inclusion was the center pin in the School for Friends model. They approach education of each child with that child’s needs at the center in the same way that some health care systems are attempting to do. By focusing on inclusion and the celebration of differences, everything else fell into place. Safety protocols became obvious practices.

Would you say that open health data is a center pin? Or maybe Mark Ganz’s ice floe break-up is a better image?

When I messaged Amy Romano to let her know I’d mentioned her work, she wrote back: “Finding the e-patient white paper was a pin moment, as was learning the term ‘salutogenesis’.”

She is referring to the paper that Tom Ferguson, MD, was writing when he died in 2006. It was subsequently completed and published by his colleagues (including me):

e-Patients: how they can help us heal health care

Meantime, to save you the search: salutogenesis is essentially a medical model that supports health, including emotional well-being (as opposed to pathogenesis, a model which focuses on causes of disease).

I’m hoping Amy stops by to share more from her perspective.

I love this concept and the conversation it has brewed. And thank you, Susannah, for bringing the pregnancy experience in.

For me and the advocates I have worked with, defining and framing “physiologic labor and birth” was pivotal and absolutely a center pin. This was framing we began to use in the early 2010’s. The book I co-authored, Optimal Care in Childbirth: The Case for a Physiologic Approach came out in 2012, the same year the three midwifery organizations in the U.S. released a consensus statement on Supporting Healthy and Normal Physiologic Childbirth. These and other resources reframed the approach to care to say that supporting and getting out of the way of the normal physiologic process should be the first-line approach to care, with medical intervention added judiciously based on evidence and shared decision making. This was not and still is not the American way of thinking about birth, but the concept and language have become much more mainstream and are now driving major national and regional efforts to reduce the cesarean rate in low-risk births (a Joint Commission core measure.) I am currently working on a learning module for maternity nurses that will be implemented in a multi-center QI program at Ariadne Labs. The focus on physiology spurred a realization of the need for much more and better evidence on normal physiology. There is now much, much more research evidence to actually help us understand normal physiology and how different interventions may influence endogenous systems and innate behaviors, and a major global initiative to investigate all of this further including epigenetic and microbiome effects. Certainly, some of this progress would have come regardless, but reframing from “natural” or “normal” (both perceived as judgmental) to “physiologic” (perceived more as fundamental and scientific), I do think broke open the dam.

I am now doing my best to force the same kind of awakening around the concept of “primary maternity care.” There is no concept of this in this country – no consensus about what services, education, and support are fundamental for healthy pregnancy and birth, what basic access points must be available in every community, etc. As a result, we have massive expanses of this country that have no maternity access at all, and we are spending hand over fist on preventable complications while disincentivizing use of midwives and birth centers despite CMS’s own evidence that they improve outcomes and reduces costs. I do feel like the lingo is catching on, and people’s lightbulbs are going off around primary maternity care. ACOG and others in the meantime have developed consensus standards of “Levels of Maternal Care”, which includes birth centers. The concept so far has only been applied to facilities but some momentum is building to begin to define levels, core competencies, and integration frameworks for prenatal and postpartum care. So there’s an opportunity to define (and most importantly, optimize) primary maternity care within that work.

I am excited that in 2021 I will be working on a community-led initiative to begin the process of defining it using a equity-focused design process. Having community members take the lead and centering health equity are certainly made possible in part by the parallel progress others have discussed in this thread to ensure patients are at the center and included in all levels of policy making – along with the incredible progress and leadership in understanding the role of racism in our healthcare system. In fact, I think the “racism not race” framework for discussing health disparities is another center pin that tipped in recent years and has enabled progress to accelerate and investment in new models and ideas.

Thanks as always for getting me thinking! Be well.