Tom Ferguson, MD, gave me this robot in 2002, part of the first (and only?) fourth class of awardees of the Ferguson Report Distinguished Achievement Awards. I have kept it on or near my desk ever since.

Reading Tom’s old essays, even as far back as the 1970s, is humbling. He foresaw so much of the world we live in now. I owe him a great debt since part of his vision was to see something in me that I didn’t yet see in myself. He believed in me.

Here is the introduction to the e-patient “white paper” (PDF) he was writing at the time of his death in 2006, which explains his attachment to robots:

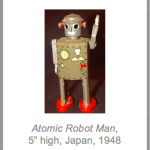

I collect old toy robots. My Atomic Robot Man robot (Japan, 1948), shown [at right], is a personal favorite. For many years I didn’t understand the powerful hold these dented little metal men maintained on my imagination. One day I finally got it: They show us how the culture of the 40s and 50s imagined the future. Cast-metal humanoid automatons would do the work previously supplied by human labor.

I collect old toy robots. My Atomic Robot Man robot (Japan, 1948), shown [at right], is a personal favorite. For many years I didn’t understand the powerful hold these dented little metal men maintained on my imagination. One day I finally got it: They show us how the culture of the 40s and 50s imagined the future. Cast-metal humanoid automatons would do the work previously supplied by human labor.

That wasn’t how things turned out, of course. By making more powerful and productive forms of work possible, our changing technologies made older forms of work unnecessary. So instead of millions of humanoid robots laboring in our factories, we have millions of information workers sitting at computers. We didn’t just automate our earlier forms of work. It was the underlying nature of work itself that changed.

In much the same way, we’ve been projecting the implicit assumptions of our familiar 20th Century medical model onto our unknown healthcare future, assuming that the healthcare of 2030, 2040, and 2050 will be much the same as that of 1960, 1970, and 1980. But bringing healthcare into the new century will not be merely a matter of automating or upgrading our existing clinical processes. We can’t just automate earlier forms of medical practice. The underlying nature of healthcare itself must change.

This is not some technoromantic vision of an impossibly idealist future. It is already happening. The changes are all around us. As we will see, the roles of physicians and patients are already changing. And our sophisticated new medical technologies are making much of what the physicians of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s thought of as practicing medicine unnecessary. Financial constraints are making the old-fashioned physician’s role unsustainable. And millions of knowledge workers are emerging as unexpected healthcare heroes.

When they, or a loved one, become ill, they turn into e-patients—citizens with health concerns who use the Internet as a health resource, studying up on their own diseases (and those of friends and family members), finding better treatment centers and insisting on better care, providing other patients with invaluable medical assistance and support, and increasingly serving as important collaborators and advisors for their clinicians.

We understand that this document may raise more questions then it answers. And while we are by no means ready to dot all the Is or cross all the Ts, we strongly suspect that the principal protagonist of our next-generation healthcare system will not be a computerized doctor, but a well-wired patient. Yet our formal healthcare system has done little to recognize their accomplishments, to take advantage of the new abilities, or to adapt itself to their changing needs.

Turning our attention to this promising and fertile area—which to date has somehow remained off the radar screens of most health policymakers, medical professionals, federal and state health officials, and other healthcare stakeholders—may be the most important step we can take toward the widely-shared goal of developing a sustainable healthcare system that meets the needs of all our citizens. But as the battered little robot beside my computer constantly reminds me, we are in the early stages of this process. And our current and future new technologies may change the nature of healthcare in ways we can, as yet, only vaguely imagine.

As MIT’s Sherry Turkle has suggested, instead of asking how these new technologies can help us make the familiar processes of medical care more efficient and effective, we should ask ourselves how these new technologies are “…changing the ways we deal with one another, raise our children, and think about ourselves? How are they changing our fundamental notions of who we are and what we need to do and who we should do it for? What new doors are they opening for us?”

The key question we must ask, Turkle suggests, “…is not what technology will be like in the future, but rather, what will we be like…” when we have learned to live and work appropriately within the new technocultural environments even now being created by our new technologies. For the healthcare of the future—if it is to survive—will be as novel and unexpected to those of us trained as clinicians in 20th Century medicine as today’s computer-toting knowledge workers would have been to the social planners of the 1940s and 50s. We hope that the chapters that follow provide our readers with some interesting and useful perspectives on these questions.

If you have not yet read the full paper, I highly recommend it.

I would love to hear reactions to Tom’s essay. And I’d love to hear what you keep nearby, to inspire you. Please share in the comments.

Thanks for bringing this up again. I’ve been fascinated by this white paper ever since you recommended it during that MedX Empower Me course you led.

I’ll be honest, Tom’s vision is inspiring and prescient. But I have this conflicted feeling that he is indeed describing the future of healthcare, but it’s one we’re not yet experiencing. Why is that? If I ever had a spare month or two, it’s something I’d love to research and sort out. Have you felt like that at all?

Brett,

You are right. Tom’s vision has not yet been fully realized. But it does continue to emerge.

You can catch glimpses of it, in pockets of the country, such as when Open Notes was rolled out and, “after 12 months, 99% of patients wanted to continue to have access to their notes online and none of the doctors decided to stop the practice.” (BMJ, 2015)

If I had time, I would write another post like this one:

Peer-to-peer Healthcare: Crazy. Crazy. Crazy. Obvious.

Or I’d evaluate how many of Tom’s predictions had come true.

But I’ll share some advice I recently received. Someone said to me: Your career has been a mix of analyzing things and building things. Resist analyzing. Build.

I’ll also share this memory of Tom. When he was quite ill — “bald as a cue ball” from chemo, as he put it — he came to DC for a visit. I don’t remember the details, but there had been some setback in the e-patient movement, some cutting remark by a prominent doubter, some news article that had got it all wrong.

I asked him how he was able to maintain his sunny optimism. He was smiling, even as he was a decade into cancer treatment and four decades into the fight for patient empowerment. I believe that some of his optimism might be genetic — a pioneer, entrepreneurial spirit — but his answer took no personal credit. He talked about his Zen practice, his focus on gratitude and to “be here now.” To be in the moment, at all times, is to exist in possibility.

My interpretation is that “be here now” contains the possibility that your reality — of finding a hospital that welcomes empowered patients, for example, as Tom did — is one that can animate the world.

Around the same time, I had lunch with Jim Clay, the director of the preschool my children attended, School for Friends. It is a school that not only embraces diversity, but welcomes every aspect of a new family or challenging situation as an opportunity for everyone to learn, to deepen their understanding of their role in the community.

In my food-allergy (FA) support group, I’ve read many stories of schools which exclude FA kids — either by not admitting them, by outright telling parents that they cannot guarantee an FA child’s safety, or by refusing to accommodate a family’s requests for safety measures. Jim took the opposite tack. As soon as he found out that my son had FA, he called a meeting of all the teachers and we conducted in-depth training on not only the safety issues, but the social issues of FA. He then publicized the new policies to all parents, letting it be known that FA was something we as a school community would embrace.

Most parents followed the new rules without complaint. A handful did not. They complained. They asked why they couldn’t bring XYZ food. Jim was unswerving, as were the teachers. And I felt their embrace. I tasted what it would be like to live in a world where differences were celebrated. I now had a mental model for a school environment that was truly safe, that truly had my child’s — every child’s — best interests at heart. It strengthened my resolve when I later encountered school administrators and teachers who did not know how to create such an environment. I could tell them what it looked like, how we could achieve it, because I had seen it, not just in my minds-eye, but in practice, under Jim’s leadership.

Over lunch that long-ago day, I asked Jim how he maintained his optimism, his resolve to create a school environment that was a reflection of his vision for a better world. We had been talking about parents who were resisting the FA policies, but they were just that week’s examples of people who railed against some policy or change. After 20 years, Jim had seen it all, or so it seemed to me. His answer sticks with me to this day: You just have to keep shining a light on the path. Everyone comes to it eventually.

That, to me, is at the heart of what we’re talking about when we talk about the possible future of health and health care. Tom was shining a light on the path. He was living his vision for what we now are calling patient-centered care. He was unswerving in his demand for it — he had the mental model and would not put up with anything less, but gently, with a smile.

There’s a leap of faith in all of this, I think. Both Tom and Jim set their eyes on a point on the horizon and steer toward it, like it’s the only way to go. Because to them, it is the only way. And that’s what I carry with me — that assurance, that mental model of what could be, that confidence that everyone will come to the path. Eventually.

Doc Tom had earlier sets of the Achievement Awards (in 1999) as well:

http://www.fergusonreport.com/articles/fr039904.htm

http://www.fergusonreport.com/articles/fr059903.htm

http://www.fergusonreport.com/articles/fr079905.htm

The award still motivates and inspires me as well.

Thank you!!!! I knew someone would be able to fill in the blanks. This is why I love our community — you complete me 🙂

For inspiration, I keep appreciative notes from family caregivers around. It reminds me of why I’m doing what I do, that I love doing what I do, and that it does help some people.

Tom’s vision is wonderful. This paragraph particularly struck me:

“When they, or a loved one, become ill, they turn into e-patients—citizens with health concerns who use the Internet as a health resource, studying up on their own diseases (and those of friends and family members), finding better treatment centers and insisting on better care, providing other patients with invaluable medical assistance and support, and increasingly serving as important collaborators and advisors for their clinicians.”

Yes yes yes! As a former healthcare quality researcher, I think this is the key to better healthcare that truly serves people and their families.

Agree with Brett that progress often feels slow, but we’re on the right track.

Perspective is always key. Yes it appears that progress is slow, compared to where we want to be.

In some ways the goals remain the same we discussed with Tom 20 years ago and nothing short of an immediate transformation will do to bring us there.

In many other ways, though, the changes we have experienced are nothing short of phenomenal. It is a testimony to the deep success of the changes that we don’t even notice them, just as should be for transformative technology, which must disappear from the user mindset to be efficient.

When we started working on the e-paper white paper we were really a bunch of “pirates” talking about a future where everyone would acknowledge the central role of patients and where patients would be in charge. Then the great majority of professionals working in health care would look at us and say we were crazy or, even worse, dangerous. I remember the day at the Intel Health Hero day where 1/2 of the audience of my talk, stand up and left right after I said “patient online communities are a new form of peer-reviewed publications”.

No one would dare to say openly today that patients are not central to both care and to the reform efforts, because the environment, fostered by constantly expanding technologies, has so drastically changed.

Thank you Susannah! I always learn so much from you, both about what has happened and is happening now but also about myself and how to find the path when all is dark.

I am struck by the scale aspect of things. How your children’s school was so well organized and managed and how Tom Ferguson seem to have been able to create a sort of atmosphere around himself that made people understand on a deeper level. And you write that there are places all around the US where Tom’s vision has been realized more than in other places. But how will we know when it is enough? How will we decide when we have succeeded? Is there any way we can measure, quantify or observe when people understand? Or is it like the story about a judge at some court somewhere in the US alledgedly said: “I cannot define pornography, but I know it when I see it”?

My question is: Do we need to define the “Ferguson effect”?

I hold no totems, except for what you describe as vision and “the light.” My confidence in these took infinite root during my illness, when I was keenly aware that I could not know the future, nor even the microscopic detail of how things were unfolding inside me; so I knew that my thoughts and feelings were not physical reality, they were my human *thoughts* about what I *thought* reality might be, though I didn’t know.

It’s exactly the same as the moment before I got that fateful phone call from my primary. In that moment I had Stage IV kidney cancer and didn’t know it … reality was what it was, regardless of what I thought.

Thus I approached every new scan not with “scanxiety” but with a clear sense: “Reality is what it is, whether I know it or not.” And the scan, whatever its outcome, would only make me better informed.

But maybe I need to find some totem … it will surely be something from my dead friend Dorron.

Or, in the sic transit spirit, perhaps it’s the 1938 hardcover book I laid hands on today: Arithmetic for Printers.