This post originally appeared on RWJF’s Culture of Health blog:

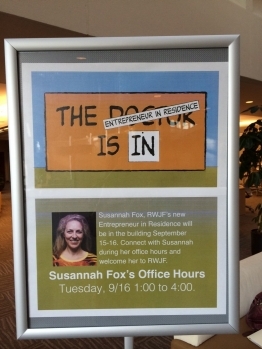

I am thrilled to begin my job as the entrepreneur in residence (EIR) at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

I am thrilled to begin my job as the entrepreneur in residence (EIR) at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

You might think that the EIR role is traditionally associated with venture capital firms, not foundations. But scratch the surface and you’ll find commonalities between the two industries. Both VCs and philanthropists have daring ambitions, place lots of bets, and hope for a big pay-off every once in a while. The difference is that a philanthropy like the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation places a priority on societal dividends, such as greater access to health care or a reduction in childhood obesity.

I also like this definition of entrepreneurship: “The pursuit of opportunity without regard to resources currently controlled.” That fits the Foundation to a T as we pursue the audacious goal of building a Culture of Health in the United States.

But how will we measure success? How will we know if our bets ever pay off, especially when we are talking about culture change? I have a story to tell that I think illustrates how a small grant can make a big difference in the world.

In 2002, Robin Mockenhaupt, now chief of staff at the Foundation, oversaw a grant to Tom Ferguson, MD, to write a white paper about what he called “the first generation of e-patients.” In one bold stroke, Tom coined the word e-patients to describe people who are equipped, enabled, empowered, and engaged in their health and health care decisions. It was an almost outlandish idea a decade ago. But Robin believed there was something there and she wanted Tom to chronicle it.

The initial grant was for a six-month project. Tom worked on it for four years, continually improving on and expanding the white paper with the help of a close circle of advisors. I think the Foundation may have given up on seeing any result from the grant. And indeed, when Tom died unexpectedly in April 2006, it seemed that his work would go unpublished and unshared.

Instead, Tom’s friends and advisors (including me) finished the white paper and published it as free PDF on e-patients.net. It sparked a conversation that continues today in policy circles, clinical settings, board rooms, and – just as important – around the kitchen table of anyone who finds themselves dropped into the maze of health care without a map.

Meantime, the word “e-patient” has become part of our lexicon. The equipped, enabled, empowered, engaged – and yes, entrepreneurial – patient has a seat at the health care table. That’s a cultural change that benefits us all. And it’s a ripple effect from a pebble dropped into the pond of the public conversation in 2002.

How might we measure the effects of small grants like the one that supported Tom’s work? How might we recognize the opportunities that seem outlandish today but will resonate far into the future?

As a researcher, I documented the online landscape and followed the trail blazed by people living with chronic and rare conditions – the alpha geeks of health care. Now, as an Entrepreneur in Residence, I hope to drop a few pebbles into the pond of culture change.

Please join us in dreaming big, setting audacious goals, and co-creating the future of health and health care. Let us know what opportunities you see and where you are placing your bets.

Susannah, while Tom had the vision and nurtured this project over years, you and other leaders saw it through to a finished product… in honor of Tom and of the e-patients around the globe who knew they were empowered before anyone else did. Thanks for your persistence and patience in making this opportunity a reality.

Robin, thank you!

It was truly my honor to be part of what Tom called the “e-Patient Scholars Working Group” (which later became the core of the Founder’s Circle for the Society for Participatory Medicine). Here’s the list of people who helped bring the paper to completion:

Gilles Frydman

Joe Graedon

Terry Graedon

Alan Greene

Cheryl Greene

John Grohol

Dan Hoch

Jon Lebkowski

John Lester

Danny Sands

And, I should add, Tom’s wife, Meredith Dreiss, who hosted us at their home in Texas as we worked — and mourned — together.